Making fine aquamarine jewelry has been a passion for Mark Krivanek of Salida, Colorado, for 25 years. He literally pursues his passion from start to finish, first by mining his own aquamarine and faceting the best blue gems, then by designing, fabricating and retailing his own distinctive line of aquamarine jewelry.

It is not unusual for youthful interests in rocks and minerals to lead to careers in geology, gemstone mining, gemology, or the jewelry trade. But in Mark’s case, it led to all four. A rockhound by age ten, Mark is today a degreed geologist, graduate gemologist, master faceter, jewelry-shop owner and miner who works his own claims on Colorado’s legendary Mount Antero.

Rockhound to Gem Cutter

While growing up in Oklahoma, Mark acquired his parents’ interest in minerals and gemstones. As a sixth-grader, Mark was already visiting rock shops, going on field trips, and reading field-collecting guides. His most memorable birthday gift as a teenager was a subscription to The Mineralogical Record.

Family vacations often focused on collecting minerals, exploring ghost towns and visiting old mines. Mark remembers gathering twinned selenite crystals at Oklahoma’s Great Salt Plains State Park and searching for gemstones in North Carolina where, at age 14, he found an eight-carat ruby. On his first visit to Colorado’s Mount Antero in 1977, he found a 40-carat, terminated prism of gemmy, deep-blue aquamarine.

On a family vacation in Montana, Mark panned for sapphires and was fascinated watching gem cutters at work. Upon returning home, he bought a used ULTRA TEC™ faceting machine and learned to cut gems. And at age 16, he won a master’s trophy in a gem-cutting competition.

Diamond Buyer to Aquamarine Jewelery

Mark initially majored in mechanical engineering at Oklahoma University. “But when a basic geology course really caught my interest,” he recalls, “I switched my major and never looked back.” Mark continued to cut gems, joined the American Gem Society and learned the fundamentals of jewelry repair while working part-time with a jeweler. When he next visited Mount Antero, it was as the leader of a university field trip.

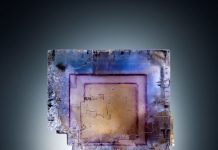

Mark graduated in 1985 with a bachelor’s degree in nonmetal economic geology. After earning certificates in diamonds and colored gems at California’s Gemological Institute of America, he worked with a Denver gem company buying and grading diamonds and often visited the Israeli Diamond Exchange in Tel Aviv.

“Diamond buying was a real challenge,” Mark recalls. “My job was to acquire the high quality and substantial quantity of diamonds that the company demanded without overrunning my three-million-dollar annual budget.”

Krivanek Jewelers

After settling in Salida, a south-central Colorado town in the shadow of Mount Antero, Mark opened a retail jewelry shop. In 1992, he moved the business—now Krivanek Jewelers—to its present downtown location in a historic, 1882 brick building. Today, Mark retails a full line of jewelry, repurposes and repairs jewelry, identifies and appraises gems, and creates his own line of Mount Antero aquamarine jewelry. He also buys mineral specimens, rough gemstones, mining artifacts, old gold and silver and heirloom jewelry.

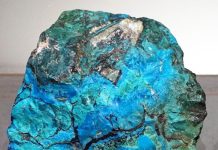

Krivanek Jewelers is a mini museum that showcases mining artifacts and specimens of such Colorado gemstones as Mount Antero aquamarine and smoky quartz, Cripple Creek turquoise, Sweet Home mine rhodochrosite, Brown Derby Mine tourmaline and lepidolite, Ruby Mountain spessartine and topaz, and Crystal Peak amazonite and topaz.

With its nearby old mines, gold-bearing streams and gemstone localities, Salida attracts many rockhounds, gold panners, and weekend prospectors who often bring their finds to Krivanek Jewelers for identification. Mark offers this service without charge to encourage interest in mineral collecting. “I never know what folks will bring in,” Mark says. “A family once asked me to identify a bucket of mine-dump ore specimens. Most of it was pyrite and iron-stained quartz, but the biggest piece was a real surprise—it was flecked with visible gold. We negotiated a price, and I bought it to show my customers what lode gold actually looks like.”

Mount Antero: A HistoryAfter discovering aquamarine high on Mount Antero in 1881, prospector Nelson Wanamaker began selling crystals to collectors and museums. Working from a base camp cabin at the timberline elevation of 11,000 feet and a stone shelter just below the summit, he spent his summers collecting gemstones. Wanamaker faced the same difficult conditions on Antero that confront miners today—a brief, eight-week-long summer mining season; steep, rugged talus slopes; thin alpine air; and the high winds and lightning of summer thunderstorms. Wanamaker also faced the added challenge of working manually, using only the picks, shovels, hammers and bars that he packed up the mountain. During the 1930s, such legendary collectors as Arthur Montgomery and Edwin Over recovered many fine aquamarine specimens that are now in prestigious private and museum collections. In the early 1950s, when beryl was the sole source of the beryllium needed for growing nuclear and specialty-alloy uses, prospectors bladed a rough jeep road up the mountain. But the veins and pockets proved too erratic for commercial beryl mining. With the jeep trail improving accessibility, interest in Mount Antero’s gemstones grew. Several recent, well-publicized aquamarine finds, along with the 2013- 2016 “Prospectors” television series that focused largely on Antero aquamarine, have raised collecting interest to an all-time high. Today, most of the mountain’s pegmatite zone is claimed. |

The Chip ‘N’ Dale Claim

Despite the demands of running a full-time jewelry business, Mark never lost his interest in Mount Antero. This 14,262-foot-high mountain, just ten air miles from Salida, is North America’s highest gemstone locality and premier source of aquamarine. Above the elevation of 12,300 feet, Antero’s granite bedrock is laced with pegmatite veins and pockets containing gemstone crystals, mostly those of aquamarine and smoky quartz.

In 1997, a prospector showed Mark four gemmy, 100-carat aquamarine crystals he had found in an Antero pegmatite pocket. Impressed with their quality and color, Mark grubstaked him to do more exploration— which paid off in additional recoveries. Together in 1998, they staked the Chip ‘n’ Dale Claim on Mount White, the southern part of the Antero massif.

After Mark later became the sole owner, he realized that working the claim seriously—which involved the difficult and often dangerous job of moving huge talus boulders—required mechanical equipment and an experienced partner. Mark found that partner in Lowell Hicks, a longtime Creede, Colorado, hard rock miner. For equipment, they chose a 20-ton, diesel-powered, trackmounted excavator with an articulated boom-arm. Moving this excavator from the nearest county road to the claim—a six-mile journey with a 5,000-foot vertical climb— takes an entire day.

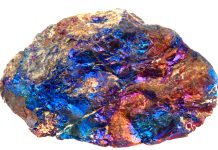

The Appeal Of AquamarineAquamarine is the blue gem variety of beryl (beryllium aluminum silicate). Its name stems from the Latin aqua marina meaning “seawater” which alludes to its similar color. Crystallizing in the hexagonal system as well-developed, six-sided, transparent-to-translucent prisms, aquamarine has a vitreous luster and a substantial Mohs hardness of 7.5-8.0. It occurs primarily in granite pegmatites. Much aquamarine lore is linked to the sea, including the belief that it protected sailors on their voyages. Modern metaphysical practitioners believe that aquamarine provides foresight and courage, enhances happiness and intelligence, and alleviates anxiety-related stress. Transparent aquamarine jewelry is usually faceted into square, rectangular and round gems of one to 10 carats; translucent forms are cut into cabochons and beads. Aquamarine’s color is unique among gemstones. Unlike the cold, pure, ice-like blue of irradiated topaz, aquamarine jewelry always exhibits a subtle hint of green that imparts such appealing qualities as softness, warmth, complexity and depth. Many consumers prefer aquamarine jewelry with gems set in white-metal mounts of silver, platinum or white gold. Despite that popular preference, Mark Krivanek believes that white metal detracts from aquamarine’s clean, cool color. “I prefer yellow-gold settings because they contrast with, and enhance the stone’s blue color,” he explains. In recent years, aquamarine jewelry buyers have focused more attention on domestic gemstones. “That’s because foreign gemstones are often mined in unregulated and unacceptable social and economic conditions,” Mark points out. “And consumers are seeking stones that have been responsibly mined, and that includes Mount Antero aquamarine.” Consumers are also moving more toward natural gemstones, even those with occasional flaws. “Many gems worn today are flawless synthetics,” Mark explains. “But because synthetic aquamarine jewelry is not available commercially, you know that every aquamarine you see is natural. I like to think of Mount Antero aquamarine as a small, natural piece of Colorado real estate.” |

The California Mine

In 2014, Mark and Lowell acquired the California Mine, Mount Antero’s only underground mine. At an elevation of 12,500 feet, this 52-acre patented claim includes most of the California Vein, a mineralized vein that is intermittently exposed on the surface for nearly a mile. The mine is a 220-foot-long drift that follows the vein underground. As wide as three feet, the vein consists of quartz carrying significant amounts of molybdenite (molybdenum disulfide), muscovite and beryl.

The molybdenite appears as coarse, silvery-gray crystals and flakes with a bright, metallic luster. The beryl, which is opaque to translucent and ranges in hue from colorless to blue, includes gem-quality aquamarine. Also present are canary-yellow coatings of molybdite (molybdenum oxide) and brannerite, a complex uranium oxide.

The California vein attracted little interest until World War I when molybdenum was needed to toughen alloyed steel for weaponry. Encouraged by soaring molybdenum prices, miners explored the vein by hand-steeling and blasting a narrow drift. The mine then remained idle until Mark and Lowell acquired the property and reopened and stabilized the portal. Today, in compliance with state and federal underground mine safety requirements, they continue to explore the vein while recovering gem aquamarine.

A Personal Perspective on Gems

Mark’s perspective on gems reflects his collective experience as a geologist, gemologist, jeweler and miner. “I look at gems beyond their obvious virtues of beauty and value,” he explains. “I consider such aspects as their geology, mineralogy, occurrence, sources and mining. All these factors together give every gem and gemstone a unique identity that makes it more interesting, meaningful and exciting—an idea that many of my customers understand and appreciate.

“Gemstone mining, especially mining aquamarine on Antero, is always an exciting adventure,” Mark says. “But the real excitement is not what we’ve already found, but in what we might find beneath that next talus boulder—and Antero has a lot of aquamarine left to find.”

For more information on Mount Antero aquamarine, visit www.krivanekjewelers.net.

This story about aquamarine jewelry maker, Mark Krivanek previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Steve Voynick.