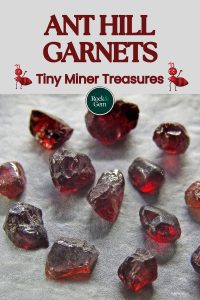

Ever heard of ant hill garnets? You know that old saying about one man’s trash? These small, reddish-brown crystals fall under this adage but with one change to say, “One ant’s trash…” Found in the mounds of harvester ants, these garnets are fascinating gemstones that have been collected and admired for hundreds of years.

What Are Ant Hill Garnets?

Ant hill garnets, also called Arizona rubies, are typically chromium pyrope garnets. One of six main types of garnet, these are the deep red color that most people think of when picturing a garnet. The word pyrope comes from the Greek pyr and ops which mean “fire eye.”

FYI – Almandine garnets can also be found around ant hills. The difference between pyrope and almandine is in the dominant mineral they contain. Almandine is iron (Fe) dominant and pyrope is magnesium (Mg) dominant.

Ant hill garnets are typically small, ranging in size from a grain of sand to a pea. They are often rough and irregularly shaped. Ant hill garnets rank between 6.5 and 7.5 on the Mohs Scale of Hardness, making them strong enough to be worn every day. These brilliant gems are small but mighty!

Garnet Ants

Ants have sometimes been called the world’s oldest prospecting tool. These tiny miners give us a glimpse into what’s beneath the surface.

As the ants dig and move the soil to create their nests and tunnel systems, they take their “trash” to the surface and form a pebbly mound. The pebbles used to build the mounds are usually around the same size. This mound isn’t just a dumping area. It has a purpose as it protects the main nest from wind and rain and holds in moisture. These mounds often face southeast to take in the morning sun.

Harvester ants can be found around the world, and they aren’t picky with what they throw out. Depending on their location, mounds can contain gemstones such as garnets, peridot, diamonds, turquoise and precious metals like copper and gold. They can also contain fossils and animal bones.

Over time, rain and wind erode the pile of pebbles, leaving only the harder and more durable garnets behind. The ants continue to add to this pile of discarded stones, and eventually, a concentration of garnets builds up around the ant hill.

This is where rockhounds and gem collectors come in. Savvy prospectors know to look for these ant mounds and to search the “ant yard” around the nest, carefully sifting through the debris to find ant hill garnets. They also know that the ants are most active in the spring or summer months, so searching in the fall and winter is the better bet. FYI – Fossil collectors also like to search these ant hills and have been successful in finding ancient treasures.

Where Are Ant Hill Garnets Found?

Anthill garnets are found in the American Southwest, mostly in the four corners region in Arizona and New Mexico. These areas have the ideal dry and sandy conditions that are preferred by harvester ants. Many are harvested on the Navajo grounds in this area. For generations, the Navajo people have valued these unique gemstones. They are incorporated into Navajo jewelry and crafts, used in healing practices, and woven into their rich oral tradition.

While ant hill garnets can be discovered in some other parts of the world where similar conditions exist, the southwestern regions of the U.S. remain the primary and most well-known source.

Once the garnets are collected, lapidaries cut and polish them for jewelry such as rings and earrings. Their background makes a fun story when people notice such pretty jewelry. It’s not every day you hear someone say their gems were harvested by ants!

Awareness & Conservation

While ant hill garnets are a fascinating glimpse into nature, it is essential to balance appreciation with a commitment to conservation. Ethical practices in collecting these gemstones ensure that active ant hills are not disturbed.

This story about ant-hill garnets previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Pam Freeman.