Editor’s Note: This is one of 10 Mexican locales recognized for mineral production. View the rest of the list as featured in an article by Peter Megaw>>>

The bustling northern industrial city of Chihuahua owes its origin to the fact that it lies at the closest source of water to the enormous mines of Santa Eulalia, which lie just 22 kilometers to the east. Like Ojuela, mining began at Santa Eulalia during the Spanish Colonial era, but unlike Ojuela, formal commercial mining continues today.

Santa Eulalia is the world’s largest example of a Carbonate Replacement Deposit (Ojuela, San Pedro Corralitos, and Los Lamentos are others) and has produced more than 500 million ounces of silver from ores averaging 10 ounces silver per ton, 8% lead, and 7% zinc (Megaw, 2018). Santa Eulalia’s major mines lie on opposite flanks of a north-south elongate mountain with the Potosi and Buena Tierra mines dominating the West Camp and the San Antonio mine dominating the East Camp. The camps are separated by about 4 km as the crow flies. The West Camp mines are mostly dormant now, although the Potosi mine was active from 2013 to 2014. The San Antonio mine remains active, producing about 1,000 tons of ore per day.

Examining Santa Eulalia’s Ores

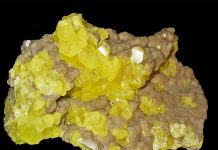

Prior to the 1930s, the bulk of Santa Eulalia’s ores were oxidized silver-lead ores originally found in outcrop and then followed laterally for more than 4 kilometers underground. These ores developed over the eons as infiltrating surface waters oxidized enormous bodies of massive sulfide ores composed of galena, sphalerite, and pyrrhotite.

The bodies were so large and continued to such great depths that their deeper reaches

were unoxidized and provided huge tonnages of sulfide ores for more modern mining. Although Santa Eulalia’s West Camp mines have produced quantities of colorful mimetite and wulfenite from their oxide zones, blinding white hemimorphite crystals to 4 inches in singles, fans, and balls are more famous because of how many have been produced.

The West Camp’s fame for color comes mostly from the deeper unoxidized orebodies that have produced lilac to purple creedite as balls and single crystals to 6 cm and a huge array of rhodochrosite ranging from pink botryoidal masses to gemmy blood red crystals to 6 cm in length (Jones, 2008). Rhodochrosite also occurs as microcrystals showing a wide range of forms and habits, commonly associated with crystrallographically complex limpid fluorites and rarer red hübnerite and gemmy orange natanite.

The has also produced abundant robust white hemimorphite groups but is much more famous for smithsonite in colors ranging from yellow to green to an intense blue that rivals the famous Kelly Mine of New Mexico. The smithsonite zone also produces pseudomorphs after scalenohedral calcite crystals up to 5 cm long. Smithsonite production is intermittent and depends on water inflows in the deeper parts of the mine.

The limestones that host the San Antonio’s ores are laced with open, water-filled fractures that are routinely cemented off. Occasionally workings reach one before it can be cemented, bringing up to 90,000 gallons per minute into the mine and completely overwhelming the pumping infrastructure. When this happens, the mine floods quickly to the water table – where the smithsonite is found. Mining then focuses here until the inflows are plugged and the deep zones are pumped out for renewed mining. The mine’s headache is the collector’s joy!