Mines with words and terms like Exodus, Lovely Lucy, Golden Dream, Shiloh and Never Sweat might seem unrelated, yet they do have one thing in common. All are names of mining claims that were staked in the late 1800s under the authority of what is familiarly known as the “1872 Mining Law.”

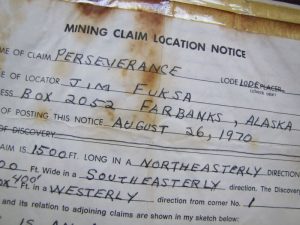

When prospectors recorded their mining claims, they were free to name these claims as they wished—within, of course, the limits of decency and district repetition. For many, naming claims was simply a recording technicality that warranted little time and thought. Accordingly, most of the one million mining claims that were staked in the West between 1872 and 1900 were predictably named after their owners, nearby communities, or local topographical or geological features.

But for some prospectors, naming claims was an opportunity to exercise creativity, imagination and personal expression. The names of these claims speak of human emotions, memories, faraway homes, everyday pleasures, wives and sweethearts, loneliness, grand expectations, bitter disappointments—even war. Together, they provide a telling glimpse into life in the frontier mining regions.

Mines Equal Boundless Hope and Lots of Luck (Sometimes)

Along with picks, gold pans and a rudimentary knowledge of surface geology, frontier-era prospectors also needed boundless hope, physical and mental strength, perseverance, tolerance for deprivation and a gambler’s confidence. The odds of striking it rich were stacked heavily against them; only a fraction of all claims ever became mines and few of those ever turned a profit.

Despite the odds, the names of many claims such as Paymaster, Quick Payoff and Good Wages reflected unbridled optimism and expectations of an imminent payday. Names based on currency and coinage were equally common: Silver Dollar, Greenback Dollar, Silver Certificate and Double Eagle.

Claims such as Royal Flush, Four Aces and Pair of Jacks were likely named by prospectors who were gamblers or who at least occasionally enjoyed a good game of poker.

Of all place names, “California” appears most often. Prospectors, apparently believing that invoking that word, synonymous with wealth and good fortune, might bring a little luck, gave us claim names like Little California, Son of California and Bank of California.

In their quest for good luck, some prospectors favored a more direct approach and used the word in claims like Good Luck, Lucky Strike, Dutchman’s Luck and Lucky Day.

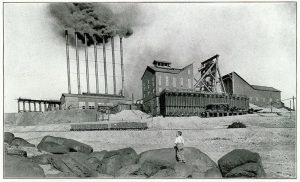

(Wikimedia Commons)

Tobacco, Whiskey and the Bible

In the rough mining districts, men and women found pleasure and sustenance wherever they could—often in tobacco, whiskey and the Bible. Claims like the Big Kick and Union Workman both refer to Scotten, Dillon Company’s two brands of chewing tobacco. In the 1890s, dozens of Beech-Nut claims testify to the popularity of Lorillard’s chewing tobacco; a decade later, Pinkerton’s Red Man Chew inspired an abundance of Red Man claims. But it was W. T. Blackwell & Company’s legendary chewing tobacco that appears most frequently in claim names— Bull Durham.

Other common claim names—Mountain Howitzer, Coffin Varnish and Tangleleg—were all period slang for whiskey. But unlike tobacco, the era’s leading whiskey brands—Old Overholt, Jim Beam, and Jack Daniel’s—are conspicuously absent from claim registries, perhaps because these brands were typically watered down, rebottled and privately labeled before reaching the mining districts.

Claim names like Sweet Jesus, Exodus and Judgement Day show that prospectors sometimes turned to the Bible, likely in hopes of beseeching good fortune from Providence. Several Please Lord claims hint of desperation and turning to prayer to better the odds of striking pay dirt. And, interestingly, a group of Pontius Pilate claims was located on Colorado’s Mount of the Holy Cross.

Particularly numerous were King Solomon claims, which initially referenced the wealthy biblical king. But after 1885, some similarly named claims were inspired by British author J. Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines, an adventure novel about a lost African diamond mine that greatly appealed to readers in the American West.

(Steve Voynick)

Memories

Most prospectors in the frontier West were far from home, and a hint of homesickness echoes from claim names like Georgia Farm, Hoosier, Shenandoah and Tarheel.

Prospectors who were Civil War veterans sometimes named their claims for battlefields: Shiloh, Bull Run, Chattanooga, Vicksburg and Chickamauga. Others remembered those they had served under in claims like Robert E. Lee, J. E. B. Stuart, Stonewall Jackson and Longstreet. The preponderance of Confederacy-related names indicates that, unlike most Union soldiers, many Johnny Rebs, with no homes or prospects to return to in the South, had headed West to seek their fortunes.

Claims named for women are particularly numerous. Since men filed most claims, these names are likely those of wives, mothers, sisters or sweethearts who did not often join them in the mining districts. Claims like Anna, Emma, Etta and Alice, and embellished versions like Sweet Betsy and Lovely Lucy, suggest loneliness among the men who staked them.

(Wikimedia Commons)

Songs, Poetry, Literature and Mythology

That prospectors had varying degrees of literary awareness is evident in claim names like The Raven and Eldorado, both inspired by the poems of Edgar Allen Poe. “Eldorado” was originally the Spanish vision of a mythical land of gold. But Poe’s poem of the same name, written during the California gold rush, tells of a gold-seeking knight whom a spirit encourages to never stop searching—certainly an inspiration for many prospectors.

Mining-claim names like Light Brigade are a nod to Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s “The Charge of the Light Brigade.” An Ancient Mariner claim recalls Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” while numerous Hiawatha claims were inspired by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem about a fictional Ojibwe warrior.

Claims were also names for popular songs. After the comic ballad “Oh My Darling Clementine” caught on in the California goldfields in the 1880s, Clementine claims suddenly began appearing regularly in the claim registries. The Yellow Rose of Texas, a song of the 1850s, also inspired many claim names. But songwriter Stephen Foster made the biggest impact; the many Oh Susanna and My Old Kentucky Home claims names came from two of Foster’s best-known songs.

And some prospectors drew upon mythology and history. The many Golden Fleece and Golden Horde claims were named, respectively, for the golden-wooled, winged ram of Greek mythology and the Mongol Empire that ruled parts of Russia and eastern Europe during the 14th century.

(Steve Voynick)

Naming Mines

Most mines were named after their original claims, but once mines showed real promise, owners often renamed them to suggest power, wealth and authority. And for good reason. Mine development required substantial capital and prospective investors would certainly show more interest in a Golden Wonder Mine than a Poverty Flats Mine. Hence, we have mine names like Independence, Vindicator, Invincible and Pride of America, all of which were developed from original claims with far less imposing names.

But a few major mines did keep their peculiar claim names. In 1888, a Butte, Montana, miner recorded his claim despite never having found any ore. When asked for his claim’s name, the despondent miner answered, “It doesn’t deserve a name, because I’ll never sweat bringing ore out of that worthless hole.” The recorder replied, “Well, I’ve got to name it something, so let’s call it the ‘Never Sweat.’” The Never Sweat Mine, despite its initial absence of ore, went on to yield a fortune in silver and copper.

Many believe that Colorado’s Matchless Mine, a bonanza property of Leadville silver baron H. A. W. Tabor, is named for its “matchless” grade of silver ore. But the name actually refers to Lorillard’s Matchless Chewing Tobacco.

The Last Chance Mine in Creede, Colorado, now a popular tourist mine, is also named for its original claims. These were staked on the end of the four-mile-long, silver-rich amethyst vein which, geologically speaking, was indeed the “last chance” to strike it rich.

(Steve Voynick)

Fuel for the Imagination

Virtually no documentation exists to explain exactly why mining claims received their names. But it’s fun to guess at the stories behind names like Jumping Jackass, Smith & Wesson, Tough Nut, Wake Up Jim and Borracho (Spanish for “drunk”).

The word “lost” made it into many claim names: Lost Horse, Lost Rifle, Lost Treasure, and, perhaps most curiously, Lost Partner. But the most common words in all claim names are, not surprisingly, “gold” and “golden.” In California alone, these words are found in more than 2,000 claim names. Along with the expected Gold King and Gold Queen claims are such whimsical names as Golden Loser, No Gold and, my favorite, Golden Pickle.

Finally, claims like Tin Cup, Coffee Pot, Dinner Plate, Salt Pork and Bean Kettle imply that, while prospectors may have wandered far from home, their thoughts never wandered far from the dinner table.

Of the thousands of new claims currently staked each year in the West, most receive mundane, matter-of-fact names to satisfy recordation requirements. But some are christened with imaginative and colorful names to reflect the frontier spirit that still survives in the uniquely American experience of staking a claim.

The “1872 Mining Law”The legislation that authorized mineral claiming and subsequently shaped much of the West was the General Mining Act of May 10, 1872, defined as “An Act to Promote the Development of the Mining Resources of the United States.” This Act combined traditional mining policies with such new concepts as a patenting provision to enable claimants to take full title to their claim and a “free-mineral” policy that exempted federal royalties on mineral production. As an enticement to populate and develop the West, the Mining Law exceeded all expectations. By 1900, it had encouraged countless men and women to risk their time, effort, personal resources, and sometimes even their lives to search the public domain for minerals. In doing so, they staked 1.2 million claims, settled much of the West, built an industry, and made the term “stake a claim” an enduring part of the American vernacular with meanings that now far supersede its original mining context. But the Mining Law is not without controversy. Today, supporters call it a time-honored manifestation of the American frontier spirit and the foundation of the West’s mining economy, while detractors argue that it is a costly, archaic law that disregards modern concepts of environmental protection and public-land use. Since its enactment 152 years ago, prospectors have staked more than four million claims, of which 422,500 are active today. Although the law’s scope and authority have since been radically reduced, its basic procedures for staking and recording claims are essentially unchanged, and several thousand new claims are staked—and named each year. |

This story about claiming & naming mines appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Steve Voynick.