By Bob Jones

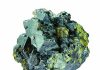

One of the most beautiful minerals we can own is crocoite, a bright red lead chromate. It is also one of the more fragile minerals to mine, handle and own. But its vibrant orange-red color and long slender crystals in elongate, striated, reticulated aggregates rival just about any other mineral for display appeal.

Fragile and Fanciful Mineral

Crocoite was first found in the Ural Mountains of Czarist Russia. Its discovery was made when gold was found in abundance within the middle Urals in about 1745. Crocoite was first found in the Tsvetnoi mine in the Uspenska Mountains, on the east side of the Urals about 1766. The nearest settlement of note to the discovery was Berescov or Beresovsk, Sverdlovsk Oblast not far from Ekaterinberg. Note it is not unusual in Russia for a locality to have more than one name and Beresov is no exception. The place has had its name changed a couple of dozen times.

The vibrant red mineral once found in modest crystals seldom over an inch in length was quickly given the name red lead or Siberian Red Lead. Specimens of the mineral were set to Paris for study, where Louis Nicolas Vauquelin and another scientist worked on the mineral but mistakenly reported that it contained aluminum. Vauquelin was not satisfied with the results, and in 1797 began a long and tedious experiment to isolate the mineral’s contents.

It took more than a year, but in 1798 Vauquelin did prove that Siberian Red Lead contained a new metal element he named chromium. We now know this element as the shiny metal on chrome goods and as one of the most active transition metal elements that causes colors in some gems and minerals.

The Beresovsk deposits are considered the type locality for crocoite and also designated the locality that produced the mineral that was used to prove chromium as a new, discrete metal element. It is unfortunate that these Uralian mines are also where, in 1917, Russia’s ruling Czar and his family met their death.

Crocoite Found In Gold Mines

A large number of the gold mines in this Russian area produced crocoite but never in sufficient quantities to satisfy mineral collectors’ wishes. Fortunately, this deficiency was remedied when it was discovered in Tasmania, in an area that at the time was a prison colony, in the middle 1800s. This resulted in a concerted prospecting effort, and slowly other deposits of tin as well as silver and lead were found. In the area known as Dundas, which was very remote, lead deposits were found, and eventually amounts of red lead were encountered.

By the 1790s, crocoite began showing up in quantity. It was never a significant ore of lead, but specimens were recovered to supplement the Russia crocoite supply. When lead and silver mining in the Dundas area ceased, so did the supply of crocoite, and the area slowly deteriorated and was abandoned. Things remained as such until the 1950s, when specimen collectors began searching the Dundas area.

Largely credited with persistently searching for and finding crocoite was a fellow named Frank Mihelowitts. Frank began collecting and selling crocoite to such a degree that he eventually was given the name “Mr. Crocoite” by major Australian collectors like Albert “Chappie” Chapman. Chappie, a delightful gent and perhaps the most active mineral collector in Australia, was a regular in the early days of the Tucson Show®. On a visit to Australia, I was able to see Chappie’s collection on display in a small museum at “The Rocks,” which is a shore-side landing in Sydney harbor where convicts were off-loaded from England in the old days.

A steady but minimal flow of crocoite continued from Tasmania after the 1950s and 1960s. Recently, the flow has become a virtual flood thanks to a team of rockhounds who have banded together to explore and mine red lead specimens. Their Trojan effort has brought to light an amazing supply of gorgeous, bright red crocoite, a supply that seems almost endless.

Converging on Tasmania

With renewed interest in the Tasmanian sources of

crocoite, after 1960 more prospectors explored and mined the old lead mines and brought fine crocoite specimens to market. Mines with names like Dundas Extended, Red Lead, West Comet, Platt, and Adelaide began proving fruitful.

Among these mines, it’s the Adelaide mine where two remarkable finds of crocoite took place, first in the 1970s and again in the last 10 years. In 2010 and 2012, astounding pockets of crocoite were discovered and mined for specimens. Doubly exciting is the effort made to document these finds and the removal of quantities of specimens.

The 1972 find of a crocoite pocket was, at the time, the largest find ever reported from Tasmania. Large pockets had undoubtedly been encountered during active ore mining full-time but remained unreported. The 1972 find was reported by a miner who was specifically searching for crystals. This pocket, described as being completely lined with crystals, is reported to have extended 8 feet deep, 6 feet high, and more than 4 feet wide. The walls of the pocket from top to bottom were completely covered with bright, orange-red, toothpick-sized crystals of varying lengths of the red lead mineral.

Intricate Specimen Examination

If you have ever examined crocoite specimens closely, you know the bright orange red crystals are very delicate, often actually hollow, seldom well-terminated, and exhibiting a nearly square cross section. They are easily broken because of the thin crystal walls. Crocoite is a secondary mineral formed when chromium ions and lead ions bring forth the mineral. Luckily, the crystals develop on weathered limonite, so they generally occur resting on a fairly soft and badly weathered matrix. This may present a problem for collectors since a badly weathered matrix means specimens may not hold together once collected. This can be stabilized by soaking the matrix, not the crocoite, in a white glue water solution. But often a fragile mineral like crocoite having a relatively soft matrix is a blessing.

If the crocoite had occurred on a very hard, tough matrix the problem of collecting undamaged specimens would be grossly more difficult. With fragile crocoite, a soft matrix is a benefit to specimen collectors, though they have to devise the right methods needed to collect intact specimens. The use of heavy hammers and chisels is out, as such vibrating action would destroy the crystals.

This was the circumstance of the 1972 pocket when it was discovered. It presented the miners with the dilemma of rescuing the fragile crocoite intact! Unfortunately, back in those days, collectors used the tools available, so mining the 1972 pocket caused a considerable loss of the specimens they were trying to save. Today that would not happen thanks to a new technique devised by miners working a discovery made in 2010.

Powering Up To Cut

I’ve seen examples of trying to collect fragile or unstable minerals that would suffer much loss if not done right. In one case, my son and his partner found a very fine, 6-inch pocket of bright orange-red wulfenite and mimetite in a virtually solid rock matrix.

The problem was solved by using power equipment to cut into the rock a foot or so away from the pocket. By removing a huge, nearly 60-pound section of wall containing the fragile wulfenite pocket, it survived for later careful trimming. Luckily, we now have diamond saws and other modern tools to cut away the matrix without disturbing fragile crystals.

Another technique used was applied to an open vein of vanadinite in Arizona’s Grey Horse mine. These vanadinite crystals were loosely attached to the matrix. Instead of hammering away, the miners covered the specimens with water-soluble white glue, successfully removed the specimens, then soaked off the glue. Large specimens of vanadinite were extracted and now reside in a faux-pocket in the Arizona Sonora Desert Museum near Tucson.

The 2010 and 2012 discoveries at the Adelaide mine were very successful because the miners thought outside the box and used techniques to carefully extract quantities of specimens. This was done by removing entire sections of wall completely covered with bright red-orange delicate crystals.

Open Vein Delivers Treasures

The 2012 find was a huge open vein that measured several feet wide. It was so deep that when a video camera zoomed in to capture the back side of the pocket, it could not reach it because sections of wall were in the way and the light could not illuminate the deepest reaches of the vein. As an open vein, the walls extended out of sight upwards as well. The entire open vein, too big to be called a pocket, was completely lined with crocoite crystals ranging in size from under an inch or so to 4 and 5 inches long, with a few measuring even longer.

With great care and skill, the miners carefully loosened and removed entire sections of wall weighing well over 100 pounds and several feet long or more, without breaking or losing the delicate crystals that completely covered the wall section. Such large pieces were later worked on carefully to extract specimens of all sizes, each of which was generously endowed with fine crocoite crystal clusters.

Recovery of specimens and keeping breakage to a minimum was a very difficult challenge. But the miners rose to the challenge. They solved the problem and recovered an amazing percentage of the crocoite when they realized the matrix was soft enough to be cut with a saw and not split with steel chisels.

The crew responsible for recovering a huge quantity of crocoite at the Adelaide mine included Bruce Stark, Adam Wright, and Bruce Bottril. They were joined by one of this country’s most accomplished and successful specimen miners, a fellow whom I admire for his specimen mining skills, John Cornish. Together this crew worked successfully to extract huge quantities of crocoite, with a much lower percentage of specimen loss than anyone expected. Working carefully in what they called the crocoite or crystal cave, which it really was, they did a masterful job of saving this beautiful mineral. The crystal cave was officially called the Red River find. No matter the name, it was the find of a lifetime.

Exploring Mining Techniques

The mining technique the specimen crew developed fit the circumstances of the occurrence. The crocoite crystals had formed on a relatively soft matrix composed mainly of very badly weathered limonite, probably derived from the breakdown of pyrite. Knowing they could not and indeed did not need to use a hammer and chisel, the miners hit upon the solution. The matrix was soft enough to be cut using an ordinary hand saw designed for cutting lumber.

To this writer, the most exciting thing about this crocoite

project, since I could not be there, was to watch the mining of specimens firsthand, thanks to Bryan Swoboda, Bluecap Crystal cave, as the miners extracted specimens including removal of a huge section of crocoite-covered wall! It’s as if you are right there watching the action.

You can get the DVD “The Adelaide Mine” from www.bluecapproduction.com or wwadelaidemine.com. You’ll love it!