Story and Photos by Brian Rider

Sometimes, it’s hard to say when a journey begins. I’ve always had an interest in rocks. I would poke around here and there, finding nice pebbles or a little fossil while out in nature, and bought tumbled stones and little crystals from local shops every chance I got. I’ve lived in rural western New York my whole life, and I have always been told that there weren’t any cool rocks or crystals in New York state, except for the Herkimer quartz from the Mohawk River Valley and garnet from the Adirondack Mountains—both places hundreds of miles to the east of my home. I didn’t know anyone who was really into stones, so my inner rockhound was largely hidden and ignored for many years.

Later in life, I discovered the art of lapidary. Around this time, my urge to search was rekindled. I was out looking for wild mushrooms and found myself paying just as much attention to the rocks. The little pretties I would find were not the ordinary shale and limestone that make up the ground in this part of the state. I started to wonder, “What if people are wrong when they say that you can’t find gemstones in New York?” I decided that I would search and see what I could find.

New York’s abundant flora hides rocks, so I focused on surface collecting in gravel pits and waterways. I didn’t know a whole lot about rocks, minerals or fossils, so I had a long way to go. I started going out whenever I could find time and was amazed at how it felt. With only nature and myself, I was able to feel peace. I felt a connection with the stones and knew that I was going to find something amazing. I was going through a very tough time in my life, filled with turmoil and self-doubt. But when I was out rockhounding, it all washed away, and it was just me and the stones.

Being interested in lapidary, I was primarily looking for something of lapidary quality, but it wouldn’t come easily. New York gets a lot of rainfall and has fluctuating seasons, so surface collecting involves looking at a seriously weathered rock and trying to imagine what it looks like inside. This area of western New York was carved out by glaciers that left behind all kinds of glacial dump: severely weathered, gouged and scarred rocks. Luckily for me, I have a good ability to “see into the stone”, so to speak. I was able to look closely enough and see certain characteristics within a rather mundane-looking piece and see the beauty hiding within it. I’m sure most rockhounds would refer to many of these rocks as “leaverite”!

It didn’t happen quickly, but I never lost faith that I would find something amazing. As time went by, I tried to learn all I could about rocks, minerals and fossils, and whenever time and weather allowed I would hunt. In the beginning, I believe even my wife thought I was crazy! My neighbors definitely did. I would come home from a day out with a backpack bursting with rocks and fossils, grinning ear to ear and just waiting to show them off. I would get them wet and show them to my wife, while enthusiastically explaining how cool they were. It didn’t really matter to me if the whole world thought I was crazy—I never lost faith. Over the summer months, I would do my thing, immersing myself in nature’s solitude and the quest to be one with the stone.

A few years had gone by and I’d found some cool rocks. Some even had good lapidary potential, but they just weren’t the one that makes my heart race, my eyes bulge, and my mouth twitch—the one that leaves me breathless. I would know it when I found it, and I knew I would eventually.

This past season felt different right from the start. It would be my third year in a row out looking, and I’ve always liked the number three. I just knew this would be my year. I had recently bought a slab saw and I was looking forward to testing some of my finds. At some point, when I was supposed to be slabbing jasper, I decided to try one of my own finds instead. Previous experiments hadn’t gone as hoped, but I felt optimistic on this day, so I grabbed a piece of fossil hash that I had lying around in my shop and put it on the slab saw.

As the first slab dropped off, I was very happy. It was basically “clam chowder”, which is a lot of brachiopod shells in a generally solid-color sedimentary matrix. The part that made me smile was the little pockets of white, banded agate! Agate may be common elsewhere, but in New York it is scarce, at best. I’ve been able to find small veins of it in chert, but I had never found anything significant.

To say that I was intrigued would be an understatement. I continued to slab off the rest of the small rock, thinking about the pattern of fossil hash. Then I remembered a small piece of fossil hash that I had picked up my first year out. I had just happened to pick up another piece of the same material that was similar, but larger.

Yes, I have a weakness for fossils—the cool ones always end up in my pack even though it’s already way too heavy—but that wasn’t why I had these two rocks. I’d picked them up because they were different. They showed slight reddish and yellowish tinges and, upon close inspection, they showed great detail of the fossils on the outside, despite being very weathered. These rocks were pretty beat up, but I could swear that there appeared to be agate formations around the fossils.

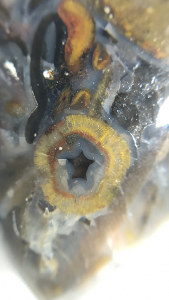

Obviously, another piece of fossil hash was the next rock on the saw. I put the larger one on and waited with anticipation for the end cut to drop off. As I lifted the hood of the saw, grabbed the first cut, and looked at the inside of the stone for the first time, I almost wept. I never would’ve imagined that I could find a stone as absolutely amazing is this. I was staring at brightly colored fossils with intricate details suspended in agate! I knew immediately that this was the one, the stone that I had been searching for. I wiped the cut face free of oil to reveal a very smooth surface, free of pits or fractures, and viable for lapidary use. I could tell it would polish very nicely!

It was a sweet moment when I showed the cut face of that stone to my wife and watched her eyes widen with amazement. I felt proud. I had spent years thinking about it and countless hours hauling rocks on my back in the blistering sun over miles of rough terrain in the pursuit of a truly stunning gemstone from New York. I was looking for something new, something of my own, and I had finally found it. I wouldn’t have thought my stone would be fossil hash, but I just had to learn to take what nature provides.

Soon, I had some designs sketched out on slabs and was ready to start cutting some cabochons. When I started trimming, I knew that this was going to be fun. The slabs cut smoothly, with no fracturing or chipping; the material was hard, but not too hard. When I started grinding and polishing, I was immediately in love. This stone cabs nicely; it grinds smoothly without chipping or fracturing. There are some pockets of softer gray material that cut quicker and can cause issues, but once you know, it isn’t a problem. The pockets are usually surrounded by attractive yellow patterning.

Once I started forming and doming the cabs, it became hard to focus on cutting with all the fresh patterns popping out and drawing me in. I found it absolutely mesmerizing to watch these bright-colored little creatures emerge from the hidden world they’d been trapped in for hundreds of millions of years. Being the first person to witness this world from this particular perspective felt like an honor.

The entire sanding and polishing process went without issue, and I was pleasantly surprised by the overall quality of polish. Some of the fossils take a little less of a polish, as opposed to the mirror polish of the agate, but the result is exceptional, considering the wide variety of material within the stone. That was all I needed to see: In my mind, it was a gemstone.

Every piece is unique, showcasing different fossils or angles of arrangement, and the visual chaos is just mesmerizing. There is also tan agate, and the pockets show great banding and orbs. When the material was polished, it was easy to see that there was a beautiful blue agate base with white agate pockets and fragments peppered everywhere throughout. The agates showed great banding and bots. I believe the yellow and red material is jasper, and there is pyrite sprinkled throughout, as well. There are some minerals replacing fossils that I haven’t identified yet, but I’m working on it.

The fossils contained in this material include bryozoans, corals, brachiopods and crinoids. How they reveal themselves depends on how they fell to the sea floor upon death and how I orientated the stone for cutting. Amazing starburst patterns, tiny, perfect flowers, and streaming multicolor fireworks are just some of the common patterns in this beautiful stone. It’s estimated to be from the Devonian period (417 million to 354 million years ago). When I gaze into this stone, I feel like I’m looking through a window into an ancient world. It almost seems that the fossils will squiggle to life in their beautiful sea of agate.

It didn’t take me long to become obsessed. Every cab I cut, every step of shaping and polishing, revealed something new and wonderful. I had a lot of great lapidary rough lying all around me from all over the world—high-grade stuff, some of which I hadn’t even gotten around to working with. All I wanted to cut were the fossils.

Over the course of cutting the next 80 or so cabs, I thought about a name for my stone. My thoughts kept returning to the idea of ancient life. “Ancient Life agate” seemed fitting for a stone made up of ancient fossils floating in agate. It took me years, blood, sweat and tears, but I had accomplished what I set out to do. I’d found a beautiful gemstone of my own, something new and exciting in New York. I learned a lot along the way. I discovered a connection with nature that I’ll never let go of, and a confidence within myself that will never leave. I don’t know how much ancient life agate is out there or if I’ll ever find it again, but I do know that as soon as the ice melts and the birds start singing, I will be out there with the sun on my back and a smile on my face, looking for nature’s treasures.