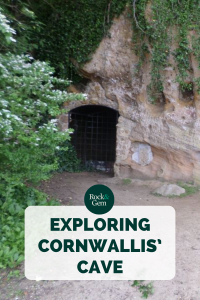

What Cornwallis’ Cave at Virginia’s Colonial National Historic Park is and isn’t might surprise you. It’s not a real cave and British General Charles Cornwallis probably never hid in it during the final weeks of the Revolutionary War. In fact, there are no natural caves in eastern Virginia. What, then, is Cornwallis’ Cave and why is it important?

An Odd Chapter in the Virginia History Books

It’s a feature along the base of the bluffs along the York River in Yorktown, Virginia, on the opposite bank of U.S. Route 17 from Gloucester Point. Though made of Pliocene epoch coquina, a type of sandstone composed of fossil shells (carbonates) and quartz, it is unrelated to actual karst features in the area. This feature is a cultural resource that was carved into the bluff.

Cornwallis’ Cave is approximately 40 feet in length. The National Park Service has placed a wrought iron gate at the entrance so most of the cave cannot be entered. It was one of the very early “tourist attractions” of 19th-century Virginia. If it had not been for that and for its use in the Civil War, it might have been leveled to make room for something else along this narrow shoreline.

Courtesy Deborah Painter

Karst Features

Ironically there are genuine karst features nearby in York County and in the city of Newport News. These are known as the Grafton Sinkhole Complex, an increasingly uncommon wetland complex now protected partially under U.S. Clean Water Act laws and some Commonwealth of Virginia regulations. These are small basins, often no more than 10 to 15 feet in width and three feet deep, that draw down in dry periods, exposing mud. There is usually a shallow organic layer overlying silt or clay loam. The sinkhole ponds are karst features that formed through the dissolution of carbonate shell marl deposits of the Miocene/Pliocene epochs, mostly the Bacons Castle Formation, which comprises part of the coquina of Cornwallis’ Cave.

The bluffs’ geologic units are the upper Pliocene Bacons Castle and Pleistocene Windsor Formation and the lower Pliocene epoch Yorktown Formation which is one of the predominant formations throughout the eastern Virginia area. The Yorktown Formation consists of shelly layers and sands and dates between four and 10 million years B.C.

Courtesy David Hawk

Fall Line

Ten to five million years ago the Atlantic Ocean reached the Fall Line that extends north to south in Virginia, closely following Interstate 95 south. The Fall Line is the demarcation between the Piedmont and the Coastal Plain in Virginia. It is where metamorphic and igneous rock bedrock meets the sandy outwash plain.

The Atlantic waters of the early Pliocene were a bit warmer than today. Scaphopods, corals, sponges, marine worms, pelecypods (Pecten clintonius), gastropods (Turritella alticostata), crustaceans and varieties of barnacles are common invertebrate fossils. Cornwallis’ Cave owes its structural integrity to being composed of cross-bedded coquina, a sandstone that has been cemented by salt spray from the York River. Ninety percent of the coquina is carbonate, and the rest is clay minerals, quartz and iron oxides.

Elsewhere along the bluffs are silty sand and shelly sand deposits distinguished by bluish-gray quartzose sand. The area of Cornwallis’ Cave sets itself apart from other portions of this bluff by the large-scale cross-stratification. The cross beds dip to the northwest at 24 degrees. Some trace fossils of crustacean burrows cut through the beds. This is important in understanding the inclined beds and how they were deposited.

Similar deposits have been discovered by geologists W.B. Rogers, J.R. Bowman and others in bore holes to the southwest of Cornwallis’ Cave, within the Colonial National Historical Park as well as in the Chuckatuck area of Suffolk about thirty miles south.

Courtesy National Park Service

Cross Beds at Cornwallis’ Cave

The question many have is why are the cross beds at Cornwallis’ Cave inclined. Were they not laid horizontally in the Atlantic Ocean? There are two hypotheses.

One is that the layers (beds) of shelly material accumulated horizontally and then were tilted by tectonic activity. Much of Colonial National Historic Park is located on a subsiding side of a rotating fault-bounded block.

Another idea is that the strata were deposited on an incline. On modern submarine shoals, one may see an incline of nearly 30 degrees. At Cornwallis’ Cave, the fossil burrows are trace fossils left by decapod crustaceans (Ophiomorpha) of several species. These burrows are nearly vertical.

Since the animals made the burrows when the sediments were laid, this is good evidence that the layers were deposited on a slope. The burrows would be tilted along with the layers if tectonic activity had inclined the sediment layers.

More protective measures have been needed for some time at Yorktown and nearby to protect the commercial and historic resources. Hurricane Isabel and Tropical Storm Isaias are recent storms that caused more erosion, mainly because of fallen trees at the bluff. Breakwaters were constructed years ago against the natural forces of longshore transport but have not stopped the relentless and inevitable pounding of the beachfront. The Virginia Institute of Marine Science is finalizing a plan to protect the estuarine York River shoreline.

Courtesy David Hawk

Cornwallis’ Cave: The Human History

It is unclear whether Cornwallis’ Cave was excavated before the American Revolution but it is believed that it was built to protect munitions from the elements. The tobacco and slave ship port dated as far back as the 1600s and featured a church, taverns, a medical shop and a few homes.

Some residents are reported to have sought shelter in Cornwallis’ Cave during the bombardments of the 1781 siege at Yorktown – the deciding battle of the American Revolution. Cut off from the ocean by French ships in the Chesapeake Bay, Lord Cornwallis fought the American and French in the Bay, returned to Yorktown and cut trees to build earthworks to surround the port.

Cornwallis crossed the York River with some men, and, being informed by men arriving in a small boat that British ships were en route, felt it was advantageous to remain at Yorktown. Dysentery then struck Yorktown. The British engaged the French and American forces for months. Overwhelmed by the Franco-American numbers both from the Bay and an October bombardment from the land side, Cornwallis found his troubles compounded by a savage storm, possibly a late-season hurricane. It temporarily trapped his men and vessels on the south side of the York River.

He probably used a bunker and not the Cave as a shelter because the men had to store munitions somewhere dry. General Cornwallis surrendered to American General George Washington and French General Rochambeau on October 19. There would still be skirmishes and engagements in the Colonies but this surrender marked the official end to the war. By 1848 “Cornwallis’ Cave” was the name given to the Cave and the owners gave tours.

Courtesy Deborah Painter

Yorktown

The small town played a vital role over an 87-year span in two wars, the American Revolution and the American Civil War. The shoreline area was used by the Confederate troops to store munitions. Five square depressions were dug in the outer wall of the Cave to insert timbers covered with planks. These were covered up in clay to deny any Union gunboats a view of the Cave and employed as a place to store gunpowder. Confederate General Magruder, and later General Johnston, built up the Confederate defenses.

The Library of Congress possesses several good photographs of this beachfront operation and of Cornwallis’ Cave. There are few historic sites in Virginia where balloon warfare was used, and this is one of them. Brigadier General Fitz-John Porter was in charge of siege operations for the Union army. Along with Professor Thaddeus Lowe, he made balloon observation flights in the Constitution and the Intrepid over the Confederate lines in April and May 1862, at the same elevation of shrapnel from ground artillery. Professor Lowe continued his flights unscathed.

The Confederates had their own hydrogen hot air balloon for gathering intelligence concerning the Union troops. The balloons were large targets but amazingly, none of them were ever struck. The Siege at Yorktown was long. But around midnight of May 3, 1862, the Confederate heavy guns had ceased firing and were spiked. The Union army continued the use of the Cave as a powder magazine.

After the war, Cornwallis’ Cave stopped being a tourist attraction and was used to store potatoes. During the Jamestown Exposition of 1907 which celebrated the 300th anniversary of the founding of Jamestown, Virginia landowners resumed tours for ten cents per person. In 1930 the National Park Service acquired a large portion of the land near Yorktown and established the Colonial National Historical Park.

Courtesy David Hawk

A Narrow Beach With Plenty To Do

Literally a few feet from “Riverwalk,” a pedestrian stretch of Water Street at the historic-themed beachfront, Cornwallis’ Cave is located at the face of a bluff managed by the National Park Service and is part of the Colonial National Historical Park.

Cornwallis’ Cave is approximately 1700 feet to the east of a small parking garage. A trolley bus sometimes makes runs from the historic Main Street landward of the bluff for added convenience. The Cave is the last stop along the run. Immediately west of Cornwallis’ Cave is a small historic home and outbuildings, identified as “An Archer House.”

No admission price is needed to see Cornwallis’ Cave. Regular “ghost tours” are run at night by a concession. In addition to the Archer House, one can enjoy other historic homes, a small hotel, a bookstore, a variety of restaurants, and a cluster of statues of the French and Continental Army generals who won our independence from Britain.

This story about Cornwallis’ Cave previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story Deborah Painter.