By Bob Jones

Soldiers’ Discovery Leads to a Century of Mining at Pearl Handle Open Pit

There once was a small town along Mineral Creek in Arizona’s Dripping Springs Mountains called Ray. Today, the town is gone, swallowed up by the huge Pearl Handle Open Pit copper mine, also named Ray. This huge copper deposit was discovered in 1846 and has been steadily mined since 1911.

The Ray mine started as an underground copper mine. Miners working the area followed veins of copper sulfides, chalcocite, and covellite, along with native copper and copper silicate chrysocolla. The mine’s initial discovery is credited to soldiers of the Army of the West (Mexican-American War), and this discovery caused others to prospect for more wealth.

When you look into Arizona’s well-known mines, it is interesting to note how many were found by soldiers based in this vast desert land. The best known of these is Bisbee, where a soldier picked up a specimen of lead carbonate cerussite that lead to the discovery of copper in the Mule Mountains. Not far north of Ray is the Magma mine, in Superior, Arizona, and another rich copper deposit nearby is the now mined out and once rich Silver King mine found in the 1800s by a soldier named Sullivan, who was part of a crew building a new road. The funny thing is that Sullivan couldn’t find the silver mine when he retired and returned to Arizona. The Silver King was eventually found again and produced superb native silver specimens for a few years.

The Early Years

In 1911, Ray was developed as an underground mine with, as I mentioned earlier, miners following veins of copper sulfides. Extensive mining eventually caused some collapses, and by 1952 development of an open-pit took shape. By 1953, the once vast low-grade deposit, now named the Pearl Handle Open Pit, was producing. Early in its operation, the discovery of fine copper mineral specimens in quantity occurred, and even today, as the Pit continues to expand, high-quality collector specimens are encountered occasionally. During those early days in the 1950s of excavating the Pearl Handle Pit, the first significant amount of copper minerals was found in a most unusual deposit just below the surface.

With the desert well known for a zone of caliche soil just below the dirt surface, as water seeps into the ground, it picks up various minerals like calcium carbonate, iron oxide, and others, including copper salts. When the hot sun bakes the ground, the rainwater moves back toward the surface and evaporates, leaving behind the same dissolved minerals as a thick, hard, white cement-like soil layer called caliche. This information was all explained to me by Arthur Flagg, curator of the state mineral museum.

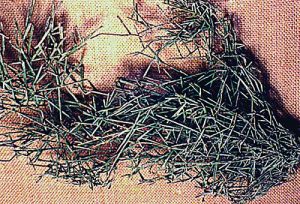

As the Pearl Handle Pit miners broke through the hard layer of caliche present, they exposed a zone rich in clusters of long branching crystallized copper wires coated with bright red crystallized cuprite. Some of the wires were six to eight inches long, and most were hand-sized clusters of branching wires completely coated with crystallized cuprite showing crystal faces. Hundreds of specimens were found and collected by miners. One collector that I knew boasted of having a collection with 150 examples of these copper-cuprite clusters. At the height of the discovery, mineral collectors in the Phoenix and Tucson areas traded citrus and fresh goods from their gardens for these copper wire specimens.

Once the Pearl Handle Pit opened, like any operating mine, the miners took every opportunity to collect specimens revealed by mining. Since the initial find of the copper-cuprite wire specimens, countless tons of copper-bearing rock was blasted and hauled to the crusher. Local landscapers, homeowners, and architects worked the dumps with permission to gather blue chrysocolla stained rocks. The lucky ones also found a copper specimen or two.

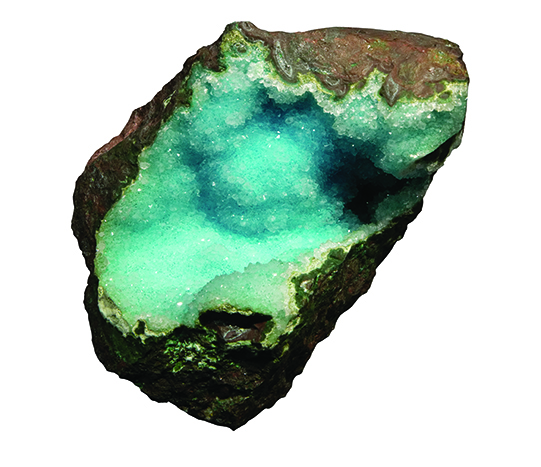

The Ray deposit is one of the largest low-grade copper deposits in the state. During mining, a copper-rich vein would occasionally reveal well-crystallized collector specimens. Among the more exciting finds during the following years included a seam full of superb spinel twinned native copper crystals, as well as a vein with fascinating chrysocolla after selenite crystal clusters, and one remarkable cavity-filled vein full of stalactites of chrysocolla specimens coated with sparkling quartz.

Fine calcites are particularly common here, as are quantities of decorator blue solid chrysocolla, often a choice for architecture. On occasion, a seam with sheets of native copper would also be opened. The mining company often entered into specimen collecting contracts with local dealers, so when crystal specimens turned up, they could be saved for the collector market.

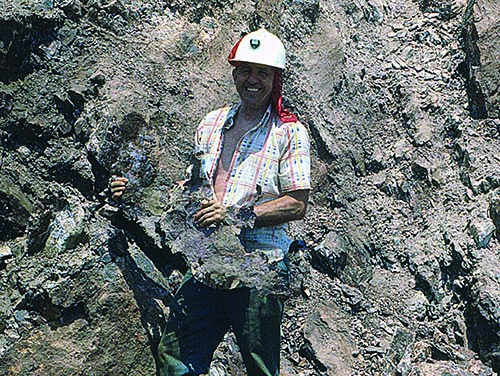

As it happened, one hot August day I was invited to collect at Ray by John Mediz, who had the collecting contract at the time. I made the 60-mile drive early, and we headed into the Pit. Previous mining had exposed a huge zone of native copper filling cracks and seams in the host rock. We quickly went to work, with John collecting the sheet copper and me scouting for any crystallized specimens. We were on the south-facing side of the Pit, and the temperature by noon that day reached more than 100 degrees. I guess collectors will do anything to get specimens!

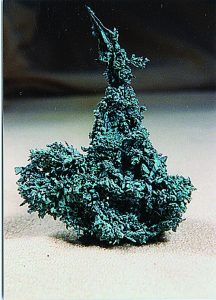

Perhaps the most exciting find at Ray happened several decades ago before specimen contracts were offered. After a massive deposit of crystallized spinel twinned native copper was opened, miners, shovel operators, and truck drivers were able to salvage most of the available specimens.

Spinel twinned copper crystals form as flat-bladed crystals, with each crystal usually a half-inch or so in size at the base where it is attached to another crystal sharing a common plane. These crystals attach to other crystals end-to-end to form a long V-shaped elongate crystal group with perfectly straight sharp edges. All of the copper crystals were spinel twinned in clusters, sometimes reaching ten inches in length. These twins were loosely attached, and miners simply pulled specimens apart, making small to very large examples that easily filled both hands. Some crystals were still attached to big chunks of rock, which the miners gathered and carried off.

Another exceptional feature of these twins was their color. Instead of being a dark coppery color from long exposure to weathering, these beauties were covered by a lovely lustrous and sometimes velvety malachite green patina. These twin specimens rank as some of the most beautiful copper specimens ever found in Arizona.

Modern Discoveries

Fast forward and, about seven years ago, my son Evan was invited to collect in the Ray Pit. They were finding small one- and two-inch-long spinel twinned coppers. So we headed to the Ray Pit, met Evan’s friend, and collected spinel twinned coppers though none had the malachite coating. Collecting was easy because we just followed a road grader that was turning over the dump area.

Some of the prettiest specimens to come from Ray are the light blue clusters of crystals initially offered for sale as chrysocolla after azurite. Specimens of crystals were attached at random angles; some were well terminated, and all striated in a flat lathe-like form, with some broken while being collected. Most groups were a bit brittle, so none of the groups were large. Most were about hand-sized. While handling these specimens, I realized they were chrysocolla but not after azurite crystals. Azurite very seldom has striated prism faces, and though both azurite and selenite crystals are monoclinic, these beautiful pale blue crystal groups were very likely chrysocolla pseudomorph after selenite gypsum. Regardless, they are beautiful and worth having if you can find one.

All told, I think the most significant find at Ray came when mining tore out a colossal seam full of cavities lined and filled with stalactites of chrysocolla hanging like so many ice cycles in the openings. The variety of forms, the intense light blue color, the size of some stalactites, and the brilliant drusy quartz coating on most of the examples made them some of the most handsome chrysocolla stalactites ever found, in my opinion.

Some of the stalactites were six to eight inches long. Others had grown long enough to be columnar instead of free-standing. Most were in tight sub-parallel clusters jutting from a common base of solid blue chrysocolla and standing in clusters just fractions of an inch apart. Some were curved as if influenced by the directional flow of water carrying the copper mineral in solution.

If these blue beauties were pure chrysocolla, they would have been well worth collecting, but most were also coated with bright, sparkling drusy quartz crystal points, making them eye-catching. The quartz druse, in some cases, is transparent, so the intense blue color comes through. This find was huge, so big the company employed a friend of mine, Andy Clark, local miner and expert collector, to mine the specimens and prepare them for sale. Individual pricing was out of the question because of the great number of specimens, so Andy grouped them in lots of six or more specimens per lot, with each lot including a nice variety of specimens. Collectors and dealers were invited to view and bid on the specimens. My son Evan bid on and won some lots, which he had no trouble selling.

The Ray mine is still active, and we can always hope for another big find of spinel twinned coppers or something just as exciting.

Author: Bob Jones

Holds the Carnegie Mineralogical Award, is a member of the Rockhound Hall of Fame, and has been writing for Rock & Gem since its inception. He lectures about minerals, and has written several books and video scripts.

Holds the Carnegie Mineralogical Award, is a member of the Rockhound Hall of Fame, and has been writing for Rock & Gem since its inception. He lectures about minerals, and has written several books and video scripts.

If you enjoyed what you’ve read here we invite you to consider signing up for the FREE Rock & Gem weekly newsletter. Learn more>>>

In addition, we invite you to consider subscribing to Rock & Gem magazine. The cost for a one-year U.S. subscription (12 issues) is $29.95. Learn more >>>

Hide i

Hide i