By Rebecca Solon

In the March 2020 issue of Rock & Gem, in my article entitled Cherishing Chert: A Mother Rock for the Ages, I discussed the ancient origins of chert as a building block of Earth’s early ocean basins. I illustrated my narrative with two famous formations, the Kaibab Cliffs of the Colorado Plateau and the banded iron formations (BIFs) of Mingus Mountain in the Black Hills region of north-central Arizona.

These ancient deposits crop out at the top of Mingus Mountain and are the source of the hematite and jasp-chert BIFs of the Verde Valley. Chert is a name that is often used interchangeably with another impure opaque variant of chalcedony known as jasper thus the use of the term “Jasp-Chert.” The unique rocks described in this article combine distinguishing characteristics of both varieties and constitute minerals of the chert complex.

Chert-Based Minerals Combine All Rock Classification Categories

The chert-based Kaibab and BIF rocks containing calcium and magnesium-carbonate and iron oxides constitute just a few chert minerals commonly found in Arizona and are now known worldwide. These mineralized rocks establish the complex of chert formations that encompass Earth’s fundamental stratigraphic units as defined by the Geologic Time Scale, and the study of physical geology.

By using the term “complex” this author intends to define units of chert formations further as composed of rocks of two and often three of the standard classifications of sedimentary, metamorphic, and igneous rocks. The chert complex contains a myriad of mineral inclusions that are found globally within these stratigraphic features, both as trace elements and as complex combinations of minerals.

Chert is normally considered to be a sedimentary rock.

But there are now multiple variations being scientifically studied and shown worldwide that contain multiple minerals and patterns. Most chert rocks contain some quartz which accounts for its dense microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline composition. Concerning its typically high quartz content, chert can be an organic or inorganic precipitate or a replacement product in sedimentary rocks.

According to the reference page https://mrdata.usgs.gov/geology/state/sgmc-lith.php?text=chert Chert is defined as “A hard, extremely dense or compact, dull to semivitreous, microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline sedimentary rock, consisting dominantly of interlocking crystals of quartz less than 30 micrometers in diameter.”

Chert is normally classified as a biogenic or organic form, but there are numerous examples of inorganic chert rocks from Arizona.

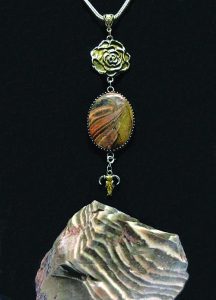

My mentor Cliff Montgomery sold me several beautiful, tumble-polished pieces of Arizona pastelite chert, which I made into interchangeable necklaces. A related species collected by Stan Celestian is a highly patterned pastelite variety from Burro Creek, Arizona, that he has named “Picasso Chert.” His photo collection features this specimen and includes one with differential weathering in a rough and unpolished chert specimen from this locality. The unique weathered surface is described as having a rillensteine pattern. The Dictionary of Geological Terms defines “rillensteine” as “Tiny solution grooves, of about one millimeter or less in width, formed on the surface of a soluble rock [from German, meaning ‘rilled rock’]”.

In 2009 an Arizona Geological Survey Team discovered an opaline variety of chert layered within a travertine formation in the McDowell Sonoran Preserve as a desert precipitate in Scottsdale, Arizona. According to the authors, “Limestone has not been identified previously in the McDowell Mountains or in the metro Phoenix area … The limestone deposit overlies or rests on a larger area of metamorphic rhyolite rock. The meta-rhyolite, a rock rich in silica, likely is the source of the mineral constituting the chert.”

Investigators prepared a thin section of a sample for photo-micrographic examination. The study team identified these geologic events; 1) original travertine limestone deposition; 2) formation of orbicular (concentrically-layered spheroidal) chert and possibly dissolution of limestone; followed by 3) coatings of calcite, silica, and possibly algae in cavities; and finally, 4) void-filling by coarse calcite in a water-saturated environment.

The McDowell Sonoran investigation of a deposit of opalized chert illustrates a prime precipitation event by silica and the mineral SiO2. Opal is hydrous silica (SiO2·nH2O). Technically, opal is not a mineral because it lacks a crystalline structure, so it is typically referred to as a mineraloid. This opaline variety of chert was created in a natural opaline formation as a part of a unique limestone-depositional event.

Progenitor of Durable Mountain Vistas

Chalcedony and quartz minerals play important roles as strengthening components that produce the nearly indestructible varieties of chert that have outlasted many geological eras. One good example is the Mogollon Rim, a geological feature that skirts the northern half of Arizona and forms the southern edge of the Colorado Plateau in Yavapai County, ending near the border with New Mexico. The Mogollon Rim is a complex assemblage of mineral constituents and is representative of the chert complex of Arizona.

These massive Paleozoic limestone-chert formations are remnants of coral reef outcrops of the Mogollon Rim seabed deposits.

Now at over 6,000 feet elevation in the Payson-Pine rimstone region, the Mogollon highlands were originally part of a vast inland sea 225-280 million years ago — the Triassic-Permian periods. Since that time, the original seafloor now sits at a much higher elevation through uplifting from plate tectonics, reaching 8,000 feet at its maximum height.

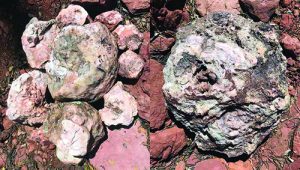

In addition to fossil fragments, these chalcedony-rich rocks incorporate a great many chert and jasper minerals. During a November 2018 field trip to the Payson area of Arizona, we collected pink jasper nodules and the boldly banded chert known by local area rockhounds as “Zebra Stone.” These sedimentary and igneous mixtures of weather-resistant minerals form a rugged topography of gravel sediments that were transported by ancient river systems and deposited in central and northern Arizona.

An older Paleozoic layer of the Rimstone strata that contains nodules of cherty coral and

mollusk fossils is known as the Martin Formation. These rocks are dated at approximately 375 million years and were deposited during the Devonian Period. The variable sedimentary rocks of this formation constitute a cliff-forming limestone member of the Mogollon Rim that has created deep, sheer-walled canyons containing vertebrate fossils along with sea sponge reef casts of stromatoporoids and other invertebrate reef-forming species.

Chert occurs just as commonly as layered or bedded deposits such as in the BIF specimens that exhibit ocean iron-precipitate bands from the oxidation of iron in ancient oceans. According to the web site http://www.galleries.com/rocks/bif.htm

“Banded iron formations are found in the continental shield of all continents of the world. The shield areas of continents contain the oldest Precambrian rocks. At one time these rocks may have been together as one continent, but later broke apart and became the core of the modern continents as they exist today. Although each continent has had its own geologic history that had its own impact on their shield rocks, it is somewhat amazing that most BIF rocks are very similar in character. This is truly one of the most amazing rocks found on Earth.”

I have discovered that variations of chert such as the jasp-chert rocks known as BIFs contain constituents of metamorphic and igneous mineral groups. The BIF deposits in the Verde Valley are compact, massive rocks. My experience collecting a range of sample specimens of these ancient fractured specimens, especially those attributed to local, scenic formations, led to an epiphany.

As a known biogenic source of limestone, chert literally holds up the red rock formations of Sedona and the Grand Canyon. These strong limestone cliffs overlie soft slopes of undercutting sandstone. The vast protective plateaus actually slow the progress of erosion. This Paleozoic chert has endured since the Permian Period due to its plethora of marine organisms whose calcareous remains have been replaced by silicon dioxide, or quartz, the main rock-forming mineral of all the categories of rocks – igneous, metamorphic and sedimentary. It is also one of the major rock-forming minerals of chert, the subject of this article, and a mother rock for the ages of life’s tumultuous history.

Chalcedony, a cryptocrystalline variety of quartz, has a vitreous luster and is the material that makes up much of the chert found in the Verde Valley. During my field trips throughout the area, I have collected many types of crypto-chert that exhibit the characteristics of the igneous rocks described as agate and jasper, not to mention the hard siliceous qualities of the sedimentary and metamorphic rocks known as BIFs. Despite their ancient origins, these BIF specimens with bold bands of hematite take a high polish and can be displayed for their showstopping colors and patterns, as shown in photos in my previous article. My friend and Mingus Gem and Mineral Club colleague Mike Kavanagh has exhibited his artfully polished BIF specimens at our gem and mineral club shows.

Barrcano Agate Varieties Discovery

I learned about a particular variety of chert that was discovered near the Payson Municipal Airport by Carol Barr, a mining engineer, which the Arizona Geological Survey has examined. This nodular rock has been informally named “Barrcano Agate” in her honor. The specimen that was shown to Arizona Geological Survey (AZGS) has been classified as an agate, although some of the other orange-banded nodules among her sample collection are clearly an opaque variety that display characteristics of chert and jasper. Carol stated that AZGS gave it an average hardness of 7.2 on the Mohs scale.

The Payson area is well-known for its jasp-chert-agate deposits, especially since the Mogollon Rim is mainly an ancient chert-laden formation. Further discussion in this article covers the chalcedony cobble specimens from the same Payson collecting area that display attributes of agate, jasper, crystalline quartz and quartz druzy formations.

Since the Barrcano Agate has variable luster on exposed surfaces, it’s obvious that its many versions display attributes of all categories of common chert, and some jasp-agate features on the weathered-off surfaces. Since so many varieties of agate exhibit patterns along the weathered surfaces and within the rind and exterior faces, it’s common to initially find colors where they are easier to chip off and expose. These patterns were typically the first to form when agates develop within gas pockets of igneous rocks such as basalt, wherein silica solutions generate many band-forming layers as they adhere to irregular cavity surfaces. The patterns that appear in Barrcano Nodules are less developed and may have primarily formed in sedimentary rocks where mineral-bearing quartz solutions along bedding planes filled numerous spaces and voids.

Ancient life forms played an important role in creating biogenic silica and calcium carbonate in building up extensive nodular masses in sedimentary formations. Likewise, iron-oxidizing bacteria were an important source of banded iron formation. Such cementing mineral agents consolidated the Barrcano concretionary nodules as silica, iron oxide and calcite. These dense and compact float relics weathered out of their sedimentary host rocks and were found near the Payson Airport.

Since agate is commonly microscopically fibrous and translucent or semitransparent, I wanted to examine the mysterious nodular mineralogy. I asked Mike Kavanagh, our local gem show co-chairman, to cut a variety of slabs from the specimens Carol had collected for me. I made a few cabochons to determine the extent of mineral inclusions. I soon discovered that some of the nodules were only partially band-forming and translucent. I found inclusions of dense macro-quartz in the interior portions of many of these slabbed specimens so that concentric patterns only occurred on the exterior surfaces of the nodules. In most cases, the quartz interior zones are an opaque white-and-gray color, while in others, the quartz formations are large crystalline centers.

A small collection of the nodules and slabs do exhibit some jasp-agate and agatized constituents in the chert rocks.

Field Trip to Collect Iconic AZ Variety, “Zebra Stone”

Having recently collected varieties of black, brown and tan-banded chert in the Pine-Payson Mogollon Rimstone wilderness in 2018, I learned from the Mindat.org database that this version of chert (which was always referred to as “Zebra Stone” by our club members) is officially classified as an Arizona chert. The specimen shown on Mindat has the look of a high-quality jasper or jasperoid mineral. Considering the lustrous banded appearance of the Mindat type-specimen, one has to look harder at definitions of chert and jasper, as the Zebra Stone from this area can be both sedimentary and igneous in texture and appearance.

The third edition of my Dictionary of Geological Terms, of the American Geological Institute, by Editors Robert L. Bates and Julia A. Jackson, define “Jasper” as “1. a variety of chert associated with iron ores and containing iron-oxide impurities that give it various colors, especially red; and 2. Any red chert or chalcedony irrespective of associated iron ore. Synonym: jasperoid.”

The authors further define “Jasperoid”, another noun, on the same page, as “1. A dense, chertlike siliceous rock, in which chalcedony or cryptocrystalline quartz has replaced the carbonate minerals of limestone or dolomite; a silicified limestone.”

The Conversion of Silicification to Chertification

This definition of “Jasper” and “Jasperoid” clearly indicates the complexity of gradations that can occur in any one deposit of such material. After the Rim collecting trip, I brought my Zebra Stone specimens home to Sedona and laid them out in the sun to compare their characteristics. Some of the rocks have sedimentary attributes and are encased in a pure limestone matrix with little or no silica. Others are only slightly silicified in the banded areas and exhibit characteristics of ordinary sedimentary deposits. Still others, such as the Payson examples of Barrcano Agate and the pink and orange-banded jasp-chert we collected on our 2018 field trip contain higher levels of silicification. According to the same Dictionary of Geological Terms, “chertification” is defined as “Essentially silicification, especially by fine-grained quartz or chalcedony”. The term “chertification” contributes to my understanding of what it means to be able to identify chert-like rocks and their commonly associated minerals.

During our 2018 field trip, we also found specimens of orange and pink-banded Jasp-Chert along with boulder-sized masses of white botryoidal agate that resembled chalcedony roses. Some of the varieties of pink and tan jasperized nodules and fossiliferous cherty limestone rocks are part of the chalcedony-chert-sedimentary complex which is the subject of this article and representative of the North-Central Arizona mineral-rich complex of chert-infused deposits. This is definite proof of the cryptocrystalline characteristics of a type of chert that tends to morph into a harder more well-consolidated example of jasper or jasperoid, which I consider to be in a category above common chert and yet part of the constituent mineralization of the chert complex. The chalcedony-rich mineralization of this area is the source of this complexity in the quartz-suffused chert of the Mogollon Rimstone.

Many BIF deposits, especially those found in Minnesota and Michigan, are mined for their

concentrations of iron ore, some of these having been named “Jaspelite” for their iron-rich content and bands of hematite and quartz that are common in banded iron rocks.

Due to the extreme antiquity of these Precambrian deposits, which were originally sedimentary in character, almost all BIF formations have undergone some degree of tectonic transformation, deformation, and/or mineral alteration, whether due to contact metamorphism, which is a reconstitution of rocks that occurs at or near their contact with a body of igneous rocks, or contact metasomatism. Mindat.org defines the term “Contact Metasomatism” as follows: “A mass change in the composition of rocks in contact with an invading magma, from which fluid constituents are carried out to combine with some of the country-rock constituents to form a new suite of minerals.”

It is undoubtedly the case that BIF deposits as old as those in the Verde Valley, which were metamorphosed at 1.75 billion years ago, were altered at great depth below the surface zones of consolidation, cementation and erosion, which differ from the conditions under which the same rocks originated.

Fossil Forms Create Paleozoic Panoramas

What is especially interesting to me as a fossil collector in the Verde Valley is that chert most conspicuously occurs as nodular or concretionary formations in the regional sedimentary rocks. This unique circumstance has made fossil collecting on the Mogollon Rim and elsewhere in the Verde Valley an adventure for me.

My yard rocks evoke an ancient seafloor vista where reef-building relics pop up everywhere. I have a collection of well-preserved brachiopods. My sponge fossils are distinctive for their silica-infused spicule patterns. Some featureless coral fragments with reef-like shapes are the product of an extensive chertification process.

Chert nodules occur as extremely dense structureless masses within limestone and dolomite. I was curious as to why the features of some of the nodular and concretionary fossils had been erased. In my research, I learned that the silica-secreting organisms were frequently dissolved by fluids flowing through the rocks during diagenesis, prior to final lithification of mineral constituents. As a result, fossil formation is absent due to the complete dissolution of their organic debris over millions of years of depositional activity. And yet, despite the lack of fossil residue, the colonial animal forms were cast in stone like the victims of Pompeii.

Several of my knobby fossils from the Rimstone rocks are exactly the same type of hardened masses. These irregular mounds became recrystallized calcareous fossil concentrations of siliceous reef structures in Paleozoic seas. The once-thriving ecosystems were compacted by endless cycles of chert-enriched sediments fed by mineral laden silica solutions along permeable bedding planes.

The limestone-jasp-chert outcrops of the Mogollon Rim are among the most mysterious mixtures of sedimentary and igneous minerals.

Having accumulated a yard full of concretionary chert nodules from the Verde Valley where I live, it seemed natural to contemplate these extraordinary wonders of a lost world. The most intriguing collectibles recall the sedentary filter-feeders that built limey frameworks layered with chert minerals. Now my mother rock treasures have a new life as conspicuous curiosities in my red rock washes, retaining wall gardens, and landscaped planters.

Becky Solon is a retired U.S. Army Mechanical Engineer, MBA graduate and a mineral collector with training and interest in jewelry design.

REFERENCES:

1.

AZGS Contributed Report CR-09-B, 416 W. Congress St. #100, Tucson, AZ, 2009, “Limestone Discovery in the McDowell Sonoran Preserve, by Brian Gootee, Dan Gruber, Larry Levy, Joni Millavec and Bill Ruppert

2.

Geological Survey Professional Paper 233-D, USG Printing Office, Washington: 1952, “Devonian and Mississippian Rocks of Central Arizona, by John W. Huddle and Ernest Dobrovolny

3.

Dictionary of Geological Terms, Third Edition, American Geological Institute, 1984, by Robert L. Bates, Julia A. Jackson, Editors

4.

Arizona Banded Chert Specimen reference from the Mindat.org database: https://www.mindat.org/locentries.php?m=994&p=3293

5. http://www.galleries.com/rocks/bif.htm

6.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/usageology/47116425862/in/photostream/.