Careers in geology were not always an option for women. A few brave women paved the way for today’s young women to choose any career—scientific, artistic and more.

Here’s a closer look at four, very different, talented women with careers in geology—one is an archaeologist, geologist, explorer and business owner; another, an award-winning, self-taught, wire-wrapping artist; another, was an educator, professional geologist and philanthropist and the fourth, a student, the professor’s legacy.

Careers in Geology: The Archaeologist

In September 1987, National Geographic Magazine published an article about jade that told the story of a man and his wife who discovered the source of Mayan jade in the jungles of Guatemala. In March 2023 this author spent several hours with the amazing woman featured in that article while visiting Jade Maya Factory in Antigua, Guatemala.

The story of Mary Lou Ridinger and her late husband, Jay lies on the Mayan-Mesoamerican path where archaeology and careers in geology merge. They are credited with finding several sources of Guatemalan jade of various colors as well as re-establishing the Guatemalan jade carving industry.

Born in Texas, Mary Lou is an American ex-pat, with a bachelor’s degree in Latin American studies from the University of Colorado, Boulder, and a master’s in archaeology from the University of the Americans in Mexico City. She continues to run the Jade Maya Factory in Antigua, Guatemala, founded with her late husband in 1974.

Jade Maya Factory

Located in the quaint town of Antiqua, surrounded by active volcanoes about an hour and a half drive from the cruise port of Puerto Quetzal, Guatemala, the factory is known for its jade replicas of ancient Mayan treasures as well as fine jewelry items. On days when a ship is in port, as many as 800 tourists visit Jade Maya and on most of those days, visitors get a personal lesson about jade directly from Mary Lou before touring the workshop and gallery.

Adobe Stock / By Artem

The Jade Classroom

We sat in the room of 50 or so chairs, surrounded by jade replica artifacts and photos from Mary Lou’s expeditions. Every 20 minutes or so, she would excuse herself from our discussion to greet a new group of tourists, giving them her eight-minute presentation. Mary Lou’s enthusiastic talk made sure that everyone in the room left knowing what jade is and is not, where it was found, the different kinds of jade and how it was used by the Mayan people. She demonstrated her rockhounding field technique of hitting a piece of jade, with a hammer that needs to be replaced about every two years, so everyone could hear it ring.

After the presentation, visitors explore the workshop where they can observe several local workers as they carve and polish both the artifact replicas and jewelry for sale in the factory’s gallery.

Tourists can wander at their leisure through the various rooms and courtyard that make up this large complex. There are mineral samples as well as displays of recreated archaeological artifacts. There is even a jade marimba on which, from time to time, a tourist may strike up a few notes.

Visitors to Jade Maya all seem to meet Mary Lou’s goal of ensuring that “everyone who visits leaves learning something new about jade.” As for exploring, these days, Mary Lou’s son carries on her legacy of exploring the Guatemala countryside for new sources of jade.

Jade Maya Challenges

Jade Maya Factory has faced setbacks in tourist trade since its inception in 1974. Cycles of civil unrest and the pandemic shutdown were hard on the business. It is the volcanoes surrounding the town of Antigua that bring tourists to the area and Jade Maya but also hamper their ability to get there.

Fuego, a stratovolcano located about 12 miles southwest of Antigua, is one of the most active and dangerous in the region. It spews an explosion of gas and ash into the air every 15 to 20 minutes, visible from the road on the way to Antigua.

A major eruption on June 3, 2018, resulted in 159 deaths and at least 300 injuries. This eruption destroyed the main road from Puerto Quetzal to Antigua which has since been rebuilt.

The Jewelry Maker

On the first night of an 18-night transatlantic cruise from New York City to Lisbon, Portugal, a chance meeting and conversation with a woman wearing a beautiful Larimar pendant wire wrapped in a nautical theme, provided a great start to a cruise and a new friendship.

Julie Park and her husband, Howard, have traveled the world collecting raw minerals, cabochons and carved gems which Julie hand-crafts into one-of-a-kind treasures, wire wrapped in gold, silver or copper. The couple used this cruise, with its numerous sea days, not only to rest from a busy craft show schedule but to create new treasures to sell at upcoming shows.

On sea days, Julie would create her pendants as we discussed her background and training. She often worked with copper and when asked if she ever wrapped any Native copper—a popular mineral from the UP of Michigan, the answer was “No.” With a promise to mail some copper nuggets to her home near Salt Lake City, Utah, our return home, we continued our conversation.

Art, at the Heart of All Her Careers

Julie is a self-taught wire wrapping artist who won “Best in Show” at two Utah State Fairs. She developed her love of rocks and minerals working as a manager for an Australian Opal and Mineral business; took a silversmith class, developed a large clientele and spent several years as a professional photographer, specializing in weddings.

She took a wire wrapping course but quit after just a few sessions. She continued to read articles about wire wrapping and producing pendants until she developed her current style.

Today, Julie’s business, Treasures For Me, operates online and at several rock and mineral shows, gun shows, boutiques and metaphysical shows every year. Julie tries to know her audience and prepares pendants and displays especially for each show. She prides herself in the knowledge that “every stone has a story.” And, given the chance, Julie will tell you the story of each pendant she sells.

*Note: Julie made a beautiful wire-wrapped copper nugget for the author from one of the samples sent to her after the cruise.

The Professor

In 1970, in an auditorium-sized classroom at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (UWM), a professor lectured on physical geography. She often showed slides of her, and her husband’s summer treks to geological features throughout the western United States.

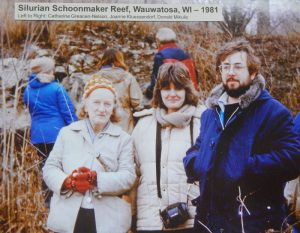

A search by the UWM archives department could not prove nor disprove that Dr. Katerine Graecen Nelson was the author’s professor for this elective class so many years ago, but conversations with people who knew her, indicate she was just that.

Katherine attained a bachelor’s degree from Vassar in 1934 and a Ph.D. in Geology from Rutgers University in 1938. During WWII she worked for the Shell and Hunt Oil companies in Texas before moving to Milwaukee and joining the faculty of Downer College.

In 1956, she joined the faculty of UWM where she soon became the first chairperson of the Department of Geological and Geophysical Sciences and continued teaching there until she died in 1982.

Lifetime Achievements

Dr. Nelson was responsible for securing the Thomas A. Greene Museum of Minerals and Fossils for the UWM Department of Geosciences from the former Downer College. The museum is housed on the UWM campus and is currently open to the public Monday through Thursday, but days and hours vary so check their website before visiting.

Devoted to teaching others about the earth, Dr. Nelson was equally comfortable escorting a group of grade-schoolers visiting the Greene Museum as she was writing one of her many published scientific papers.

Other Accomplishments

• Fellow of the Geological Society of America, American Association of Petroleum Geologists

• Midwest Federation of Mineralogical and Geological Sciences “Educator of the Year—1982”

• Honorary curator of the Milwaukee Public Museum

• First woman president of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters. She remained on the governing board until her death.

• Honorary member of the Wisconsin Geological Society (WGS) where she served as president in 1934-35

Also, two scholarship programs benefiting current and future UWM Department of Geosciences graduate students were established in Dr. Nelson’s name—The Nelson, Cherkaur, Lascar Legacy Scholarship and the Wisconsin Geological Society’s Endowment Fund.

Photo courtesy Allison Reann Kusick

Students Getting Started with Careers in Geology

Just starting her career in geology, Allison Raeann Kusick, a second-year Ph.D. student in Glacial Sedimentology at UWM, recently spent several weeks in the San Juan Province in western Argentina doing fieldwork to interpret a section of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age with her professor, John Isbell and first-year master’s student, Cole Schmidt.

Allison received the WGS Endowment Scholarship in 2022 and the Nelson, Cherkaur, Lascar Legacy Scholarship from UWM in May 2023. Proceeds from both scholarships plus combined scholarships and grants of her co-participants helped to fund the expenses of the fall, 2023 field trip to Argentina.

Allison is active in all segments of the UWM Geosciences Department. Recently she accompanied the group, helped man their booth and gave a presentation at the annual meeting of the Geological Society of America in Pittsburgh.

Well on her way to making her mark on the geological world, Allison has recently accepted a pathways position with the United States Geological Survey (USGS), as a federal research geologist, mapping Quaternary deposits of the Great Lakes Region.

Careers in Geology: Past, Present & Future

Knowing that women have not always been afforded the same opportunities for careers in geology and recognition as their male counterparts, let’s celebrate the accomplishments of these four ladies with their careers in geology and all the women in our lives who paved the way for women past, present and well into the future. Well done, ladies!

This article about women and careers in geology previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Story by Sue Eyre. Click here to subscribe.