By Helen Serras-Herman

The Greek island of Nisyros lies in the middle of the Aegean Sea. It is part of the Dodecanese Island group and sits between the more famous Kos and Rhodes islands. Nisyros is a 9-km wide, mountainous and rocky island, formed by volcanic lava. At the center of the island, is a two-mile-wide caldera with active fumaroles, hot gases bubbling up through the mud, and hot springs.

Nisyros is one of the more active but less known volcanoes in Greece. Together with the Kos caldera volcanoes, Nisyros is part of the Hellenic arc, a curved line that includes the active volcanoes of Methana, Milos, and Santorini (http://volcano.oregonstate.edu ). My husband and I visited the island as a day trip via a small ferry boat that departed from the island of Kos, where we were staying. The journey takes about 50 minutes—with the boat docking at Mandraki, the main town, and harbor of the island. The harbor area is picturesque, with narrow streets and white-washed two-story houses with vibrantly painted blue wooden balconies and stunning, brightly colored hanging bougainvilleas.

Mythology With Ties to Volcanic Activity

According to Greek mythology, the island formed when Poseidon cut off part of Kos and threw it onto Polybotes, one of the Greek Giants, to stop him from escaping. That may be the mythological tale, but it reflects the true geological occurrence. The first sub-marine eruptions on Nisyros took place 150,000 thousand years ago. Twenty-four thousand years ago, a violent eruption left a huge caldera in the center of the island. Two major craters now occupy the caldera. Five solidified lava domes and ash cones were produced after the formation, by more recent activity. The initial eruption was accompanied by an outpouring of pumice, which formed a 328-feet thick blanket on the island’s upper slopes. The volcano is classified as dormant active, as its last eruption was approximately 15,000 years ago. In addition to the volcanic activity, there have been hydrothermal explosions, which are releases of superheated geothermal fluid, on the caldera floor.

Ten well-preserved hydrothermal craters are the result of 5,000 years of recent activity. Polyvotis is the largest crater of the volcano, measuring 260 meters (853 feet) in diameter and 30 meters (98.4 feet) deep. Additionally, five younger craters exist in the same area, the largest being the Stefanos crater. This second crater is ellipsoid in shape, with a diameter of about 300 meters (1,000 feet) and a depth of 25 meters (80 feet), and two dacite domes form the west wall of the depression. The Stefanos crater is still active, with several hot springs and boiling mud pools and gas vents, giving it the appearance of a moonscape. It is one of the largest and best-preserved hydrothermal craters in the world.

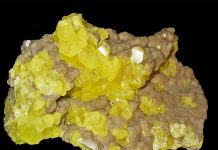

While on-site, we stood at the edge of the caldera and took in the imposing view. The smell of rotten eggs – the stench of sulfur- is powerful as you approach the opening. Interestingly, the formation of sulfur crystals gives the impression of a golden field. The golden hue is clearly visible as visitors descend the crater following narrow and steep paths winding down to the caldera floor, where the surface is hot enough to melt rubber-soled shoes. Although there are moments of calm, while one stands on the floor, vents that expel steam at 212 degrees Fahrenheit, can suddenly become active. The welcome sign warns visitors about gasses and fluids being scorching and corrosive and not coming in contact with them.

The most recent hydrothermal explosions at the Stefanos crater took place in about 2000 BC. In the smaller crater, the Micros Polyvotis, eruptions accompanied by earthquakes took place as recently as the late 19th century.

Seismology, Springs, and Sulfur

The island, which attracts thousands of visitors each year, is continuously monitored for seismic activity, and thermal and chemical changes. If the volcano becomes active, the gaseous and liquid phases contained in the magma will reach the surface earlier, often causing dramatic changes to the chemical composition of hot gases (fumaroles) and springs.

Among the earliest mentions of the abundance of sulfur from this region appear in

Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. The Phenicians were the first to mine sulfur on Nisyros, followed by the Greeks, and even as recently as the mid-20th century, it was the focus of mining efforts. Sulfur is a significant raw material in the chemical industry, used primarily for the production of sulfuric acid, fertilizers, paints, explosives, fireworks, and rubber. It is also prevalent in the metallurgy and pharmaceutical industries. While there are no active sulfur mines in Greece any longer, it is obtained through gas and natural gas desulfurization.

During our travels throughout the region, while we were on the way to Nisyros from the island of Kos, we saw the rhyolitic obsidian lava domes and pumice deposits on the nearby islet of Yali, or Gyali (glass). Perlite and pumice are natural materials mined on the islet. Perlite is an amorphous volcanic glass, with relatively high-water content. Today it is used as an industrial mineral. In antiquity, obsidian was also extracted by the inhabitants of Nisyros.

Another fascinating place to visit in the area is the Volcanological Museum of Nisyros, which is located in a small building in Nikia — the closest village to the volcano. The museum displays local rocks, photos, and extensive information about the geology of the island, the volcano of Nisyros, and other active volcanoes in the world. The Archaeological Museum of Nisyros and the Folklore Museum, both in Mandraki, explore the history of the island from prehistoric times to modern-day.

If you are seeking a once-in-a-lifetime volcanic adventure, a visit to the beautiful island of Nisyros and its active volcano will definitely satisfy your quest for exploration. The beautiful sandy beaches, brilliant sun, warm hospitality by locals, and enormous history will only augment that sentiment.