Story by Bob Jones

Arsenic is a lethal poison, but nature uses it to create some very beautiful minerals. We are all familiar with the more important arsenides, like primary arsenopyrite, and secondary arsenates like adamite and legrandite are very well known and frequently discussed. These are the subjects of a later article.

That leaves a large suite of arsenic species that may be less widely known, but certainly eagerly sought by collectors. Others are so uncommon or rare that they do not lend themselves to the collector market.

Uncommon And In Demand

Quite uncommon species that are still well worth describing because they are in demand among collectors are arsenic species like liroconite, clinoclase, olivenite and chalcophyllite, which are very attractive and have been found in well-crystallized specimens.

The mines of Cornwall, England, which produced arsenopyrite as one of their major ores, are well-known sources of these four secondary species. Arsenic, a semimetal, and the metals copper and tin were abundant enough to be mined and processed there.

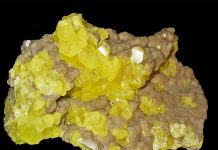

The element arsenic has been recognized for centuries. It was among a small group of native elements long known to the ancients who dabbled in alchemy, the pseudo-science of the Dark Ages. Researchers doubt pure, or native, arsenic was well known in those ancient times, as it has always been a very rare natural element.

What the alchemists called arsenic was more likely common arsenic sulfides, like orpiment and a mineral they called “sandarac”, most likely a form of realgar. It was not until the silver mines in Germany opened around 1000 CE that actual native arsenic was found in several silver mines at Freiberg (Saxony), Joachinsthal (Bohemia), and Andreasberg (Harz Mountains). The common arsenic crystal form was mammillary, though a few crude crystals were found.

Examining Arsenopyrite

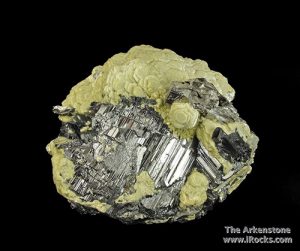

The primary arsenic mineral is arsenopyrite. The finest arsenopyrite crystals found in recent decades are from the Barroca Grande mine, in Panasquiera, Portugal. This is a source of superb silvery arsenopyrite blades associated with fluorapatite and quartz.

These superb crystals began to appear on the collector market in the early 1960s, and for 10 years, they were recognized as the finest arsenopyrite specimens found in quantity. Typically, the Portuguese arsenopyrite crystals are about an inch long, but exceptional blades several inches long were found on rare occasion. Some showed oscillatory striations across the crystal faces.

Arsenopyrite is an iron arsenic sulfide that develops in hydrothermal deposits, and occasionally even in pegmatites. In Panasquiera, arsenopyrite occurs with superb, zoned, purple fluorapatite crystals and black, striated ferberite that can be several inches long.

All these minerals occurred on fine quartz crystals.

Legendary Locales

The Obira mine, on Kyushu Island, Japan, once yielded fine, small, sharp, silvery crystals that were slightly curved, with a rounded termination. Trepca, Yugoslavia, also produced nice, small arsenopyrites before World War I.

Shortly after that, fine Pansquiera arsenopyrite crystals began coming from the El Tajo mine, in Chihuahua, Mexico. The best reached 2 inches in length, and when they came to grass they were a nice silver color, but they quickly turned gray. The arsenopyrite formed in slightly curved, blunt crystals clustered in subparallel arrangement. The Parral, Chihuahua, arsenopyrites were Mexico’s best, though a mine at Zacetcas did yield some larger crystals, but never in quantity.

The mines of Cornwall are best known for tin and copper. The tin was mined beginning some 3,500 years ago, and perhaps even earlier. What the Greeks, Phoenicians and Romans called the Cassiteride Islands were undoubtedly the British Isles. Tin, or cassiterite, was first sought for use in making bronze. Copper, which came a bit later, became a mainstay of the Cornwall mining industry. A lesser-known metal ore was arsenopyrite, but its impact on the mineral suite of Cornwall cannot be overstated!

The mines of England have long since closed, but the suite of secondary minerals arsenopyite produced due to weathering is still eagerly sought. Arsenopyrite was mined and processed into a white powder of nearly pure arsenic. Imagine handling such a product in the 1800s, when gas masks and proper breathing protection had not yet been invented. To help avoid inhaling the white dust, miners stuffed cotton up their nostrils.

You can guess the results!

Cornish Mine Review

The arsenopyrite in the Cornish mines is important not so much as a sulfide, but for the secondary species it fathered. Weathering of Cornish arsenopyrite produced some of the world’s finest examples of liroconite, olivenite, clinoclase and chacophyllite, all secondary arsenic species.

Of these four, liroconite, a fairly complex hydrous hydrate copper aluminum arsenate, is probably the best known. It is a lovely blue color and was found in small, bright crystals lining cavities. Its primary source was Wheal Gorland. (“Wheal” is the Cornish word for “mine”.) It was also found in Wheal Muttrell and Wheal Tin Tang. Though the mines have been closed for decades, there seems to be a reasonable quantity of liroconite extant, as a specimen or two shows up from old collections regularly.

The world’s finest liroconite specimen has been featured in a number of magazine articles and books. It is a sharp, saillike, 2-inch crystal of excellent color, with light striations. It is part of the Philip Rashleigh collection, which resides in the Royal County Museum at Truro. Rashleigh obtained it in 1811. I have had the privilege of handling the specimen in order to photograph it, at the courtesy of my good friend Courtenay Smale, a Royal County Museum board member.

Aside from the Rashleigh collection, one of the most remarkable and historically important collections in Cornwall resides in Caerhays Castle, near St. Austell, on the south coast. Curated by Courtenay Smale, this collection was described in a superb text by Peter Embrey, then-Curator of Mineralogy, British Museum of Natural History, and R.F. Symes, as being “famous throughout the 19th century”. For decades, the Williams family operated upwards of 22 mines in Cornwall and Devon. Throughout two centuries, they assembled an amazing collection numbering in the tens of thousands of specimens.

When the family acquired Caerhays Castle in the mid-1800s, they invited the School of Mines, Camborne, and the British Museum of Natural History to help themselves to specimens, thus reducing the size of the collection to perhaps a thousand specimens. It is safe to say that these two organizations owe some of their finest Cornwall specimens to the generosity of the Williams family.

Superb Species

The Williams family collection holds 20 or so liroconites, a handful of superb clinoclase specimens—including the finest spherical specimen—a suite of fine olivenite crystal specimens, and several breathtaking chalcophyllite specimens. These superb arsenic species are complemented in the collection by England’s finest torbernite crystals, stunning Chessy azurites, a choice pyrargyrite from Guanajuato, Mexico, and dozens of other superb species.

Olivenite from Cornwall develops in tightly clustered needle-shaped, or acicular, crystals lining cavities. These needles are dark green and have an almost velvety shimmer to them. This mineral was found in several Cornish mines, including Wheal Carrharrack, where the original specimens were found. It also came from Wheal Gorland and Wheal Unity, as well as Tavistock, in nearby Devonshire. Both the Rashleigh and Williams collections have several really choice olivenites.

In this country, fine, small olivenite specimens were found by collectors at Gold Hill, Utah, and Majuba Hill, Nevada. In recent years, some fine specimens have come from the famous Tsumeb mine, in Namibia, Africa.

The Tsumeb olivenite specimens were found in several different forms, all of them very fine. It was found as elongate, small, blocky crystals and as tightly clustered, acicular, dark-green needles. Cap Gronne, France, is well known for a range of minerals, mainly micromount crystals. The olivenite crystals from here are elongate prismatic crystals of fine green color.

Rarity and Relation of Clinoclase and Olivenite

Clinoclase was found in some of the same mines as olivenite. It is a copper hydrous

arsenate, while olivenite’s very similar chemistry has one fewer copper atom. This is because they form in the same environment. Both are monoclinic, but clinoclase can be tabular, in crystals that sometimes form pseudohexagonal crystals. Much more common are needles of clinoclase, which develop in tight, radiating groups that form as fans and sometimes in complete spherules. When these radiating spherules are broken, the fan arrangement of the needles is very obvious. The color of clinoclase needle clusters is dark green, but they can be so dark as to appear blue-black.

Some of the most attractive and classic examples of clinoclase are found in the Williams collection, housed at Caerhays Castle. The finest of these is a 3-inch-diameter specimen that developed in a complete, smooth-surfaced spherule of radiating needles. This specimen is generally considered the world’s finest by collectors who know Cornwall species very well.

Of all the secondary arsenic species from Cornwall, the most beautiful is chalcophyllite.

In my opinion, it actually exceeds the complex copper, aluminum arsenate hydrous hydrate liroconite. While liroconite is a lovely blue mineral in well-crystallized prisms, chalcophyllite glistens with a lovely greenish-blue color, and occurs in platy, aggregate, hexagonal crystals in superb micaceous clusters. It flashes with a very attractive pearly luster, which enhances the overall appearance of the small crystals. The crystals are never large—seldom more than a few millimeters across—but clusters of them line cavities in matrix and sparkle beautifully. Their sparkly luster and rich color and attractive crystal clusters really make chalcophyllite one of the more appealing, most attractive copper arsenates found in Cornwall. Some chalcophyllite crystals are quite dull and tend to be a pale, cloudy, greenish-blue color, and have been shown to be altered to chrysocolla.

Appreciating Scarce Minerals

The mines of Cornwall that yielded chalcophyllite include Wheal Gorland and Wheal Unity. These two mines often produced the same suite of species, since they actually exploited the same ore vein, or lode. Wheal Ting Tang, as well as mines in St. Day and Redruth, also produced fine chalcophyllite crystals.

Unfortunately, the arsenic minerals from Cornwall have long since disappeared from the market. Once in a while, a liroconite shows up from an old collection, but they are seldom seen otherwise. The same is true of native arsenic, which showed up sparingly in some of the silver mines of Germany and Czechoslovakia.

Fortunately, small examples of some of the arsenic species have been found at Majuba Hill and Gold Hill, favorite collecting sites for Western collectors. Tsumeb is now closed, so arsenic species from that mine are eagerly sought, but seldom offered for sale.

Author: Bob Jones

Holds the Carnegie Mineralogical Award, is a member of the Rockhound Hall of Fame, and has been writing for Rock & Gem since its inception.

Holds the Carnegie Mineralogical Award, is a member of the Rockhound Hall of Fame, and has been writing for Rock & Gem since its inception.

He lectures about minerals, and has written several books and video scripts.