Caves of the national parks are some of the world’s biggest and most interesting caves. Within its 189 national parks and monuments, the National Park Service (NPS) has documented more than 4,700 caves. Some are smaller than a basketball court, while others have hundreds of miles of twisting passageways.

Dark and mysterious, bewitching and beautiful, caves instill fear, spark the imagination, and delight the senses with their winding passageways, surreal stone features and subterranean grottos. The mystique of caves attracts everyone from explorers and scientists to tourists and the casually curious.

Defined as natural voids in the ground large enough for human entry and with depths that exceed the width and height of their openings, caves are classified by origin as solution, lava, talus, sea or lake, or ice.

Caves of the National Parks – Solution Caves

Solution caves, the most abundant type of cave, form by the dissolution of rocks such as limestone and marble. The solvent is usually carbonic acid, a weak acid that forms when atmospheric carbon dioxide dissolves in surface water, and then percolates downward through bedrock fissures.

Most solution caves form in limestone, a sedimentary rock consisting largely of calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO3). Because limestone dissolution and cave formation progress at an average rate of just one millimeter per year, the development of a cave can take hundreds or thousands of years or more.

Mammoth Cave

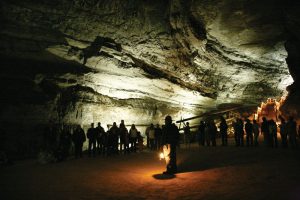

A solution cave in south-central Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave National Park, is the world’s largest cave, with 430 miles of surveyed passages. Natural development continues today on the cave’s lowest level 350 feet below the surface.

Over thousands of years, this cave’s thriving bat population has deposited large quantities of guano rich in nitrates that are easily converted to saltpeter (potassium nitrate), the key component of black gunpowder. During the War of 1812, Mammoth Cave provided much of the nation’s saltpeter, which was mined by enslaved African Americans. When Mammoth Cave began attracting tourists after the war, these same African Americans became the nation’s first underground tour guides.

Among Mammoth Cave’s many unusual calcite deposits or speleothems are “cave flowers”—rosettes of long, hair-like gypsum crystals that grow on flat and curved surfaces, freestanding shapes called “ram’s horns.”

Carlsbad Caverns, Lechuguilla, Slaughter & Spider

Southeastern New Mexico’s Carlsbad Caverns National Park is the home of Carlsbad Caverns and Lechuguilla, Slaughter and Spider caves. Carlsbad Caverns is a sprawling system of 119 interconnected caves, among which are some of the largest, longest and deepest in the world. Carlsbad Caverns is unusual because it was created not by carbonic acid, but by sulfuric acid derived from hydrogen sulfide gas that rose from deep petroleum deposits to dissolve in groundwater. Attractions include the 4,000-footlong, 250-foot-high Big Room, North America’s largest underground gallery.

Hanging from the roof of Lechuguilla Cave are the largest-known gypsum stalactites—20-foot-long, white stalactitic chandeliers that are named for the delicate sprays of colorless selenite crystals radiating from their tips. Until the 1980s, Lechuguilla was assumed to be small, but explorers have since found 145 miles of previously unmapped passages, some as deep as 1,600 feet.

Wind Cave

Wind Cave in southwestern South Dakota’s Wind Cave National Park is named for the wind that blows through its entrance with changes in atmospheric pressure. Although this relatively dry cave has few stalactites and stalagmites, it is known for a wide variety of striking calcite speleothems with evocative names like gleaming “dogtooth” crystals, needle-sharp growths of “frostwork,” nubby bumps of “cave popcorn” and, most notably, rare, honeycomb patterns of crystals called “boxwork.”

Jewel Cave

Nearby Jewel Cave in Jewel Cave National Monument is named for the glittering calcite crystals that cover its walls. Although initially thought to be small like New Mexico’s Lechiguilla Cave, recent explorations have revealed 192 miles of passageways, making Jewel Cave the world’s third-largest cave.

Timpanogos Cave

Timpanogos Cave in Timpanogos Cave National Monument in Utah’s Wasatch Mountains features numerous examples of fragile speleothems called helictites —sideways stalactites that form when capillary action causes calcite to precipitate as thin, horizontal or downward angled tubes. Timpanogos’ other unusual speleothems are the imaginatively named “cave bacon” and “cave popcorn” structures, along with frostwork and beautiful formations of flowstone.

Lava Caves

Unlike solution caves, lava caves, or “lava tubes,” form simultaneously with their host volcanic rock when volcanoes erupt and flows of surface lava melt downward into channels. Overflowing and splashing lava solidifies into walls that sometimes build into overhead crusts. When eruptions cease, molten lava drains from enclosed channels, leaving behind caves often adorned with lava stalactites called “lavacicles.”

Wikimedia Commons

Northern California’s Lava Beds National Monument has North America’s greatest concentration of lava caves. Of the park’s 700 lava caves, 25 are open for self-guided or ranger-guided exploration. Winter tours of Crystal Ice Cave showcase exquisite white-ice formations gleaming against black-lava walls; summer tours highlight Fern Cave’s Native American rock art and lush underground vegetation.

Idaho’s Craters of the Moon National Park and Preserve encompasses the largest lava field in the lower 48 states. This 50-mile-long lava field consists of 60 individual flows from eight major eruptions. Five of the lava caves are open to the public, among them the 800-foot-long Indian Tunnel, which is accessible from both ends.

The Thurston Lava Tube is a popular attraction at Hawaii Volcanoes National Park on Hawaii’s Big Island. Formed just 500 years ago, this 600-foot-long, 20-foothigh lava cave features drips and waves that are the solidified remnants of lava that emanated from the Kilauea volcano.

Talus Caves

Talus caves are openings between heaps of large boulders. They form at the base of steep slopes when erosion triggers the downhill movement of large angular boulders. Talus caves, most common in the Appalachians and the mountainous West, are characterized by tight, twisting passageways and multiple entrances.

In California’s Yosemite National Park, Pleistocene glacial scouring and subsequent rockfall from sheer cliffs have built huge talus piles with caves as long as 300 feet.

California’s Pinnacles National Park protects a rugged, 23-million-year-old volcanic field of rhyolitic rock. During the Pleistocene ice ages, massive ice sheets scoured huge boulders into narrow gorges to create massive talus heaps laced with dozens of caves.

Sea & Lake Caves

Sea and lake caves are created along rocky shores and the headlands of oceans and large lakes by waves coupled with the abrasive action of waterborne sand. The shorelines of California’s Channel Islands National Park and Point Reyes National Seashore, and Maine’s Acadia National Park, are laced with dozens of sea caves.

At Michigan’s Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore and Wisconsin’s Apostle Islands National Lakeshore, wave action and repetitive cycles of freezing and thawing have sculpted sandstone shorelines into spectacular networks of lake caves featuring delicate arches, vaulted chambers and honeycombed passageways.

Ice Caves

Caves with ice as a major feature fall into two categories: Ice caves are caves that contain some ice year-round, while glacier-ice caves exist within masses of glacial ice. Ice caves trap frigid winter air and remain cold enough to retain ice formations even in summer. Lava caves that double as ice caves are found in Idaho’s Craters of the Moon National Park and Preserve, New Mexico’s El Malpais National Monument, California’s Lava Beds National Monument and Arizona’s Sunset Crater National Monument.

Glacier-ice caves originate when creeks flow into glaciers through moraines to melt voids with ice roofs and walls, and bedrock or sediment floors. Eerie, bluish light filtering through translucent, overhead ice imparts a surreal beauty to glacier-ice caves.

Wikimedia Commons

Alaska’s national parks are famed for their many glacier-ice caves. Creeks continuously melt out new glacier-ice caves within Root Glacier in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, the world’s largest glacier system. Other Alaskan national parks with glacier-ice caves are Katmai National Park and Preserve, Kenai Fjords National Park and Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve.

Caves of the National Parks – Management Today

When the National Park Service was established more than a century ago, its resource managers did not understand the environmental fragility of caves, especially of solution caves. For the convenience of visitors, they built infrastructure directly atop the caves, installed elevators to quickly whisk visitors in and out of caves, and constructed underground trails that, while showing off underground scenery, were detrimental to the cave environment.

Appreciation of the environmental uniqueness of caves emerged in the 1970s. In 1988, the Cave Resources Protection Act mandated that potential environmental impacts on caves be considered before undertaking surface-development projects. A decade later, the National Cave and Karst Research Institute Act established a federal research center for cave conservation.

New Cave Discoveries

In just the last two decades, dozens of previously unknown caves with more than 100 miles of passages have been discovered, explored and documented within the national parks. A voluminous, newly compiled information database now aids the formulation of cave-management policies and the upgrading of educational exhibits and signage for the benefit of park visitors. With science continuing to unravel more of their mysteries, there has never been a better time to visit the many caves of America’s national parks.

Fun Fact: Precipitation, the opposite of dissolution, occurs when decreased acidity and temperature cause dissolved minerals to crystallize into such unusual features as drapery-like flowstone, icicle-like stalactites, spire-like stalagmites, “cave flowers,” twisted helictites and columns connecting floors with ceilings. These features are collectively known as speleothems, from the Greeks words splaion, meaning “cave,” and thema, “something laid down.”

This story about caves of the national parks previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe! Story by Steve Voynick.