Was Anne Brontë a rock collector? Yes! Evidence now suggests she was an informed and skilled participant in the emerging science of geology just as it entered its ‘golden age.’

About Anne Brontë

No one would have accused Anne Brontë of being pliable. She was the youngest, after Charlotte and Emily, of the 19th-century English sibling creators of Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey. Anne had a strong voice, and even stronger viewpoints, as an author and woman before tuberculosis claimed her life just shy of her 30th birthday in 1849.

Now the University of Aberdeen in Scotland and student Sally Jaspars have brought renewed attention to Anne Brontë and an astute collection of agates, carnelians, flowstone and red obsidian.

In 2022, Jaspars (no geologic pun intended), a student at the University of Aberdeen’s Department of English, was studying Brontë when she kept noting the writer’s references to books by well-known scientific and geologic authors, including in her most controversial work, The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall. Written under the pseudonym, Acton Bell, Brontë’s depiction of alcoholism, adultery and domestic abuse were considered unwholesome topics for women authors.

Description & Identification of a Collection

“Anne’s interest in geology is in her literary works,” Jaspars said. “The Tenant of Wildfell Hall directly references the science and a book by Sir Humphry Davy (who used electrolysis to identify the elements barium, calcium, magnesium, and strontium). She was an intelligent and progressive individual in tune with the scientific inquiry of the time. This is the first time that Anne’s collection has been systematically described and fully identified and, in doing so, we add to the body of knowledge on Anne and show her to be scientifically-minded and engaging with geology.”

Jaspars contacted Dr. Bowden from the University’s School of Geoscience for assistance in analyzing the collection at the Brontë Parsonage Museum. For the first time, the Anne Brontë rock collection underwent complete description and identification, and along with Professor Hazel Hutchison of Leeds University and Dr. Enrique Lozano Diz at ELODIZ (a company specializing in spectroscopy analysis), an analysis of that collaboration, Anne Brontë and Geology: A Study of her Collection of Stones, was published in April 2022 in Volume 47, Issue 2 of the peer-reviewed journal, Brontë Studies & Gazette.

Portrait of Anne by her sister Charlotte. Courtesy the Brontë Society

Raman Revelations

“Anne Brontë did not just collect pretty stones at random but skillfully accumulated a meaningful collection of semi-precious stones and geological curiosities,” said Stephen A. Bowden, with the University of Aberdeen School of Geosciences and co-author with Jaspars on Anne Brontë and Geology, explaining how Raman spectroscopy analysis revealed a “meaningful collection, sufficiently unusual and scarce, to show they were collected deliberately for their geologic value.”

Raman quartz spectrography, whose 1928 discovery made physicist C.V. Raman the first Asian to receive a Nobel Prize in any branch of science, is a non-destructive analysis technique using scattered light to measure vibrational energy modes, whereas, conventional spectroscopy uses differences in wavelengths from emitted, transmitted or reflected light to provide higher and more specific degrees of clarity. Geologists use Raman spectroscopy to gather data on minerals that cannot be identified by eye or microscope, and since the stones in this collection were mostly cryptocrystalline, their mineral components (grains or crystals) were also unidentifiable by visual or optical means.

Not a Casual Collector

So it was going to be Raman on the menu. Did the twenty-something Anne, working as an unhappy governess in Scarborough, simply beach-comb what pleased her without ascribing much geologic merit to her choices? Bowden continued, “We applied Raman spectroscopy to Anne’s stones and identified their mineral composition which, in combination with the Geological Hand Specimen Description, provided a fuller perspective on their nature and thus significance by providing information that could not be obtained from visual inspection alone.”

What they discovered was no casual collection by a bored babysitter. In addition to carnelians and agates, they identified flowstone and red obsidian not found within the United Kingdom.

“Our Raman spectroscopy analysis, which we undertook at the Brontë Parsonage Museum, shows that she did not just collect at random. Anne’s collection comprises stones sufficiently unusual to show they were collected for geologic value. Her collection took skill to recognize and collect,” he said.

Wikipedia/Creative Commons

Anne Brontë’s Stones

Anne Brontë’s stories and connections to mineralogy and geology reveal her interest, knowledge and abilities within these fields. Working across literature, history, and science, this renewed research has refined our perception of her as a more fully formed and well-informed individual who engaged in scientific activity.

Much of the collection consists of small rounded carnelians, less than half an inch across and ranging from pale orange to dark red, but three more angular red stones have — for the first time — been identified as mahogany obsidian.

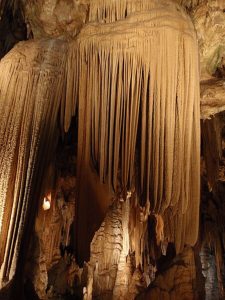

Anne Brontë – Flowstone

Also for the first time, a larger stone has been identified as speleothem flowstone or “frozen waterfall,” a kind of calcium carbonate that forms, like stalagmites or stalactites, inside of caves. Her piece has no growth rings or banding, but it does have a rind on its exterior and ribbon-like folds terminating at each end in artificially cut surfaces. Since calcite is softer than steel, cutting or sectioning this was achievable, the analysts believe, with tools used during Brontë’s time.

The flowstone may have been purchased from one of a half-dozen lapidary shops operating in Scarborough while she was a governess, or it could have been a souvenir from her sister. A postcard by a family friend, Ellen Nussey, announced how she and Charlotte were “very much pleased with going through the caverns” of Castleton and Peak Cavern in July 1845.

Anne Brontë – Agates

Anne also had three large agates, a small white agate with concentric orange banding, and larger quartz-rich pebbles classifiable as carnelians or jaspers. Some of the agates have been broken and show a haggled or uneven surface; some have been cut and reveal a polished surface with a high level of finish.

“This is a non-trivial process,” cited Bowen, “and whoever cut and polished the agates would have possessed specialized skills, knowledge and tools.”

Under this closer scrutiny, the most noteworthy stones have proven to be her flowstone and agates. The researchers noted, “The flowstone has two cut surfaces, implying that it has counterpart pieces that might be physically matched by comparing the cross-sectional areas and flow patterns on the exterior.

“The agates, too, where cut and polished, reveal an internal banding that might also be matched to counterpart pieces. A final distinctive feature of one agate is an internal tube. The tube gives the impression of being biological, such as a spicule, suggesting the fossilized skeleton of a sponge.”

Soft Words For Stones“If you would have your son to walk honorably through the world, you must not attempt to clear the stones from his path, but teach him to walk firmly over them. Not insist upon leading him by the hand, but let him learn to go alone.” – Anne Brontë (1848) |

Anne Brontë: Ahead of Her Time

We can’t know why Anne Brontë chose the stones she did but thanks to Jaspar’s diligence, we can see how her familiarity with geology was woven into her writing. When The Tenant of Wildfell Hall came out in 1847, Brontë used its narrator, Gilbert Markham, to present how both genders should find equal intellectual footing in the arts and sciences.

“So we talked about painting, poetry, and music, theology, geology and philosophy,” Gilbert says on page 73 about his love interest, Helen, before buying a copy of Sir Walter Scott’s Marmion and mentioning the “reliques of snakes […] still found in the rocks […] Ammonitae.”

A Manuscript of Scientific Ideas

The same year as Tenant, Brontë produced a manuscript of scientific ideas, including on the origins of the earth, inspired by the scientist she referenced in Tenant: “Let us take Sir Humphry Davy’s theory found in his Last days of a Philosopher: I know not any more sensible or philosophical view of the geological history of the earliest stages of the world we inhabit!”

“On review,” conclude the authors of Anne Brontë and Geology, “Anne’s collection can be seen to comprise stones sufficiently unusual and scarce to lead us to theorize that their accumulation could result only from deliberate decision. They do not belong to a range of stones one would likely encounter while gardening or walking, for example.

“Furthermore, while all but the mahogany obsidian can be obtained from geological sites in Yorkshire, there is no single geological locality that would yield all the rock types one might encounter in a single visit. Thus multiple visits to multiple localities would be required, either by Anne or by someone else to bring this collection together.”

“Anne Brontë,” surmises Robert Turbyne, deputy head of communications for the University of Aberdeen, with a smile, “was a rock star.”

Smart, talented, and full-throated in her expectation of equity in scientific inquiry, history will remember Anne Brontë as the sister with the stones.

Anne Anew“I think any attention on Anne Brontë is great. She’s been sidelined for a long time,” says Bronte Parsonage Museum curator Sarah Laycock. “It’s fascinating that she had an interest in rock collecting but given the Brontë family interest in the natural world, it’s not surprising. “I’m not sure what Anne would think of the attention. She’d probably think it was quite strange!” |

This article about Anne Brontë and her rock collection previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Story by L.A Sokolowski. Click here to subscribe.