By Bob Rush

In the past few months, I have acquired some rough pieces of Black Turkish Stick agate. Their outward black appearance is unremarkable and not indicative of what might be lurking inside. The first piece I had acquired had a cut surface that the dealer made to determine what potential the stone had. It didn’t show much promise, so I got it at a discount, though it was still a bit pricey at $40 for the 1-pound piece.

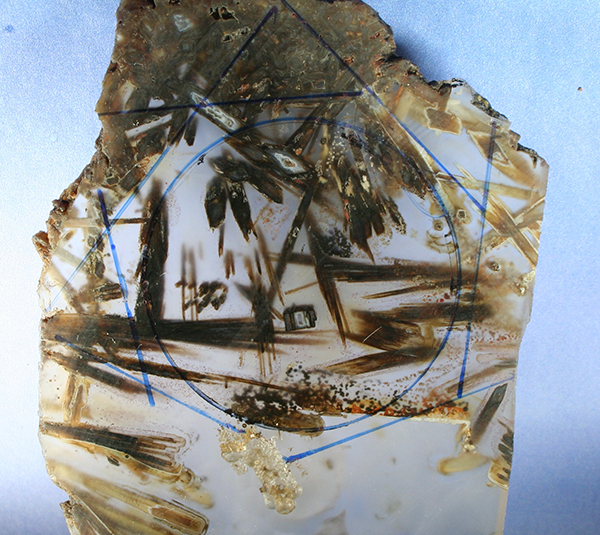

The material was new to me, so in the beginning, I didn’t know what to look for when deciding which way to orient the piece for the first and subsequent cuts to get the best patterns. I looked for any hint on the surface, and there were a few sticklike features on some sides, but not a high concentration of them. I chose one piece with the best images of the sticks and cut parallel to it.

The first slab after the end cut was made with the typical thickness of about 0.187 inch (4.77 mm), and though some stick patterns were visible, it was too dense to get a good pattern. Next, I tried cutting a slab that was 0.125 inch (3.15 mm) thick. It got better results in showing the stick patterns, but it needed to be backlit to see the pattern well. I kept cutting the slabs thinner and thinner until I was at 0.05 inch (1.25 mm) thick, and the results were rather striking.

This is about as thin as this material could be cut and still be a working slab of material. Slabs much thinner than 0.125 inch thick will have to be laminated to some other material to ensure that it is durable enough for cutting into a cab and mounting into jewelry.

I finally ended up selecting a slab that was .10 inch (2.75 mm) thick that had some unique and fascinating stick images. An image of the letter “A” stood out from the rest of the sticks. I made this the center of my cab. I laminated a lab-grown quartz crystal slice of similar thickness to the top of the thin slab to make a doublet. I contemplated also laminating a piece of white agate behind the Turkish agate, but for this project I decided to leave it at a doublet. I cabbed the doublet using the standard cab-making steps, taking the precaution of being very careful not to overheat the top quartz layer. This material is very prone to heat stress fracturing.

Bob Rush has worked in lapidary since 1958 and metal work and jewelry since 1972. He teaches at clubs and at Camp Paradise. Contact him at rocksbob@sbcglobal.net.

Want to receive Rock & Gem magazine in your mailbox or inbox? Subscribe today!