Editor’s Note: This feature by Eugene Mueller, founder and co-owner of The Gem Shop in Cedarburg, Wisconsin, first appeared in Rock & Gem in March 2008.

Editor’s Note: This feature by Eugene Mueller, founder and co-owner of The Gem Shop in Cedarburg, Wisconsin, first appeared in Rock & Gem in March 2008.

By Eugene Mueller

The northwestern United States is rich in collectible jaspers. Major rock collections — both private and in museums — will often have fine examples of Bruneau jasper from Idaho or Morrison Ranch jasper from Oregon.

These jaspers are popular with lapidaries and collectors alike for their fine consistency, intricate patterns, and ease of workability. They also share a formational characteristic, a unique visual pattern not seen in agates. The jaspers that share this pattern are considered by most to be the best of all jaspers.

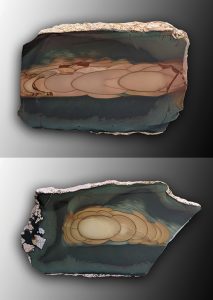

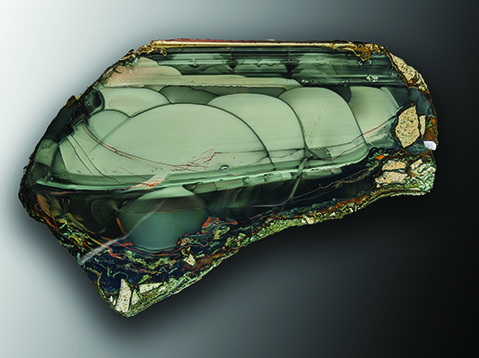

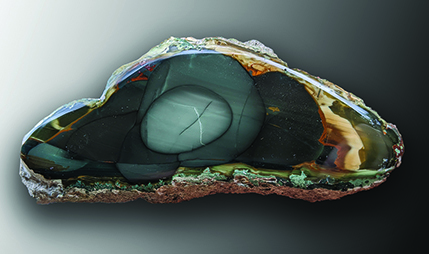

The Bruneau jasper pattern is characterized by a series of overlapping oval shapes arranged in a circular format. An edge or line curves back on itself until it intersects with another line. This element gives the appearance of an oval shape behind the curved line that it crosses. The overlapping oval shapes are an illusion resulting from the repetition of the curved edge. Inside each resulting shape, the jasper changes gradually in hue and value, creating a visual sense of surface. This illusion of visual depth contributes significantly to the beauty of the generally opaque jasper material.

It is important to point out that these shapes are not concentric like the bands in a nodular banded agate but are part of one continuous formation through the rock. Unlike the concentric “shells,” one inside the other, that characterize the bands in a banded nodular agate, the edges that form the receding oval shapes in these jaspers are part of one continuous edge through the rock. If you can imagine moving three-dimensionally through a piece of Bruneau-pattern jasper, it is possible to go from the center of the rock to the outside and never cross one of the visual lines or edges.

If the form could be visualized in three dimensions, it would look something like a soft pillow folded over on itself many times. This form is evident in other natural events. If you pour a very heavy fluid-like thick honey or oil onto a surface, it folds over itself as it lands. The liquid’s surface tension holds the form for only a short time before the liquid becomes homogeneous again. Another example is melted candle wax running down the side of a candle. As the wax cools and solidifies in an oval drip shape, more melted wax flows over it and hardens on the top. This process results in the same type of forms as in Bruneau jasper. If you cut through the solidified wax, you will see the same curved edges that form the overlapping shapes. These edges are the continuous boundary between the liquid wax and the solid wax as it solidifies.

The pattern resulting from this form, so well known in the famous Bruneau jasper, does not have a generally accepted name. Various names are used among Morrison Ranch jasper, or morrisonite is found in Oregon on the east slope of the 2,000-foot-deep Owyhee River Canyon, located a few miles south of the beginning of the Owyhee Reservoir.

Accounts of Discovery

Jasper was detected in this locality in the 1940s when rancher Jim Morrison (no relation to The Doors’ lead singer) invited friends to his cabin on the Owyhee River to go goose hunting. Morrison collected rocks and Indian artifacts on his ranch in the canyon and would show them to anyone who expressed the slightest interest. Back then, the 27-mile trek to Morrson’s cabin took a whole day. Today, it is a two-and-a-half-hour drive on a dirt road to the canyon rim. The first mineral claim here was filed in 1964, and there are currently five adjoining claims. Mining with equipment did not start here until the early 1970s. Between the late 1970s and 1986, no mining took place, but then it resumed for 10 years. No new commercial production has occurred since 1996.

Willow Creek jasper is mined in a small canyon northeast of Eagle, Idaho. Many miners have worked in the area — a thunderegg deposit — where eggs exist next to perlite. A thunderegg two feet in diameter from this deposit is considered small. It takes considerable effort to remove a three-foot-diameter egg weighing several hundred pounds by hand. Unfortunately, not all eggs have jasper interiors; therefore, many such efforts went without reward. I witnessed a mining operation in the late 1980s when mining was done with a D-8’ dozer and an excavator with a hydraulic ram. The dozer would push out the eggs, and the hydraulic ram would open them up. Sometimes, eight to 10 thundereggs in a row would contain nothing suitable, but when a good one was found, the miners made a sudden acquisition of 100 to 200 pounds of excellent jasper.

In the 1980s, there were several claims with different owners. In the early 2000s, Larry Ridly of Boise, Idaho, owned the entire area, which was mined steadily with equipment for two or so decades.

Blue Mountain jasper is found in Oregon, on the south end of the Blue Mountains, just a few miles north of McDermitt, Nevada. This jasper has color combinations similar to those of the morrisonite found about 80 miles to the north. While morrisonite is formed in veins, the Blue Mountain jasper is more nodular in shape, even though the two types are formed in similar rock. Leonard Kapcinsky put the deposit under claim in 1967, and he still has two claims in the area. The deposit worked a couple of times, but no new material has been mined for over 30 years.

The last type is Imperial jasper or a sub-variety known as Royal Imperial jasper. Imperial jasper is found on the east slope of a steep canyon covered with vegetation north of San Cristobal, Mexico. It is also found in a smaller drainage to the east of the main canyon. Many deposits are found in the area, each one with a little different character. Red Imperial, Pink Imperial, Brown Imperial, Green Imperial, Spider-web Imperial, Select Imperial, and Royal Imperial are all names associated with these various jasper deposits.

The jasper-bearing area is very large, almost four kilometers by six kilometers. Most Imperial jasper has enough color and pattern to be of interest, and very little is mined discarded. The red and pink varieties are the most common. The Royal Imperial jasper is found mostly in the side canyon to the east of the main deposit. The Royal Imperial name is new; when the area was worked 50 years ago, the material was called Imperial jasper. A high percentage of the rock from the side canyon exhibits the pattern found in Bruneau jasper. The name Royal Imperial jasper was recently applied to the rock from this area to distinguish it from the other Imperial jasper varieties. About 18 tons of Royal Imperial jasper and over 80 tons of the other varieties have been produced in the last seven years. This amount is far more than the total historical production of Bruneau, morrisonite, Willow Creek, and Blue Mountain jaspers combined.

Similar Patterns Found in Different Jaspers

There are other jaspers with the pattern of Bruneau jasper that are not well known. Hart Mountain jasper and Rim jasper from Oregon are two of them. There are also thundereggs found in the mountains southeast of Deming, New Mexico, that are filled with this type of jasper. These jasper deposits are small, and pieces are rarely found for sale except in private collections.

At a gem and mineral show in Arizona, I watched one customer look through a tray of Morrison Ranch jasper slabs and exclaim, “Oh, Bruneau!” At another show in another part of the country, a customer looking through the same tray of slabs asked, “Are these Bruneau?” Each of the customers was familiar with Bruneau jasper, yet each suspected that the slabs they were perusing were not Bruneau jasper. They were not familiar with Morrison Ranch jasper. Their responses were trigged by the recognition of the pattern of the jasper from Bruneau Canyon that is so well known. This relatively rare and highly identifiable pattern is associated with all the jaspers mentioned above.

The formation of the orb pattern present in Bruneau, Willow Creek, and Morrison Ranch jasper is independent of the type of geological formation in which the jasper forms. Bruneau and Willow Creek jaspers are both thunderegg formations; that is, the jasper fills the thunderegg’s interior cavity. Morrisonite and Blue Mountain jasper, in contrast, are formed in the brecciated cracking of a welded tuff. Short veins leading to small pockets connected to other veins of jasper are the general rule. Royal Imperial jasper seems to form all by itself in massive, fine-grained ash or altered andesite deposit.

The outside shape of the Royal Imperial nodule is the same shape as the mass of orbs inside.

Pattern Formation Theory

Current theories on the formation of chalcedony (agate and jasper) propose that silica collection goes through a gel or amorphous stage. An increase in silica concentration or some other event triggers the change to a more solid state. The edge or line observed in these jaspers is a visual record of the transformation that takes place when silica changes from its amorphous stage to its more solid form.

The egg pattern is the only pattern that Bruneau jasper exhibits. Jasper that does not have the orb or egg pattern is a plain tan color of little visual interest and is usually discarded at the mine. Thus, Bruneau jasper is strongly associated with the orb pattern, which is why the two customers referenced Bruneau jasper when they recognized the same pattern in morrisonite.

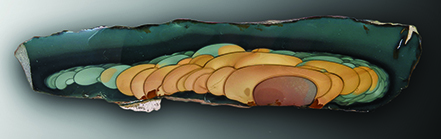

Willow Creek, Imperial Blue Mountain, and morrisonite jasper have different patterns caused by other events that result in a more complex visual experience. This is why many of these types of jasper on the market do not have the egg pattern. They have enough color and other patterns to be visually interesting. According to my observation, only about 25 percent of the morrisonite mined and brought to market has the egg pattern. An exception to this rule is the morrisonite that comes from the Christine Marie claim; like Bruneau jasper, it has little visual interest other than the egg pattern. Some of the Imperial jasper varieties offered for sale have little or no egg pattern, while a very high percentage of the Royal Imperial has the pattern. If a piece of Willow Creek, morrisonite, Blue Mountain, or Imperial jasper exhibits the egg pattern, it is considered a high grade or better piece.

The most common of the other patterns exhibited by these jaspers also goes by several names, including “straws,” “streamers,” and “reseals.” These look like different-colored lines or, when in mass, a weblike pattern. Occasionally, a brecciated pattern can result if the phenomenon that causes the streamers is predominant and occurs in opposite directions. The streamers usually extend from the outside surface of the jasper, where they are thicker across, inward toward the jasper’s center, where they end in a point. Streamers or reseals are formed in the jasper from fractures or separations in the original jasper, which are then filled in with more jasper.

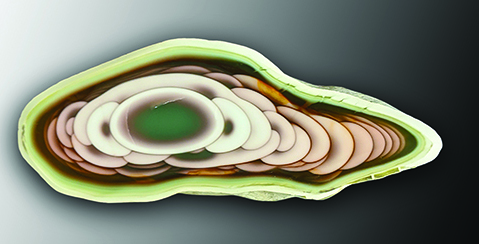

An example of Blue Mountain jasper revealing the color patterns and egg presentation.

The spaces created for the new jasper may result from host rock movement causing fractures or shrinkage separations of the jasper itself as it forms. The jasper that fills these cracks may be similar in character to the original jasper or completely different. Striking color contrasts can occur, as can very subtle ghost-like patterns.

One specimen of Willow Creek jasper has “streamers.” These are lighter in color than the pinkish-tan egg pattern, but some of the egg patterns change color behind the streamer, making the streamer seem translucent. Other streamers in this same specimen are the same dark color of the darkest jasper present. The streamers can form as single, stark lines in the jasper or in such profusion that the visual pattern exhibits a Jackson Pollock art complexity. Streamers, also called reseals, are especially common in the Morrison Ranch and Willow Creek jaspers, though they are not uncommon in Imperial jasper. A variety of Imperial jasper is sold as Spider-web Imperial jasper due to the streamer patterns’ prominence. An interesting and beautiful variation that sometimes occurs in morrisonite jasper is a thick streamer with its own egg pattern!

A polished slab of morrisonite from the Jake’s Place claim in Oregon shows a mass of streamers of different colors flowing over each other from both sides of the jasper seam in such profusion that the center’s egg pattern is almost obliterated. The egg pattern’s ghostly shapes can be seen beneath the forest of streamers. The streamers pick up the color and some of the egg pattern from the jasper beneath. This slab’s visual depth makes it hard to believe this is a flat piece of opaque rock.

One difference in the process of formation of these jaspers, compared to agates, is that the silica is collecting in another substance (previously deposited material) and not in an open cavity. In the case of Bruneau jasper, the substance is homogenous and without form. In the case of Willow Creek jasper and especially Imperial jasper, the substance is layered. This layering can be seen as soft, horizontal banding in the jasper after it is formed. The layering causes subtle color variations in the bands and affects the other formational events’ visual imprint.

If the egg pattern is present, the edge or line can appear visually altered as it moves from one layer to another. Streamers can change color as they cross the layers of the substance. I have seen an interesting and beautiful variation in which the egg pattern formed in only one of these layers; a long, thin series of oval shapes appear in otherwise plain, lightly banded jasper. Willow Creek jasper can have another variation not seen in any of the other jasper in this group. The substance’s layering can actually be folded or curved, causing all the other formational imprints to appear folded or curved.

Much has been written about agate formation without any complete hypothesis to explain the hundreds of variations that occur. The many forms and patterns in agate are explained by one theory or another, and it is apparent that many changes occur in the genesis of an agate. The jaspers, for the most part, have not been examined in the development of these theories. Each agate studied for a particular aspect of its formation shows only the final result of the many formational changes in its genesis.

Because the jaspers that contain the egg pattern are formed in a medium or substance, each formational event or process is visibly represented in the final result. This provides a rich and beautiful visual experience and offers a unique opportunity for study. There is a formational conclusion with agate, but with these jaspers, there is the whole story.

If you enjoyed what you’ve read here we invite you to consider signing up for the FREE Rock & Gem weekly newsletter. Learn more>>>

In addition, we invite you to consider subscribing to Rock & Gem magazine. The cost for a one-year U.S. subscription (12 issues) is $29.95. Learn more >>>

Hide i

Hide i