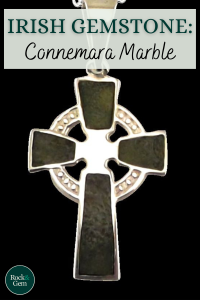

Connemara marble is one of the rarest of marbles in the world. Nestled in a tiny region located on Ireland’s west coast is the district of Connemara. Its landscape weaves a tapestry of mountains, heathlands, bogs, and lakes. A handful of marble quarries dot the landscape and harbor the 900 million-year-old carboniferous limestone. It was once used to construct grand palaces, government buildings, and schools. Today it’s primarily fashioned into jewelry and souvenirs.

A Heritage Stone

In 2022, Connemara marble was designated a Heritage Stone — one of only 32 Heritage Stones worldwide. The designation is made by the International Union of Geological Sciences.

“Its rarity makes it pricey so it’s usually used to make small items such as broaches, earrings, figurines or accessories that are designed to slip easily into the suitcase or carry-on luggage of a tourist,” wrote Roisin Murphy in The Irish Independent. “Lately, however, bigger options have been Courtesy of J.C. Walsh & Sons appearing – coasters and cheeseboards, beautiful simple bowls – and they give a better idea of the extraordinary depth of the colors in the stone. It looks as if something moving was frozen. Unlike Carrara marble, its smoky and neutral-colored Italian cousin, the Irish stone is like an alien liquid or gas trapped behind glass.”

Connemara Through History

The word Connemara comes from Gaelic for “Inlets for the Sea.” It is mined in an area that is only 20 miles long from east to west, running north of Galway to Clifden and a mere quarter mile wide from north to south.

Prehistoric beads and axe heads made from Connemara marble have been discovered and are now preserved in museums. The marble decorates the halls and recesses of famous spaces including Kensington Palace, Westminster Cathedral, London’s General Post office, the National History Museum in Oxford, the State Capital Building in Pennsylvania and the Gould Memorial Library in the Bronx. The architectural firm of McKim, Mead, & White, founded in 1872, helped the stone gain notice.

How Connemara Marble Forms

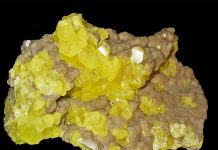

What makes Connemara marble, a calcite marble, distinctive is its geological location and the way it formed.

“As the various layers were formed in between 900 million and 600 million years ago, the different minerals and materials were layered down like a packet of dry lasagna,” said Stephen Walsh, a Connemara marble historian, and spokesperson for J.C. Walsh & Sons. “During the Grampian era, as the mountains were being built, those layers were compressed and the limestones heated and metaphorized into a marble.”

The layers are compacted with substances including seaweed, sand and silica. Serpentine gives the stone the deep jewel-green hue that’s become its hallmark. The presence of epidote accounts for paler green shades; calcite adds the misty gray tints; pyrite allows for a touch of gold to be seen in some pieces, while phlogopite, a common member of the mica mineral group, adds a glimmer of bronze color.

Mining Connemara Marble

Several methods have been used to remove the marble from the earth. Picking or scavenging entails lifting or chipping away at loose stones. It’s tedious work, but in some cases, can yield results. In the 19th century, line drilling, also called plugging and feathering, was employed.

“This method calls for the drilling of vertical, closely spaced holes along a line where a block is to be extracted from the quarry face,” Walsh explained. “Steel wedges or ‘plugs’ are put into each hole and two steel wedges, or ‘feathers,’ placed on either side of the plug. By tapping these plugs, one by one, along the line of the holes, the pressure gradually builds up and the block will break evenly along the line of the holes.”

In the mid-19th century, dynamite was brought into the quarries. While it helped loosen large blocks of marble, below ground, it created shock waves that led to hairline fractures in the stone. The wire saw of the late 19th century proved more efficient in removing the marble. Today, steel wire is fitted with diamond beads that allow for a more precise cut.

Walsh said despite the rarity of the marble, most of it doesn’t end up in the hands of the consumer.

“If we take out a ton of marble —1,000 kilos — we will only get 100 kilos of finished material. We have a 90 percent waste factor because the color isn’t green, there could be an imperfection or one of those striations is just weak and it’ll snap,” explained Walsh.

Connemara Marble’s Legacy

Connemara marble is alluring to people who love its diverse shades of green and those who are fascinated with its ancient roots. The stone is popular with tourists and those with Irish or Catholic roots. Walsh’s company has sold more than 160,000 rosaries on QVC, for instance.

“It equates to over 100 miles of rosaries end to end. There are 50 Hail Marys on each rosary — that’s eight million Hail Marys,” he said with a laugh. “It’s been a wonderful way to reach a wide audience. You have that touchstone back to where your ancestors came from and I think that’s something magical.”

Connemara Marble Quarries

The three workable quarries for Connemara marble are located at Lissoughter, Streamstown, and Barnanoraun, with other locales inaccessible underwater.

Lissoughter Quarry

First owned by the Martin family, the quarry at Lissoughter opened in the 1820s. What made removing marble from Lissoughter easier than at the other sites is this quarry is above ground and on a hillside, which allows it to avoid flooding. Lissoughter Quarry took part in the building boom of that time.

“In 1820, Ireland was owned by England and there was this huge building boom going on — incredible Romanesque style buildings,” said Walsh. “English architects were sent out to their colonies to look for decorative marbles to be used in these great houses. They found themselves in Connemara eventually.”

In 1903, King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra visited the quarry and in 1922, the Republic of Ireland was established. As changes in building materials took place and World Wars were waged demand decreased.

“Around the 1920s, demand for Connemara marble basically dried up. The quarry was more or less abandoned and the other two quarries in the area were pretty well abandoned. The only thing that was really happening were maybe a little bit of souvenirs,” said Walsh.

Owning Lissoughter Quarry

According to Walsh, in November 1945, his grandfather and a few friends formed The Irish Consolidated Bead Company to produce rosary beads for the Irish and overseas markets. It was based in a small workshop in Terenure Place, Dublin. “My father, John, joined the company in November 1954 and under his management, the business flourished. I joined the company in 1975, right after leaving school, and quickly learned the business.”

As demand for Connemara marble and Irish jewelry began to increase, Walsh searched for a permanent source of the marble. Lissoughter was dormant at the time Walsh bought it in 1983.

“I literally went out on safari to Connemara, armed with my hammer and my Boy Scout compass…With the help of the Geological Survey of Ireland, I got some maps and found a site that had not been worked for 50 years and more. It was like finding Sleeping Beauty’s castle,” he explained.

Connemara marble turns black over time due to oxidation and is not ideal for outdoor building projects.

“There were all these kinds of blackened stones laying around (when the quarry was reopened),” he said.

A partnership with the home shopping channel QVC in the late 1980s helped propel the name Connemara marble across the Atlantic, debuting on St. Patrick’s Day in 1990. Walsh started appearing annually on air with the network in 1993, flying to QVC’s Pennsylvania-based studio to participate in live broadcasts. He continues to do so remotely.

Streamstown Quarry

The quarry at Streamstown saw a great deal of marble extraction in the 19th and 20th centuries. The marble there is known for possessing a rich patterned green and a brownish-white, known as sepia marble. This marble can be viewed in the church of Saints Peter and Paul in Athlone (interior columns) and on the floor in Galway Cathedral.

Walsh said that because of innovative methods employed by its owners, this quarry endured as others closed down.

“The owner of the quarry was Terence Bourke, the 10th Earl of Mayo, and his company, Marble Panels Ltd., produced many marble pieces for the home and export trade. In fact, almost all large pieces of Connemara marble from the mid-20th century came from this quarry, and this kept the ‘brand’ alive,” Walsh explained in his book, Connemara Marble: Ireland’s National Gem.

Using the terrazzo method, Bourke produced durable floor tiles. He also used the quadrilateral symmetry technique which entailed cutting a large block of marble into slices and putting the cut slabs together to create a kaleidoscope or butterfly pattern. His special lightweight marble panels were installed in luxury jets, yachts, and cruise ships.

The quarry was deserted for many years and then taken over by Ambrose Joyce. The family operates the Connemara Marble Visitor Centre in Moycullen.

Barnanoraun Quarry

Barnanoraun once belonged to the Martin estate. Marble from this area is a rich green and yellow shade with fine patterning. Thomas Martin opened the quarry in the early 19th century. The family also built the famous Ballynahinch Castle, which is today operated as a luxury hotel. The estate endured financial hardship during the Great Potato Famine and went on the market in 1849. It was eventually sold to Richard Berridge in 1872.

Walsh notes that the Berridges owned the Barnanoraun and Lissoughter quarries until the 1960s. Michael Joyce then bought both quarries and ran a marble workshop at the former Recess hotel. His son Kevin later pursued large-dimensional stone development for buildings.

This story about Connemara marble appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Sara Jordan-Heintz.