By Bob Jones

Gold is a native element that resists forming mineral compounds. Of the several gold compounds, only two are sometimes available to collectors: sylvanite and calaverite. Other less often available species include nagyagite — a lead, gold, antimony sulfide, and petzite — a telluride. Meanwhile, krennerite — a gold and silver telluride, is so rare I’ve only seen it in photographs.

On the other hand, silver readily forms mineral compounds with copper, arsenic, sulfur, and other elements. Silver compounds have regularly been found in quantity in many of the world’s great silver deposits. They often occur as excellent specimens available for sale if you can afford them. You certainly see silver minerals on display in many museums and private collections. Among the many silver species, there are uncommon silver species, including chlorargyrite, dyscrasite, and polybasite, which are seldom available for sale.

These few uncommon gold and silver minerals are certainly worth collecting when available. Some are also the subject of fascinating true stories related to their discovery. Did you know, for example, that one gold compound found in quantity in a rich gold-producing area of Australia was thought to be fool’s gold, so it was tossed on the dumps and later used as road fill in the developing town? You can guess what happened to those roads when someone figured out the “fool’s gold” dump rock was really gold. Fortunately for the state of Colorado, no one has dug up the “Million Dollar Highway” between Ouray and Silverton in the San Juan Mountains. It is so named because the road gravel was hauled in from nearby silver and gold mine dumps.

ROMANIA’S REIGN ON THE UNCOMMON

Historically, one of the better sources of uncommon gold species is Transylvania, now known as the Baia Sprie region of Romania. It has been producing gold species since before the Romans invaded the area. The region was the largest gold deposit in Europe. The deposits produced not only fine crystallized gold but also some of the finest rare gold and silver telluride species known, like nagyagite, petzite, calaverite, sylvanite, and others.

Since the gold deposits in Romania have been one of the great sources for gold and silver tellurides, it is no surprise the area is the type locality for the metal element tellurium. Named for “tellus” and “earth” in Latin by Martin Klaproth, tellurium is one of the few natural elements that will combine with gold and sometimes silver to form such rare mineral compounds as petzite, calaverite, nagyagite, and sylvanite.

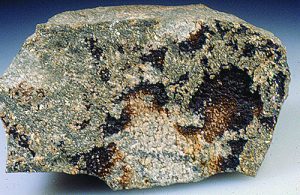

Nagyagite crystallizes in the monoclinic system, but crystals are rare. They tend to be small and dark grey tightly clustered on a matrix. Nagyagite was often encountered in Romania in relatively shallow, low-temperature hydrothermal deposits with other rare gold specimens. I’ve only handled one or two nagyagite specimens and was fortunate to own one for a time after I traded for it from a private collection years ago.

Calaverite is far more common than nagyagite but is still uncommon. The gold deposits of Kalgoorlie, Australia, produced quantities of calaverite, which went unidentified as a gold mineral because it looked so much like fool’s gold, so it was tossed aside. Needing road fill, Kalgoorlie used the dump rock with the lustrous silvery to pale yellow metallic species until it was shown to be gold telluride. The local prospectors immediately began digging up the roads to recover the yellow metal. I’ve been to Kalgoorlie since, and the streets are fine now!

CRIPPLE CREEK’S CLAIMS TO FAME

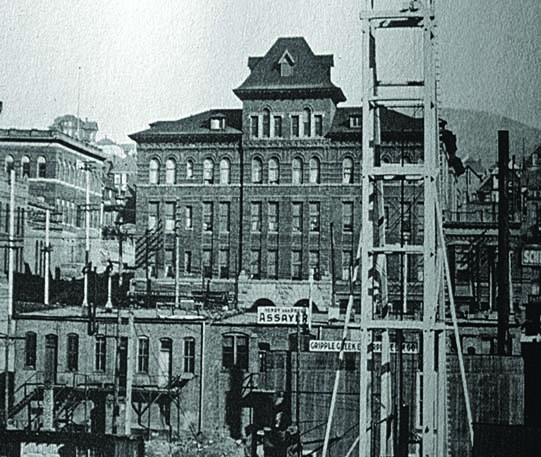

Here in this country, calaverite is normally an uncommon gold species but was very common at Cripple Creek, Colorado, the richest gold discovery made in that mountainous state. Again, this gold telluride was not recognized early on, and many who had an opportunity to strike it rich in the Cripple Creek area passed it by until the 1890s when Cripple Creek became the last big gold strike in Colorado.

Gold and silver discoveries were being made all over Colorado in the second half of the 1800s, yet Cripple Creek was really late to the rush because the gold went unrecognized. It was known earlier by a local cowboy, Bob Womack, who struggled for years convincing folks he had found gold on Pike’s Peak’s western slopes. Womack was sure he had found gold, but no one would listen because the samples he had were calaverite and sylvanite and didn’t look like gold. He even displayed specimens in Colorado Springs’ store windows, trying to find investors, but no luck. Finally, the ore was checked and proved to be rich in gold species calaverite and sylvanite, and the rush was on. Of course, poor Bob ended up being aced out of his finds.

Did you also know Cripple Creek was named for a cow that fell in a creek and broke one of its legs?

Once the word “gold” was out, the place boomed, fortunes were made, and amazing true stories about Cripple Creek abound. One of my favorite Cripple Creek tales is about William Stratton. In 1891, he staked claims and began mining his Independence mine. He labored for months but was not very successful. He finally had had enough and decided to lease his holdings to another miner, which he did. On his last day underground in the Independence mine, he broke into a very rich gold vein.

Now, what to do? He knew the lessee would take over the mine the next day, so he buried his discovery and held his breath for a month. The lessee worked the mine for a month without finding Stratton’s hidden gold vein. On the last night of the lease, Stratton was having dinner with the lessee. As they sat in front of a roaring fire enjoying their cigars, the leaseholder admitted failure, pulled out the lease, and handed it to Stratton. Stratton was shaking so much he simply suggested the fellow toss the lease in the fire, which he did, not realizing he had thrown away a fortune! Stratton worked his rich vein in the Independence mine and became one of the first Cripple Creek millionaires with one of the richest mines.

Stratton’s near-miss is just one of the true stories of the area. The accidental discovery of a cave lined with gold is even harder to believe but is true. It happened at the Cresson mine in Victor, the town next to Cripple Creek. How would you like to be a miner who broke in-to a big cave lined with sparkling gold crystals? It happened more than once in Cripple Creek. In 1953, a small cave was encountered lined with calaverite and sylvanite crystals. The Cresson mine has since proven to be the richest property in the Cripple Creek/Victor area. It was operated underground and later as an open-pit until recent years.

But the earlier 1914 find in the Cresson is really beyond belief. In the early 20th century, during the drifting of a tunnel, Rick Roelof’s crew broke into a room-sized cave measuring 36 feet by 14 feet by 23 feet. The cave walls were covered with crystallized gold. Reports don’t suggest if it was native gold, calaverite, or sylvanite, but it was probably all three minerals. The owners immediately installed a steel door, and the cave walls were “mined” in secrecy. I shudder to think of the myriad crystallized specimens miners scraped off the walls, bagging them and hauling them to the surface for smelting! It took a month to mine all the cave’s gold, and the total value is something over $50,000 at $20 an ounce! Today, that’s millions of dollars.

One of the interesting things about Cripple Creek gold, where so much was in the form of calaverite and sylvanite, is what we call blister gold. More than 50 years ago, you could go into Cripple Creek shops and buy a specimen of blister gold, a small ore specimen that had been heated to drive off the tellurium leaving behind small bubbles of yellow gold on the rock surface. Today, if you are looking for either of these uncommon gold compounds from Cripple Creek, check on the internet, and check with every local dealer in Denver.

Silver species are far more available these days than gold compounds. Even something as uncommon as dyscrasite shows up now and then. Some years ago, dyscrasite was almost never available, and then a large batch of this silver antimonide came on the market from Pribram, Czech Republic. The specimens are lovely clusters of elongate cylindrical shafts spraying off in all directions. They are black with a steely luster, and many of the crystals were twinned. Occasionally, a specimen of this material is available for sale even today.

The original dyscrasite was found in Germany and was given a name meaning “bad alloy” because it messed up the smelting process. More recently, it has been found in the silver mines of Morocco, and a few specimens from that locality appear on the market at times.

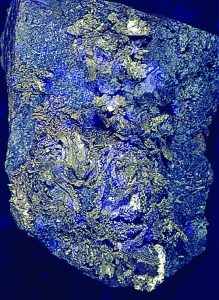

Polybasite, a very complex silver species, is not rare. Composed of lead, copper, arsenic and antimony, it is a lustrous black with slightly visible red reflections on its edges that helped identify it. The problem is it can easily be confused with other silver sulfides, so it is often mislabeled. There are enough specimens available on the internet and occasionally at a show, so a collector who can afford polybasite should have little trouble finding a specimen. Be sure to check for that red reflection on a mislabeled specimen.

The hard-to-get silver specimen is chlorargyrite, silver chloride. It forms close to the surface of silver deposits, where weathering has broken down the exposed silver compounds. The mineral is very soft, hardness one to two, and seldom forms crystals. It is most often found in waxy masses during the initial opening of a deposit, proving a rich ore source initially. It is often referred to as horn silver, and it is a light-sensitive mineral, so it readily fades from a light yellow to dark brown to even purple. It can form crystals, small and usually brownish in monoclinic form, but these are really rare. As a silver ore, it was very important in the very early days of mining at Tombstone, Arizona, and other deposits, but collector specimens are quite difficult to obtain and are seldom very attractive.

Calaverite was first found in the gold veins of the Stanislaus gold mine, Calaveras County, California, in 1881, hence the mineral name. I suspect calaverite had been encountered before that in California, but it could very well have been ignored for years.

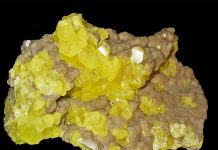

Calaverite is gold telluride. It has a high metallic luster but is most often seen as a gray-white lustrous crystal, often showing minor striations, and does not resemble the pure metal. It can occur with a light yellow color but was often bypassed, as earlier mentioned, in Kalgoorlie, Australia. Chemically, calaverite is closely related to sylvanite, gold, silver telluride, and if you find one, you should find the other. Good luck!

For the serious collector, these uncommon to rare gold and silver species are not prize winners, but as very hard-to-get species, they are well worth the hunt when found.

Author: Bob Jones

Holds the Carnegie Mineralogical Award, is a member of the Rockhound Hall of Fame, and has been writing for Rock & Gem since its inception. He lectures about minerals, and has written several books and video scripts.

Holds the Carnegie Mineralogical Award, is a member of the Rockhound Hall of Fame, and has been writing for Rock & Gem since its inception. He lectures about minerals, and has written several books and video scripts.

If you enjoyed what you’ve read here we invite you to consider signing up for the FREE Rock & Gem weekly newsletter. Learn more>>>

In addition, we invite you to consider subscribing to Rock & Gem magazine. The cost for a one-year U.S. subscription (12 issues) is $29.95. Learn more >>>

Hide i

Hide i