Editor’s Note: This is the first of a two-part series about the mining of jade in Myanmar, formerly Burma. Be sure to enjoy Part II>>>

By Steve Voynick

In the 1990s, Richard Hughes was one of the first western gemologists and authors to visit Myanmar in three decades. After touring that nation’s jade mines and markets, he described the jade trade as “… a spin of the roulette wheel. Some will win, more still will lose.”

Since that time, the production and prices of Myanmar’s jade have soared to record highs. But one thing has not changed: just as Hughes noted, that nation’s jade trade still has only a few winners and many more losers.

The Hpakan region of the southeastern Asian nation of Myanmar (formerly Burma) produces the world’s finest jade. “Burmese jade,” the traditional name preferred by the gem trade, is known for its exquisite colors, translucency, and fine grain that are unmatched by jade from any other source.

Finished pieces of the finest Burmese jade now sell for thousands of dollars per gram, and recent mine recoveries have made international headlines. In 2015, a Hpakan mine discovered a 200-ton jade boulder worth $17 million. Two years later, miners found a 50-ton jade boulder worth $3 million. Despite their remarkable sizes and values, these two finds represent only a tiny fraction of Myanmar’s annual, multi-billion-dollar jade production.

The dark side of the story of Burmese jade, however, is one of rampant government corruption, environmentally disastrous open-pit mining operations, huge profits reaped only by a few wealthy mine owners, and thousands of artisanal miners trapped in an endless cycle of poverty, drug abuse, and dangerous labor.

UNDERSTANDING THE MINERALS OF THE JADE GEM

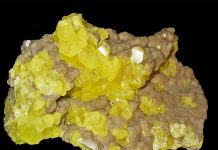

The gemological term “jade” pertains to two distinct minerals: jadeite and nephrite. The pyroxene mineral jadeite is a sodium aluminum iron silicate; nephrite, a basic calcium magnesium iron silicate, is a member of the actinolite-tremolite series of amphibole minerals.

As metamorphic minerals, jadeite and nephrite occur at subduction zones near convergent tectonic-plate boundaries. But because of differing pressure origins, they are not found together. Neither occurs pure. Both jadeite jade and nephrite jade are technically rocks. Jadeite jade consists primarily of the mineral jadeite, along with lesser amounts of albite, tremolite, aegerine, and augite. Nephrite consists mainly of intermediate members of the actinolite-tremolite series.

Both jades crystallize in the monoclinic system but usually occur only in compact or massive forms that have a splintery fracture and no cleavage. Jadeite is nearly as hard as quartz; nephrite is a bit softer. Jadeite’s specific gravity ranges between 3.3 and 3.5; nephrite is somewhat less dense. The colors of both jades vary widely, with green, lavender, white, and gray being the most common. The colors of jadeite jade tend to be more intense than those of nephrite jade.

While not particularly hard, both jades have an unusual texture that imparts extraordinary toughness and fracture-resistance. Under a scanning-electron microscope, they consist of tightly interlocked microscopic crystals and fibers.

When minerals and rocks fracture, mechanical energy travels in a trans-granular mode, progressing not around interlocked crystal grains but directly through them. Because jade’s grains are randomly aligned, an energy wave must change direction with every grain it encounters, thus requiring an unusual amount of mechanical energy to propagate a fracture.

JADE’S RELEVANCE ACROSS MILENNIA

Jade’s toughness made it an ideal material for fashioning into Paleolithic and Neolithic hammers, axes, knives, projectile points, and other tools and weapons. This toughness late enabled stonecutters to carve jade into objects of unusual intricacy and detail without fracturing.

The Chinese reverence for jade surpasses that of all other cultures. When Chinese cutters began making detailed carvings about 3000 BCE, jade was already more than just a gemstone and carving medium. Symbolizing beauty, grace, purity, and the highest Confucian virtues, it soon became ingrained into Chinese culture. Even today, the Chinese view jade as a bridge between heaven and Earth, with its brightness representing heaven and its substance representing Earth.

For more than four millennia, Chinese cutters worked only with nephrite obtained from the Kunlun Mountains of far-western China. Then, in the late 1700s CE, a new jade became available. It came from the remote Hpakan region beyond China’s southwestern border and was superior to nephrite in color, translucency, workability, and overall appearance.

The Hpakan region of northernmost Myanmar rests atop a tectonic subduction zone where the Indian Plate is drawn beneath the Eurasian Plate. This crustal subduction generates sufficient pressure to alter peridotite, an ultramafic igneous rock, into serpentinite, a metamorphic rock consisting largely of serpentine-group minerals. Much later, regional uplifting fractured these serpentinite formations, enabling hydrothermal fluids to emplace dikes of nepheline (sodium potassium aluminum silicate) and jadeite.

Erosion slowly exposed these formations, and weathering reduced the serpentinite to sand and gravel. Secondary deposition then created formations of semi-consolidated conglomerate containing rounded pieces of the original jadeite dikes. These range from pea-sized bits to huge boulders; all have drab, yellowish-brown, oxidized surface “rinds” that conceal interiors of colorful, translucent jadeite.

Hpakan jadeite first reached China about 1300 CE. Chinese cutters admired its beauty and workability but were unable to locate its source. Only after gaining control of Hpakan in the 1780s did the Chinese find the source and begin systematic mining. In 1798, a trade route called the “Jade Road” opened between Hpakan and the interior of China. The subsequent steady supply of fine jadeite quickly inspired Chinese cutters to higher levels of creativity.

A clear mineralogical picture of jade began emerging in 1846, when French chemist Alexis Damour analyzed nephrite and identified it as an amphibole mineral. At that time, all jade was thought to be nephrite. But in 1860, during the Second Opium War, invading British and French forces sacked Beijing’s Summer Palace and shipped numerous jade carvings to Europe. In 1863, Damour analyzed this newly arrived jade and found that it differed chemically from nephrite. He identified it as a new pyroxene mineral that he named “jadeite.”

The Jade Road served as a trade route into China until World War II. But following the post-war Communist takeover of China, the Maoist regime discouraged material symbols and possessions such as jade. The Jade Road was then abandoned, and the jadeite trade shifted to Thailand and the then-British Dependent Territory of Hong Kong.

Meanwhile, Burma was undergoing its own political upheavals. Following decades as a British colony, it became an independent republic in 1948. Then, after a 1962 coup, its new military dictatorship banned foreigners, nationalized the economy, and entered into a period of strict isolationism.

The 30-mile-long Hpakan Jade Tract is located in northern Myanmar’s largely inaccessible Kachin State. Populated mainly by separatist ethnic groups, Kachin, through its Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), has long waged guerilla warfare against the central government, partially funding its activities by taxing Hpakan’s thousands of independent, artisanal jade miners.

If you enjoyed what you’ve read here we invite you to consider signing up for the FREE Rock & Gem weekly newsletter. Learn more>>>

In addition, we invite you to consider subscribing to Rock & Gem magazine. The cost for a one-year U.S. subscription (12 issues) is $29.95. Learn more >>>

Hide i

Hide i