Flint from Flint Ridge, Ohio, is prized by flintknappers, lapidaries, jewelry makers, and mineral collectors. Along with a fascinating history and geology, it’s no wonder that Flint Ridge flint with its rainbow of colors and ability to take a superb polish is also Ohio’s official state gemstone.

Rolling Countryside With Unique Geology

Flint Ridge, located in southeast Ohio about 40 miles east of Columbus, the state capital, is an unimposing, low escarpment in the gently rolling farm country just north of Interstate 70. While the topography of Flint Ridge may be unremarkable, that’s not the case with its cultural significance. As a source of high-quality flint, Flint Ridge began attracting Native Americans some 12,000 years ago and is still drawing people today.

Flint Ridge is the site of the Flint Ridge State Memorial and the Flint Ridge Ancient Quarries and Nature Preserve. Attractions include a museum with informative flint-related exhibits, trails leading to hundreds of prehistoric flint quarries, two annual flint-knapping events, and a nearby fee-collecting site, where rockhounds can collect their own colorful specimens of Flint Ridge flint.

About Flint

Flint is a type of chalcedony, the microcrystalline variety of quartz. Chalcedony’s other subvarieties are agate, jasper and chert. While agate and jasper are almost pure chalcedony, chert and flint are impure forms. Because of their variable chemical compositions, they are classified as rocks.

The terms “flint” and “chert” overlap and are sometimes used interchangeably. Both occur as nodules or layers within formations of limestone, dolomite or chalk. Flint is generally considered a finer-grained, more homogenous, and somewhat harder type of chert. It also exhibits a better-defined conchoidal fracture that lends itself to flaking. Knappers take advantage of this property to shape tools from the flint.

Tough, Durable, and Colorful

As a high-silica, chemical-sedimentary rock, flint is dense, tough, durable, fine-grained, and quite hard (Mohs 7). It resists erosion and can occur in a wide spectrum of colors. Along with chalcedony, flint also contains small amounts of water, calcite, carbon, various iron and manganese oxides and hydroxides, and the opal-like mineral mogánite (hydrous silicon dioxide, SiO2·3H2O).

As a product of the solidification of silica-rich solutions or the alteration of silica-rich materials, flint forms through one or a combination of three processes: compaction and crystallization of microscopic, siliceous skeletal structures; precipitation of silica from seawater; or the replacement of calcite in limestone by silica in groundwater.

Conchoidal Fracture

Flint’s most notable property is its conchoidal fracture, which is diagnostic in all types of quartz. Conchoidal fractures appear as smoothly curving, concave breaks that are generally similar in shape to the inner surfaces of bivalve mollusk shells. The word “conchoidal” itself stems from the Greek konchoeids, meaning “like a mussel”.

When flint is struck by an edged or pointed object, fracturing and an accompanying shockwave of mechanical energy begin at the point of impact. Within microseconds, this fracturing and energy progress through the flint at an angle slightly declined from the surface. Fracturing absorbs part of the shockwave energy which, as it decreases, exerts its greatest pressure in the direction of least resistance. This “steers” the developing fracture back toward the surface, displacing a thin flake of flint and leaving behind a conchoidal depression.

Ancient Knapping in Action

Conchoidal fracturing is the mechanical basis of flaking or knapping, a Paleolithic skill and an art that survives among flint knappers today. Because systematic flaking can create weapons and tools with points and sharp edges, flint has played a huge role in technological advancement throughout the human story. Because of its abundance, hardness, and ability to be flaked into utilitarian forms, flint was the dominant technological material throughout the Paleolithic and Neolithic stone ages.

And flint retained its technological importance long afterward. During the early Iron Age, most cultures with access to iron developed iron-flint “fire starter” devices. These employed shaped pieces of flint to shatter iron into microscopic particles that oxidized instantly in a shower of sparks.

By 1570, iron-flint sparking mechanisms were being used in flintlock rifles, which employed shaped flints attached to spring-loaded, metal arms. Depressing the trigger moved the arm forward, striking the flint against an iron plate to create sparks that ignited the gunpowder charge.

Fashioning flint into precisely shaped “gunflints” was an important industry in Europe during the 1700s. Manufactured and exported worldwide by the millions, gunflints remained a major trading commodity until they became obsolete after the development of percussion firing caps in the 1830s.

Uncommon Characteristics

Flint sources exist worldwide. Europe’s biggest deposits are hosted in the massive limestone formations of southern England and France’s Paris Valley. In the United States, notable sources are the Flint Hills in eastern Kansas, Alibates Flint Quarries National Monument and other nearby sites in the Texas panhandle, and localities in southeastern Ohio.

Ohio’s many flint deposits occur in limestone formations that are between 440 million and 300 million years old. These originated during the mid-Paleozoic Era as marine sediments on the floors of warm, shallow seas that covered what is now Ohio.

Notable Occurrence

Ohio’s most notable flint occurrence is Flint Ridge, where flint nodules and layers are hosted by the Vanport Formation of the Allegheny Group. The Vanport Formation consists of early Pennsylvanian Period lacustrine and marine limestones that are roughly 320 million years old. The flint nodules within the Vanport Formation formed when silica replaced the calcium carbonate in limestone; the layers originated through the alteration and solidification of sea-bottom beds of siliceous ooze derived from the silica-rich support structures of sponges and other marine invertebrates.

At Flint Ridge, flint occurs as long, weathered, discontinuous beds from 1 foot to 12 feet thick, with an average thickness of 4 feet. Originally buried under sea-bottom sediments, these beds were eventually exposed by glacial scouring at the end of the Pleistocene Epoch ice ages, some 15,000 years ago. Flint Ridge itself is a product of flint’s hardness and durability: While glaciation scoured away the limestone host rock, the flint beds resisted erosion to become the backbone of a low ridge.

Flint Ridge is an eight-mile-long escarpment with intermittent flint exposures that cover a ridgetop area of nearly six square miles. Attracted by the abundance, accessibility, and unusual quality of this flint, archaic hunter-gatherer groups began systematic quarrying at Flint Ridge about 12,000 years ago, making it one of North America’s oldest known mining sites.

Source of Protection

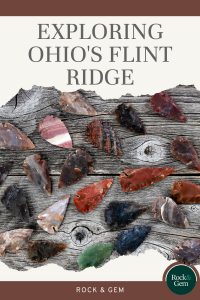

These cultures flaked flint into arrowheads, spear points, scrapers, awls, and small knives called “bladelets.” Flint Ridge flint was utilized most extensively by a network of Midwestern tribes known collectively as the Hopewell Culture, which thrived during the Middle Woodland archaeological period from 100 BCE to 500 CE.

The Hopewell Culture was characterized by advanced farming methods and trading patterns, and Flint Ridge flint was one of its most important trading commodities. Hopewell groups traded flint for native copper from Michigan, sheets of the mica-group mineral muscovite from North Carolina, shells from the Gulf of Mexico, and obsidian from the Rocky Mountains. The broad geographic extent of this trade is apparent in the recoveries of distinctive Flint Ridge flint from archaeological sites as distant as the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, and points west of the Mississippi River.

Native Americans continued quarrying Flint Ridge flint until the arrival of European settlers disrupted their societies. By the late 1700s, these settlers had also begun utilizing Flint Ridge flint, flaking the higher grades into fire starters and gunflints. They fashioned the lower grades into “whetstone” wheels for sharpening knives, and into large, flat “buhrstones”, several feet in diameter, for grinding grain. Commercial quarrying ended at Flint Ridge around 1840, shortly after chemical matches and percussion-cap firearms made iron-flint fire starters and flintlocks obsolete.

Charles Smith, the first archaeologist to study Flint Ridge, published his findings in the 1884 Smithsonian Institution annual report and in his 1902 book Archaeological History of Ohio. Then in 1920, William C. Mills, former Curator of Archaeology for the Ohio Historical Society, excavated numerous quarry pits. His recoveries confirmed that the Hopewell Culture had conducted the most extensive quarrying, and had flaked the flint into two basic forms: leaf-shaped “bifaces”, worked on both the front and back; and small, cone-shaped cores that were preforms for bladelets.

Ohio’s State Gemstone

The Ohio Historical Society recognized the cultural significance of Flint Ridge in 1933 by establishing the Flint Ridge State Memorial at a site where archaeologists had found the greatest concentration of ancient quarries.

In 1965, long after cut-and-polished Flint Ridge flint had gained popularity in jewelry, the Ohio General Assembly adopted it as the official state gemstone, citing its beauty and importance to both Native American cultures and early Anglo settlers. Three years later, the state built a museum at the Flint Ridge State Memorial.

Different Flint Varieties

In 1987, Ohio State University Professor of Anthropology Richard Yerkes performed field studies at Flint Ridge that refined existing ideas of exactly how the Hopewell Culture quarried flint and fashioned tools.

By then, geologists had also refined their ideas about the origin of Flint Ridge flint. Comparative studies with flint from other sources indicated that it had formed in shallow, brackish, inshore waters at the mouth of a delta. Such conditions produce flint that is somewhat less homogeneous than that originating in deep-water environments.

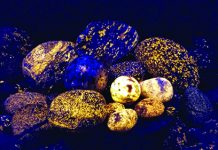

Flint Ridge flint varies greatly in its morphology and mineralogy, and occurs in four general types. Two of them are opaque, massive, white flint and porous, light-brown flint, which are impure and fracture unevenly; both are unsuitable for flaking and were used to manufacture buhrstones. The other two types, which have higher levels of purity, include translucent, bluish-gray flint and colorful, banded “ribbon” flint.

Both have excellent flaking properties and serve as gemstones today.

Quartz Presence

In some specimens, fractures are filled with macrocrystals of colorless quartz that formed through the secondary circulation of silica-rich solutions. Other specimens exhibit fossilized structures of sponges and other marine-invertebrate organisms.

Today, the Flint Ridge State Memorial and the Flint Ridge Ancient Quarries and Nature Preserve are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Within the preserve’s 533 acres are two miles of hiking trails that pass hundreds of ancient quarries and workshop sites. These quarries, ranging in size from 12 to 80 feet in diameter and from 3 to 20 feet in depth, are now visible only as gradual surface depressions.

The Flint Ridge State Memorial museum is built directly over an ancient quarry with exposed walls of in situ flint. Exhibits interpret the regional geology, explain how Native Americans quarried the flint and worked it into tools and weapons, and describe the prehistoric and historic uses of flint. The museum also distributes “Flint: Ohio’s Official Gemstone” (Ohio Department of Natural Resources Educational Leaflet No. 6, 2016), a well-written and nicely illustrated account of Ohio flint prepared by local geologist Garry L. Getz.

The museum’s gift shop offers a wide selection of Flint Ridge flint jewelry, spear points and arrowheads created by local flint knappers, and tumbled pieces of flint in many colors and color combinations, ranging from white, black, and pale hues of blue and grayish-blue to saturated blues, greens, reds, browns and yellows. Many multicolor specimens have intricate swirled, streaked and banded patterns.

The black color in Flint Ridge flint is caused by inclusions of elemental carbon from organic sources; the whites represent sections of essentially pure chalcedony. The “rainbow” hues are due mainly to traces of oxides and hydroxides of iron and manganese.

Flint Jewelry

Because of its extremely fine grain, this flint takes a superb polish. Its various colors make it look like a top-quality, multicolor jasper. Flint Ridge flint jewelry is sold regionally under such names as “Ohio Flint”, “Vanport flint”, “Hopewell flint”, and “Flint Ridge flint”.

Flint Ridge flint also reacts well to heat treatment. Archaeologists believe that Native Americans learned accidentally that flint was more workable after it had been exposed to fire. Today, local flint knappers routinely heat-treat Flint Ridge flint to enhance its workability, although they disagree on exactly how heat alters the stone.

Some believe that microcrystals within the flint fuse and make the material more homogeneous and easier to flake; others contend that heat creates microscopic cracks that slightly weaken the flint’s structure, thus improving its workability.

Heat treating also enhances colors and color contrast, mostly by increasing the intensity of the reds and blues, an effect that is likely due to further oxidation of the chromophoric iron and manganese compounds within the flint. Heating also results in smoother, waxier surfaces on the conchoidal fractures of newly flaked flint.

Knap-Ins

The Flint Ridge State Memorial is the site of two annual “Knap-Ins” hosted by the Flint Ridge Lithic Society and the LickingValley Heritage Society. These three-day events include family activities and showcase the region’s best flint knappers, who demonstrate their skills by fashioning arrowheads, spear points, and knives from the local flint. Held during the long Memorial Day and Labor Day weekends, these Knap-Ins are hands-on opportunities to learn about flint knapping from experts.

Flint collecting is not permitted at the Flint Ridge State Memorial or the Flint Ridge Ancient Quarries and Nature Preserve, but collectors are always welcome at Nethers Farm, four miles east on Flint Ridge Road. Popular for decades among collectors, Nethers Farm provides easy access to exposures of colorful, high-quality flint. Collectors can gather loose pieces or use hammers and chisels to remove pieces from the many exposures.

The collecting fee at Nethers Farm is $5 and 50 cents per pound of specimens removed. Payment is made on the honor system; if no one is at the farm, collectors weigh their specimens on a scale on the farmhouse porch and leave their fees in an envelope.

Despite its great prehistoric and historic importance, flint has no modern technological uses. The “flint” in modern cigarette lighters, welding strikers, sparkers, and survival-kit fire starters is not natural flint, but ferrocerium, an alloy of iron and the rare-earth metal cerium. When scraped against any hard, edged material, ferrocerium creates a shower of sparks that are much hotter than those produced by flint and iron. Over 1,000 tons of ferrocerium are manufactured worldwide each year for use in various sparking devices.

Where To Go

The Flint Ridge State Memorial and the Flint Ridge Ancient Quarries and Nature Preserve are located at 15300 Flint Ridge Road in Glenford, Ohio, three miles north of I-70 Exits 141 and 142. The museum is open from May 1 to mid-October, and by appointment only during the winter. The hiking trails, which pass hundreds of ancient quarries, are open year-round from dawn to dusk. For information on the Flint Ridge State Memorial, the Flint Ridge Ancient Quarries and Nature Preserve, and the spring and fall Flint Ridge Knap-Ins, visit www.flintridgeohio.org. The Nethers Farm fee-collecting site is located at 3890 Flint Ridge Road.

This story about Flint Ridge in Ohio previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Steve Voynick.