Digging for amethyst stones in Morocco is an adventure worth sharing. People have been prospecting in Morocco for many years, so one might think that most mineral and fossil sites would be well known. However, major new finds of both fossils and minerals continue to be made.

Traveling in Morocco

I traveled to Morocco several times over the last two decades, where I visited a few of that country’s many fossil and mineral localities. Most of these localities are quite famous, such as the vanadinite mines near Mibladene. A few days later on that same trip, I was able to visit a fascinating locality that was, in contrast, totally unknown. Until now.

All of my trips to Morocco have been arranged by tour leader, Sara Mount, of Silver Spring, MD. In Morocco, Sara works with brothers Adam and Aissa Aaronson. In addition to serving as tour guides, the Aaronson’s are dealers of fossils, minerals and meteorites.

They have developed connections with fossil and mineral miners all over Morocco. It is through their contacts that I have been able to see many of the geological riches of Morocco. Morocco is a safe country for Americans to visit and I have never felt threatened in any way. Comfortable accommodations and good food are widely available. I have never had to rough it, aside from day trips like the one described below.

A New Amethyst Stones Locality

The new locality I visited is an amethyst deposit in the Anti-Atlas Mountains. Amethyst has been known in Morocco for many years, but the new site has the potential of greatly increasing production.

Amethyst is found in a small percentage of geodes that occur in the High Atlas Mountains. In recent years, amethyst crystals with hourglass zonation have been coming from a place called Tata, in southern Morocco. Massive amethyst has also been found in eastern Morocco, near the Algerian border.

The Anti-Atlas Mountains

The Anti-Atlas Mountains are one of the four main mountain ranges of Morocco. The High Atlas Mountains, with peaks up to 13,671 feet, are the highest and bisect the entire country from southwest to northeast. To the northwest are the Middle Atlas Mountains. and, further north, the Rif Mountains. With peaks up to 10,841 feet, the Anti-Atlas Mountains lie to the southeast of, and run parallel to, the High Atlas. Further south and east begins the Sahara Desert.

The geology of the Anti-Atlas Mountains. is very interesting. A wide variety of formations is present. Much of the mountain range consists of igneous rocks of the late Precambrian age. Granite formations occur in some areas, along with metamorphic rocks, such as schists.

In many places, Paleozoic age sedimentary rocks are also found. Some of the sedimentary formations contain interesting fossils, particularly of trilobites. The Anti-Atlas Mountains are thought to have initially been formed in the late Paleozoic Era when plate tectonics caused Africa to collide with North America. The same collision resulted in the uplift of the Appalachian Mountains in North America. Further uplift occurred in the Cenozoic Era when Africa collided with Europe.

The climate of the Anti-Atlas Mountains is mostly quite arid. Vegetation is sparse, mostly low-growing herbaceous plants. The vegetation does support some grazing of goats, sheep, and camels. Rugged terrain and exposed rock formations give a certain stark beauty to much of the area.

The Unnamed Amethyst Locality

The new amethyst locality, as yet unnamed, lies about ten miles east of the city of Ouarzazate. The nearest named town is Tabount, which is a suburb of Ouarzazate. Not far away is Bou Azzer, where a fabulous array of cobalt and silver minerals is found. These minerals can be seen at several dealers in the area. Ouarzazate is also the center of Morocco’s thriving movie industry.

Moviemakers often go to Morocco when they want a safe place to film scenes set in the Middle East. Scenes from “Lawrence of Arabia,” “Gladiator,” and “The Last Temptation of Christ,” for example, were shot in the area.

The amethyst deposit is on the side of a hill at an elevation of about 4000 feet. The rocks in this area consist primarily of volcanic rocks of late Precambrian age. Much of the country-rock consists of breccia. These are igneous rocks that were shattered by later volcanic eruptions and then cemented back together. Also, present are porphyries and other igneous rocks. The amethyst deposit consists of large quartz veins cutting through the breccia.

Besides amethyst, there is also copper mineralization in the area. These deposits appear to consist of copper sulfides, possibly chalcocite, in quartz and their alteration products, such as malachite. Not far from the amethyst deposit there is a small, abandoned copper mine, dating back possibly to the 1950s or 1960s.

Checking Out the New Find

As mineral dealers, Adam and Aissa are always looking for new mining opportunities. Adam, for example, has mined industrial barite near Erfoud. Adam had heard of the new amethyst deposit from two prospectors, Lahrou and Hussain.

I had met Lahrou years ago and featured him prominently in my June 2020 article. He and his brother Hmad mine vanadinite near Mibladene, and serve as guides to other local mineral localities. When our group of travelers was in Ouarzazate, Adam wanted to check out the new find.

Several members of the group were going to tour a local movie studio that day. I, however, chose to accompany Adam to see the amethyst deposit. Also choosing to see the amethyst was Jim Cooper, a gemstone collector and travel enthusiast from Michigan, who has been on a number of these trips.

Adam drives a capable four-wheel-drive SUV, which would come in handy that day. The weather was sunny with temperatures probably in the 70s, typical for the season. After picking up Lahrou and Hussain, we headed out of town on a good two-lane paved road.

Soon, however, we turned off onto an unpaved dirt track, which was barely visible in spots. Passing the old copper mine, we followed the track for about three or four miles, until we couldn’t go any further. We then hiked a half-mile, or so, to the site. At first, we followed a dry creek bed, which was not too bad. Then, we started uphill. We passed one small area of copper mineralization, but there was not much of interest to be collected there. I’m not in as good shape as I used to be, and I was nearly out of breath. I was beginning to wonder if it was worth the hike. It was.

Finding Amethyst Stones

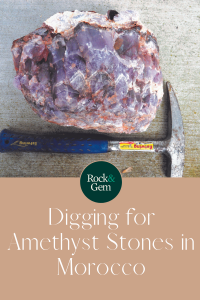

There was amethyst galore. The quartz vein is about a yard thick, and mostly solid amethyst. Hussain and Lahrou had dug up a section measuring 15 – 20 yards long and up to about six feet deep. Adam said that they had done this with only hand tools over the course of four working days, though not consecutively. He aptly describes them as “bulldozers.”

The vein is nearly vertical in the ground. The portion near the surface, down to perhaps a foot, is mostly white. Over time, exposure to sunlight will cause amethyst to fade to white quartz (Remember this when you are looking for a spot to display your prized amethyst specimens!). Exposure to the intense Moroccan sun for many years appears to have bleached out the near-surface portion of the vein. Below this layer, however, the vein is nearly all amethyst. In some areas, there are gaps in which terminated crystals had formed. In other areas, the vein appears to be solid amethyst.

Most of the amethyst is an attractive shade of medium lavender. Generally, there is no smoky caste that a lot of amethyst has. Much of the material has interesting white chevron banding. I did not see any material that was clean enough to facet, but much of it should make good cabochon material. After I got home, I polished a piece, which turned out nice. Larger chunks should make good decorative pieces, while smaller fragments should tumble polish nicely.

Mineral Specimens

The new site also promises to be a good source of mineral specimens. Terminated crystals are numerous. Most are in the two-to-three-inch range, but I found one about seven inches long by four inches across. In some areas, there were layers of amethyst several inches thick with terminations on one, or both, sides. I saw one small piece that had doubly terminated amethyst crystals.

Adam picked up a couple of pieces of amethyst associated with what appears to be botryoidal hematite. The purple color of amethyst is caused by iron, so the presence of hematite, an iron oxide, could explain the presence of amethyst instead of white quartz.

Jim and I were given free rein to collect. Hussain and Lahrou had dug out piles of amethyst, so there was not much need for the hammers that Adam had brought along. While Jim only took a few pieces, I soon had more than I could carry. Every time I thought “that’s enough,” I would find another piece that I could not pass up (Sound familiar?).

Bringing Amethyst Specimens Down the Mountain

Thankfully, Lahrou and Adam volunteered to carry some of it back to the car for me. Going down was in some ways harder than going up had been. I had to slowly pick my way down to the bottom of the hill, but from there the rest of the walk to the car was not bad. A good drink of water and an electrolyte tablet, and I was good to go.

Getting a pile of amethyst down from the site was one thing. Getting home with it was another. There was no way I could get on a plane with all of it, and mailing it back would have cost a small fortune.

Fortunately, Adam and Aissa are major fossil and mineral dealers. Their business is large enough that every year they send a shipping container full of fossils and other merchandise to Tucson. Adam graciously offered to send my amethyst along with his shipment.

Since I go to the Tucson shows every year, getting it home from there would be relatively simple. I thus cleaned and packed a few choice pieces in my suitcase, and let Adam take the rest. Unfortunately, when I was in Tucson, the shipment had not yet arrived. However, it arrived soon thereafter, and Adam was able to ship it me at a reasonable cost. Everything arrived safe and sound.

Much more exploration of the site will be needed to fully assess potential amethyst production. It is unknown how far the exposure extends on the surface, or how deep it goes. There is also at least one other vein that has not been excavated. The potential is there, however, for the site to become a major source of both specimens and lapidary material.

Adam indicated that he was interested in commencing mining of the new amethyst deposit, provided that someone else does not already own the mineral rights to the area. If someone still owns the rights to the old copper mine, for example, it could also include the area where the amethyst occurs. Adam says that Moroccan mining laws are complex, and it may take quite a while to sort it all out.

When I saw Adam a few months later in Tucson, he said that there had been little progress. Regardless, I feel fortunate to have been among the first people to see this new discovery. I wish Adam success in his pursuit of it and hope to see his amethyst on the market in the future.

This story about digging for amethyst stones appeared in the October 2021 issue of Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe! Story and photos by Bob Farrar.