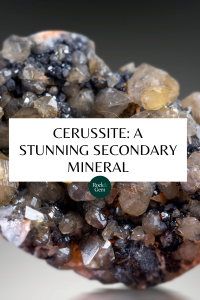

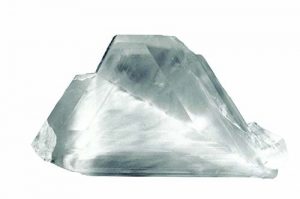

Cerussite is a transparent to translucent secondary mineral. When colorless, high lead content gives it brilliant luster and makes it the heaviest of all transparent crystals. This lead carbonate was known as “white lead” in the old days.

Galena: A Primary Mineral

Galena is not exactly a showcase mineral. You seldom see it prominently exhibited at shows. It does form in very attractive cubes and octahedrons and even twins, but its strong gray-black color or unusual crystal forms do not exhibit well. But what galena lacks in eye appeal, it makes up for as the source of delightful and colorful daughter minerals.

Using decomposing galena, Mother Nature produces a wonderful suite of secondary lead minerals. Reaching deep into the earth — at times over 1,000 feet in desert regions — surface waters charged with oxygen and plant acids attack deep-seated sulfide ores, including galena, breaking down to release lead ions and combine with carbonates, sulfates, arsenates, or oxides. The process produces common colorful beauties like wulfenite, mimetite, pyromorphite vanadinite, and cerussite in abundance. Rare lead minerals like leadhillite also form.

Cerussite’s Striking Crystal Formation

Cerussite colors can appear as pale tan, pale green, bluish, yellow or some other tint due to another mineral included as an impurity. Color plays only a minor role in the mineral’s value. Far more interesting and appealing is cerussite’s almost ingrained habit of forming any one of several twin forms, all very attractive and even beautiful. Unlike most crystals that twin, made up of two crystals, cerussite goes a step beyond ordinary twinning by combining several dozen crystals to twin in a very attractive unusual physical feature. Cerussite forms a greater assortment of twin forms than any other mineral, so these twins are most appealing and valuable whether the twin is stark white, has a tint of color, or is water clear.

In addition to the varied and noteworthy twinning habits of cerussite, it’s interesting to learn the mineral crystallizes in the orthorhombic system. The term “ortho” indicates that the crystal has three internal axes around which it forms. Each axis is at an aright angle, just as in a cube, like a fluorite specimen. Orthorhombic crystals have rhombic faces, which means that every orthorhombic species crystal face is slanted, not square, and angled. Still, all slanted sides are at a right angle to each other. You see this best when a cerussite crystal is tabular. But cerussite does not form simple tabular rhombs very often. Instead, it tends to develop long, slender crystals with slanted faces or as twinned crystals attached at the base, at an angle of about 60 degrees.

The simplest of these cerussite twins form as a “V,” sometimes called an elbow twin. These are the most common twinning forms of cerussite. But even a simple V twin can take on a very pleasing variation as each crystal face is slightly rounded. The reentrant angle, wide open in a V twin, can fill in, becoming a small notch that gives the twin a three-dimensional heart shape, thick and rounded.

Things get a bit complicated when three pairs of twinned cerussite crystals attach side by side to form a six-crystal hexagon shape. The overall hexagon form, referred to as a sixling twin, resembles an aragonite sixling hexagonal twin. Such sixling cerussite twins are referred to as pseudo-hexagonal because they mimic a hexagonal species’ six-sided shape. Pseudo-hexagonal cerussites are flat-sided and have a flat termination on which you can often see a chevron pattern revealing the twin habit. These are not the only cerussite twinning forms.

Twinning Habit Appeal

The twinning habit I like the best is when the cerussite crystals reticulate. This term means crystal after crystal forms as an interconnected network of many cerussite crystals, and each crystal grows into the next at a nearly 60-degree angle. The crystals are usually not large, about an inch or so long, as each crystal is interrupted by other twinning crystals. The twin’s overall size, however, can be several inches across the crystal network. There seems no limit to how many cerussite crystals can join to form a reticulating twinning network. Oddly, the cerussite twins only grow in a two-direction form. The overall network of reticulated twinned crystals is flat, often under an inch thick but many inches across. This “flat” crystal network is an open arrangement, which means there are spaces between the crystals that are triangular; plus, every crystal is in an orderly position to all the crystals around it as if carefully positioned. Talk about geometric beauty!

But Mother Nature is still not finished twinning her cerussite. We used the term snowflake earlier, and that is precisely what cerussite can form, twins that look like a snowflake. The crystals are usually snow-white in a perfectly orderly flay sixling pattern, but with reticulating crystals between the six main crystals. The result is a twin cluster like an intricate snowflake. Some of the finest examples of twinned snowflake cerussite are found in Tsumeb, Namibia, and often command the highest price.

Notable Cerussite Deposits

Tsumeb is the amazing multi-oxide deposit that has produced several hundred different mineral species, including an astounding number of cerussite specimens. A significant volume of Tsumeb cerussite has been mined, but there are still examples available for purchase. I can recall the annual Tucson Show a couple of decades ago when it seemed every mineral dealer was offering several flats of nice twinned cerussite specimens for sale.

Tsumeb may have been the most active producer of cerussite in the last couple of decades, but interestingly the Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, area was a significant producer during the Civil War. A cluster of mines around this area, generally referred to as the Wheatley mine, was managed by Charles Wheatley. During this time in history, the site produced an excellent selection of cerussite, and on occasion, a Wheatley specimen is still seen for sale today. These mines had fine pyromorphite, anglesite, and other notable lead and copper minerals in addition to cerussite. It is always a good idea to add such historically treasured minerals to any collection.

Morocco’s lead mines have also been a fine source of cerussite twins, with some of them approaching three inches across. The better twins from here are transparent in sharp-edged V twins two and three inches in length. Other crystals of lesser size are often slightly cloudy, with each crystal slightly rounded and lustrous. There have been times when healthy quantities of superb cerussite twins have come from here in the last decades. It is likely cerussite from Morocco will be found again.

One of the better U.S. sources for cerussite in the U.S. has been the silver mines around Kellogg, Idaho, now closed. In the months before the mines closed, a large fine crystallized twinned cerussite was opened and collected. Specimen collectors collected groups of white twins bordering on transparent with some of the clusters several inches across. Other cerussites from here are typically white in small twinned groups. However, it is often overshadowed by the wonderful pyromorphite from the location.

About 60 years ago, I was visited by a miner from Kellogg who had several flats of small white cerussite crystal clusters for sale. Most specimens were only a couple of inches across, not exceptionally lustrous, and some showed a little damage around the edges. Given the fragile nature of cerussite, it’s not surprising. The only thing that made these cerussites interesting were tiny silver wires sticking out from between the cerussite crystals. Each cerussite group had one or two such silver wires visible. Idaho cerussite, especially with silver, were seldom seen in Arizona at the time, so I was interested in buying some. But on careful examination with a glass, I could see a couple of the cerussite specimens had the silver wires added, lightly glued in place between the cerussite crystals, and I certainly didn’t make the purchase. I mention this only to remind readers when buying specimens of any mineral to check it carefully. With today’s modern glues and enhancing methods, you have to be careful.

An excellent place to view some fantastic cerussite specimens is the Mineral Museum at New Mexico Tech. Years ago, the Stevenson-Bennett mine, Organ Mountains, yielded choice V twinned cerussites of fantastic size. The largest twin I saw from this locale measures about seven inches long, slender, tapered, and with a slightly smoky appearance. At one time, I had a very similar V twin cerussite from Tsumeb that almost rivaled the New Mexico twins.

My favorite collecting site for cerussite is in the Patagonia Mountains along the Arizona-Mexico border at the Flux mine. This mine produces an entirely different type of cerussite called Jackstraw crystals. Jackstraw cerussite is snow white but occurs in unusually long spiky brittle crystals, seldom a fraction of an inch wide but approaching many inches in length. The crystals show no noticeable faces but are found in tight sub-parallel bundles and as free-standing nail-like spikes on matrix. Collecting at the Flux mine, Patagonia Mountains, Arizona, was a lark, as the cerussite was found in massive clusters more or less filling open veins in the surface pit. This area was also home to a beautiful Great Horned owl who always resented our noisy visits.

I’ll leave you with one of my favorite cerussite collecting stories. Friends of mine were collecting at the Flux, and they collected so much jackstraw cerussite they ran out of packing material. One friend went to the general store in town and bought up all the toilet paper. The local sheriff was also in the store and became suspicious, as toilet paper is used in some drug production. The collectors were taken into custody and had a heck of a time explaining themselves until they showed the collected cerussite. Eventually, my friends were released, but their cerussite was not!

You never know what you’ll encounter when you go collecting, but what you can be sure of is that cerussite is a fine mineral to collect in a variety of forms.

This story about cerussite previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe! Story by Bob Jones.