By Bruce McKay

When I retired in 2014 from a career as a goldsmith, designer, gem dealer, shop janitor, gemologist and teacher, I decided to expand my lapidary skills and travel the world.

I started doing lapidary work in 1970, but I never was able to cut stone for as many hours as I wanted. I made my living doing one-of-a-kind custom jewelry in gold and platinum, and I cut the occasional cab or inlay for a job but could not afford to take much time from my jewelry bench to play at my lapidary bench. Still, I have cut many cabs, completed quite a bit of inlay work, and I do pretty well around a lapidary shop, or at least I used to think I was good.

Lapidary Travel Itinerary

During a 2015 trip to Idar-Oberstein, Germany I visited the workshop of one of the best agate bowl carvers in the world, Bernd Hartmann, as well as the workshop of two of the best cameo carvers, the father and son team of Dieter and Andreas Roth.

I had decided to shift my lapidary work into larger projects and looking at the work of Dieter and Andreas made it clear that I didn’t have enough years left in my life to become a good cameo carver. So I decided to become a bowl carver, starting with little bowls that I could manage. I do not speak German and there were no opportunities for me to play and get in the way in the shops there, so I began to look for another place to learn.

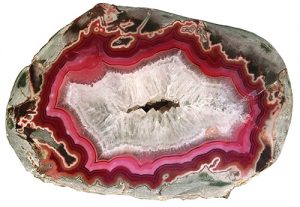

At the 2017 Tucson Gem & Mineral Show, Andreas Roth introduced me to Perry Davis, the president of Gem Artists of North America. I loved his large stone sculptures in agate and jasper, and he had some beautiful bowls carved in agate. Examples of his sculptural work are displayed on his website, www.perrybdavis.com. I told him of my desire to learn how to carve an agate bowl and he invited me to visit his workshop. That was a generous offer I couldn’t refuse, even though it turns out his workshop is in China. At his invitation, between 2017 and 2018, I spent 12 days and one month in his shop.

Studying With Masters

As I arrived for my first visit in 2017 a friend of Perry’s met me at the Beijing Airport, where I would then board a train. He led me to the train and to my sleeper booth, where I had the top bunk in a stack of three. Six hours later I woke up and got off the train in Jinzhou City, located just west of North Korea. This city in is the heart of the agate mining and carving region of China, where artists have been carving agate for hundreds of years.

Perry was waiting for me at the Jinzhou station and we went first to a fruit market for supplies and then off to his workshop. His carving workshop and home are in an enclosed compound with a garden, courtyard, and various dogs. It was a twelve-day gem carving summer camp, with no distractions, other than playing with dogs.

The work produced in this region and gallery is mostly sculptural carvings of agate, jasper, and stony meteorites. Sizes range from 6 to 20 inches in height, and all carvings are mounted on bases with inset bronze pins and sleeves. Each carving is balanced perfectly so it spins effortlessly around for all sides of the sculpture to be seen. Furthermore, the finished polish is always of exacting German quality perfection.

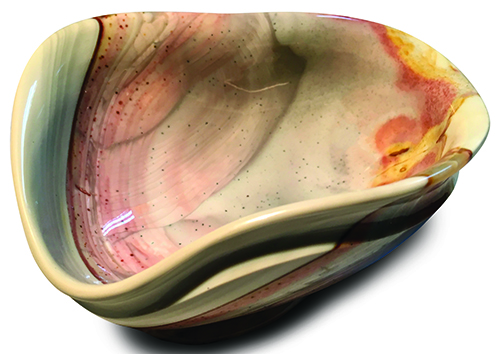

A secondary aspect of the workshop is the creation of agate bowls. Some of these are bowls cut entirely in his workshop and some are cut poorly in other local shops and recut in Perry’s shop, to meet German-quality standards. I bought one of these poorly cut bowls as my practice piece and I brought a rough piece of Idaho Willow Creek Jasper to make into a bowl.

An Exercise in Ancient Practices

The staff working in Perry’s shop includes four gem carvers who have

worked together for more than 45 years. The two men and two women previously worked in a communist-era agate carving factory with 1,000 other cutters. When the factory closed, they were allowed to take home their carving lathes, so each of Perry’s workers works with their lathe.

To start his designs, Perry begins with the rough material and preforms the stone before creating the design that will be produced. He draws the design on the rough with a felt pen then gives it to Zhang for carving. She rough grinds the design, while keeping in constant communication with Perry. As she progresses, he marks an X with a felt pen on the areas needing more grinding and an O on the areas to be left alone.

When large areas need to be cut or a bowl hollowed out, the job goes to Zhang Li. Surface preparation work on carvings or flat surfaces is done by Li Zhao, who also does the final polish work with Cerium Oxide.

During three days, Zhao worked on polishing one piece, which was an agate with stalactite growths. I don’t know how many days he had worked on it before my arrival, but that was my first indication that the projects in this studio required many hours of work, no quick knocking out cabs in this place. There are sculptures here that took over 2,000 hours to create.

I was treated as a fellow carver by Perry and the Chinese artists once they saw I came early each morning and worked beside them all day. They showed great patience with me, never made me feel like the novice in the room. The workers invited me to sit with them at lunch, which is a meal made from food grown in the studio garden. However, the respect shown to me was slightly a hurdle to learning lessons.

Carving and Learning

The artists would show me techniques, which tools to use, and then leave me alone at my carving lathe. I would make mistakes that they would have stopped from happening had they been looking over my shoulder, but I was on my own to learn the hard way. Of the five bowls, I carved or attempted to carve during my two visits, I messed up three, one of them irreparably, and with necessary design changes to save the others.

I had slabbed off the top and bottom of a Willow Creek jasper at home that Perry thought would be a good practice piece. We mapped out where to grind and I went to the main grinding units. The units are 8-inch Poly Arbors with 40 grit and 100 grit diamond wheels. The Poly Arbor is mounted at a 45-degree angle on a steel frame so you can walk up to it and the wheels are chest high. I put on an apron and rubber boots and went to work. Standing with the wheels at a good height I could lean in and grind away to where I wanted the bowl shape to go, while the coolant water sprayed onto my apron, on to the concrete floor, and off to a floor drain.

Next, I brought the Willow Creek bowl to Zhang Li, to be hollowed. Li likes to use three-inch bronze sintered saw blades, which he soft solders onto a shaft and hand trues. The unit is mounted on his lathe along with an overhead water drip. He makes parallel cuts with slabs in between then pops the slabs loose with a steel lever. He also cuts down and gives side pressure to the blade, to free the material he has separated from the mass. He ends up grinding a third of the material and popping loose the rest, a very efficient process.

I tried it and when I attempted to add side pressure on the saw blade I broke the lead solder holding the saw to the shaft, at which point I had to take it back to Li. He resoldered it, trued it and five minutes later I was back to have him reattach the saw. He was a very patient teacher.

After the Willow Creek bowl was ground to the exterior shape I wanted the interior hollowed, so I set it aside to be finished during my second visit.

Hands-On Instruction Humbling

Then, using the agate bowl I had purchased, I learned how to grind it to a thinner state and take a polish. This is when I learned just how little I knew about doing lapidary work at the level of a master artist.

The bowl I created is small, fitting into the palm of my hand. The walls of the bowl overall were 7mm thick, so I ground it down to 3mm, taking it from opaque to a glowing translucence. It took me 30 hours to bring that little bowl to a polish, before giving it to Zhao for the final high polish.

I started my work on this bowl by doing overall surface grinding at the carving lathe. Perry uses locally made diamond grinding wheels, mostly plated rather than sintered. Having a low opinion of plated grinding wheels, I was amazed that none of them showed any wear while in use.

After getting the vessel ground to where it needed to be, I was ready to move to the next step. Next, I took it to Perry, where he pulled out his felt pen and marked it with X’s and O’s and sent me back to the bench.

Do you recall earlier in this article, where I stated that I am a good stonecutter? Many times during my visit, I’d see Perry or someone on his team glance my way and there I would be grinning, sure that I was ready to graduate to the next step. But then, loupes would come out and felt pen markings would send me back. This happened up to six times before I could move forward.

Grinding Process

I took the bowl through the finer and finer grits of diamond wheel grinding, then the various grits of rubberized diamond pads, and on to the grits of diamond paste. Eventually, my bowl was ready for the final Cerium Oxide polish. I gave it to Zhao and he worked on it for an hour, handing it to me just as I left the shop to catch my train. He told me there is a spot on the top edge that needs to be taken back two steps then broug ht back up to final polish. I have proudly shown that bowl to all my friends and family, and I have never taken out a loupe to look for that spot that needs more work.

I went back to Perry’s workshop in November of 2018, to work and learn for a month. I was able to spend lots more time practicing the techniques, plus learning by making mistakes. I finished the Willow Creek jasper bowl, made a bowl with a druzy interior and dendritic covered exterior, and a cute little bowl from Dryhead agate, and destroyed what would have been a fabulous Blue Mountain jasper bowl.

As for the Willow Creek bowl, I chipped it on the top edge while inspecting it. I was trying to locate where the bur was cutting, and not looking where the arbor was about to chip my bowl. To address the chip, I had to recut the top edge design but the recut followed the color pattern of the stone, so my mistake enhanced the design.

I managed to carve the Dryhead agate bowl without making any mistakes. The bowl I was most excited to complete was the druzy interior bowl with little dendrites covering the outside. A natural thin spot had me very worried, but it turned out that my inattention was the greatest threat. I was using a diamond grinding pad that was not generating heat, but also not being aggressive enough to remove the scratches I was chasing. I switched to a pad that turned out to be an effective creator of heat. To gauge heat build-up, I always hold a finger on the inside of the bowl wall directly opposite the grinding or polishing pad.

Well, not always as this time I was holding the sides of the bowl away from the grinding pad and I was not paying any attention to the heat until I heard this loud cracking noise. A crack had resulted in a three-inch smile across the wall of my precious bowl and a larger frown upon my face. Disheartened, I polished the exterior to a 1200 grit surface and left it there, still needing a better polish.

Trip of a Lifetime

The next bowl I worked on was a piece of Blue Mountain jasper. With

this piece, I was going for a perfectly symmetrical shape. I ground the exterior, which showed pink and light green hills all around the bowl with blue sky above. I cut slices into the interior to hollow out the insides and when using the steel lever to pop the attached slabs off, I went after a too thick slab with too much force. I blew off a third of the bowl, destroying it, and teaching myself a lesson I hope I never forget.

Now I have to begin using what I learned in China in my shop. I will miss having such wonderful and experienced carvers around me as I try to always remember what they taught me to do and what I hope I learned to never do again.