Arsenic throughout much of history has been used as a human poison and inexorably linked with death.

From medieval times through the mid-1800s, members of Europe’s ruling classes frequently used arsenic to dispose of one another. Fittingly, arsenic became known as both the “king of poisons” and, wryly, the “poison of kings.” In France, arsenic was called “inheritance powder,” alluding to its frequent use by impatient heirs to accelerate the demise of family members.

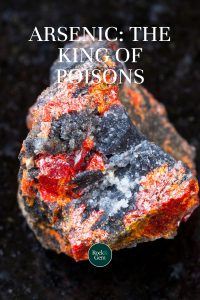

But there is more to arsenic than a sinister image. Specimens of arsenic’s two most familiar minerals, realgar and orpiment, are widely collected for their crystalline beauty and bright colors. In powdered form, these same minerals have been used in medicine and as pigments in the celebrated paintings of many European masters.

The Metal & It’s Minerals

Elemental arsenic is dark gray, brittle, and a poor conductor of electricity. As a semimetal, it exhibits both metallic and nonmetallic properties. Ranking 55th in crustal abundance, it is about as common as tin. Although occasionally found free in nature, most arsenic is a component of more than 250 minerals, the most abundant being arsenopyrite (iron arsenic sulfide), which forms opaque, prismatic crystals with a steel gray color and metallic luster.

Next in abundance are red realgar and yellow-orange orpiment. Both these arsenic sulfides crystallize in the monoclinic system; occur in close association, and share similar properties.

Medicine and the Arts

By 3000 B.C., the Chinese were using realgar and orpiment as pigments and as sources of elemental arsenic, the latter to make crude, bronze-like, copper alloys. Although aware of its toxicity, Chinese physicians learned that arsenic also had therapeutic value when administered in small doses. By 1400 B.C., realgar and orpiment were standard pharmaceuticals in Chinese medicine and were used to treat a variety of ailments.

Drinking rice wine mixed with finely powdered realgar was a Chinese festival tradition. After the wine was consumed in ceremonial toasting, the realgar residue served as a paint to decorate children’s faces—a practice that survives today in parts of rural China.

In Elizabethan England, arsenic-based salves were widely used to clear and whiten women’s skin. Similar salves were used in the United States in the 1800s, as were certain arsenic-bearing compounds to effectively treat syphilis and related bacterial infections.

In European Renaissance and post-Renaissance art, powdered realgar and orpiment were the pigments of many red and orange paints. Unfortunately, centuries of slow chemical oxidation have caused the original, bright-red, realgar-based paints in many works of art to fade.

Arsenic: The “King of Poisons”

Arsenic’s legendary toxicity is because of its chemical affinity for phosphorus, an element vital to all animal and plant cellular metabolism. Arsenic readily substitutes for phosphorus in cellular compounds and even tiny amounts can disrupt metabolism. For an adult human, the lethal dose of most inorganic arsenic compounds is about one-third of a gram, or a volume about the size of a grain of rice.

For many centuries, arsenic trioxide, or “white arsenic,” was the ideal poison. A crystalline solid resembling granulated sugar, it is easily prepared by heating or calcining powdered realgar or orpiment. It is tasteless, odorless, lethal in just several days, and until relatively recently, undetectable in the tissue of the deceased. And the symptoms of arsenic poisoning mimic those of cholera, an extremely common affliction in centuries past.

Arsenic’s use as a poison was first documented in Greece in the 4th century B.C. Historians believe that the Roman emperor Nero used arsenic to eliminate his 13-year-old stepbrother and potential rival, Britannicus. As a broad-spectrum poison, arsenic is toxic to virtually all life forms and has been utilized most extensively to control vermin. Powdered realgar and orpiment, mixed with honey and other edibles and used by the ton, were for centuries the standard rat poisons throughout Europe.

Arsenic Today

In 1836, British chemist James Marsh developed a method to detect minute traces of arsenic in poisoning victims, opening the door to modern forensic toxicology. After courts accepted “Marsh test” results as evidence in murder cases, the frequency of arsenic poisonings declined noticeably.

Arsenic’s macabre notoriety has been celebrated in literature. In French novelist Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, the title character obtains arsenic under the pretense of needing rat poison but instead uses it to commit suicide. And in her long line of murder-by-poison mysteries, British novelist Agatha Christie, herself versed in pharmacology, used arsenic to kill off 30 of her characters.

Despite many current governmental restrictions on the use of, and exposure to, arsenic, the “king of poisons” remains an important industrial commodity. Arsenic is no longer mined, but obtained as a by-product of base-metal smelting. Some 51,000 tons of arsenic trioxide are produced worldwide each year, mainly for use in wood preservatives and pesticides. Ancient Chinese physicians would perhaps be pleased to know that, while arsenic is a known carcinogen, it has been somewhat paradoxically approved for use in the United States to treat certain types of cancer.

Despite arsenic’s sinister reputation, specimens of bright-red realgar and orange-yellow orpiment, are widely collected. Collecting is safe—if common-sense precautions are taken: Always wash hands thoroughly after handling any arsenic-bearing mineral, never ingest particles or inhale dust from these specimens, and store them out of reach of children and pets. After all, arsenic will always be the “king of poisons.”

This story about arsenic previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Steve Voynick.