Fluorescent rocks are popular with collectors. Here’s a look at the history of mines in the Franklin-Sterling Hill area of New Jersey with more fluorescent minerals than anywhere in the world.

In the 19th century, immigrants from Russia, Ireland, Hungary and Poland flocked to Franklin, New Jersey to coax zinc, iron and manganese out of the earth in the mine there. These days, the mine is long played out, but the place where it was located is still a draw for a range of visitors from the curious to serious geologists.

“I have all types of people visiting the shop, from beginners to novice to high-end collectors and dealers and people who are just curious about Franklin minerals,” says Ted Bayles, proprietor of Franklin Mineral Rock and History, LLC on Main Street in Franklin, New Jersey.

“People who come in the store are split half between locals and half those from around the country, and I have had people from Germany and China, one gentleman from Greenland plus a lot of geologists from museums in New York and around the country.”

So what’s the draw to fluorescent rocks? History, mainly, says Bayles and a desire to study what’s been buried in the earth.

From the Beginning

The mining industry in Sussex County New Jersey began as long ago as the 1630s when the Sterling Hill Mine in Ogdensburg was established by a land grant from King George III to William Lord Sterling Alexander because it was thought to contain an extensive copper deposit. Its twin site, The Franklin Mine site was discovered in 1750 as part of the Franklin-Sterling Hill Mining District.

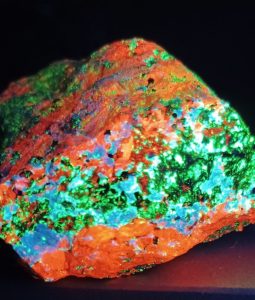

By 1765, Sterling sold the mine to Robert Ogden. Thereafter it was found to contain 357 types of minerals including Franklinite, found nowhere else, as well as zinc silicate and zinc oxide; none of which was commercially mined anywhere else in the world. Esperite, clinohedrite, hardystonite as well as johnbaumite and mcgovernite were also found there.

As a result, by 1897, the influx of immigrants and domestic miners working the Franklin mine and the Sterling Hill mine, a little more than two miles away in Ogdensburg, ballooned Franklin’s population from just 500 to more than 3,000 in 1913.

While the operations were active, the zinc extracted from mine shafts was used in high-grade exterior and interior paint, rubber tires, shoes and hoses. At the same time, the ceramics industry used zinc oxide to manufacture enamelware, glass and general tableware, and finally, the cosmetic industry used zinc oxide in face powder, creams and sunscreen.

Mining operations at the Franklin mine ended in 1954 when the last of the ore it contained was brought to the surface. Operations at the Sterling Hill mine continued until 1986 when zinc prices tanked.

A Collector Hotspot

A Collector Hotspot

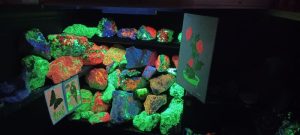

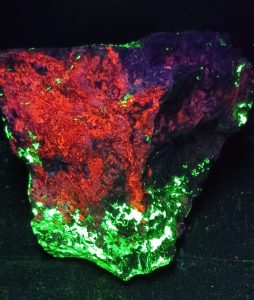

Materials derived from the mines also caught the attention of collectors who were attracted to the fluorescent rocks for their beauty, rarity and because under ultraviolet light many of them emitted a colorful, fluorescent glow.

“Some of the daylight colors of the minerals are very beautiful, too,” Bayles says. For a while, minors sold the material to collectors from their own private collections kept in their homes. Among them was Raven Youngman, a carpenter turned mineral sculptor.

“He was always looking for interesting stones to carve and he was into UV stones for a while,” recalls his son Eric Youngman who along with his wife Susan operates the Soul2Shine rock and mineral emporium in Bellingham, Washington. “For a while, Franklinite was pretty popular, and we sold quite a bit of it to collectors.”

Preserving the Franklin Mine

In 1959, a group of collectors from the area formed the Franklin-Ogdensburg Mineralogical Society (FOMS) which became instrumental in establishing the Franklin Mineral Museum. The local Kiwanis Club stepped in and adopted the museum project and in 1965 the Franklin Mineral Museum opened to the public.

Scientific Research

Scientific Research

These days, in addition to being a destination for touring school children and visiting amateur and professional geologists, the Museum supports the research projects of scientists at universities throughout the United States, says geologist and Franklin Mineral Museum Curator Earl Verbeek, Ph.D. “Researchers are mostly from the U.S., and mostly from universities. Some are also mineral collectors with an interest in the science.”

The museum’s support includes access to the Franklin Mineral Museum’s proprietary collection of fluorescent rocks no matter where the researcher is located. “Specimens are commonly sent by mail,” Verbeek says. “Generally, only small fragments of specimens are needed for analysis, but on occasion, we will loan an entire specimen for study.”

Those conducting research at the Franklin site may also use both petrographic microscopes, used to view mineral characteristics, and stereo zoom microscopes, which allow a three-dimensional view, for mineralogical study.

The Museum occasionally funds research with small $500 to $2,000 grants.

“For years this museum coordinated funding and logistical support for the mineralogical research of Pete J. Dunn, a former mineralogist at the Smithsonian Institution and author of the five-volume series on the minerals of Franklin and Sterling Hill, published in 1995,” Verbeek says. “These volumes serve as the ‘bible’ of Franklin-Sterling Hill mineralogy and have an international following.”

More recently the Museum coordinated funding and logistical support for a three-volume photographic record of the minerals of Franklin and Sterling Hill. Published in 2022, the book series identified dozens of minerals and inspired additional research.

What is Franklinite?Geologically speaking, Franklinite put New Jersey on the map. It was discovered in 1819 and is found nowhere else but in Franklin (its namesake) and Ogdensburg, New Jersey. This oxide mineral is an ore of zinc and manganese. Franklinite is black in color and is not fluorescent but is often found with fluorescent rocks such as calcite and willemite. Franklinite has its own set of metaphysical attributes too, claims Eric Youngman of Soul2Shine. Associated with the Gemini astrological sign and the base energy or chakra of the human physical body, Franklinite is said to help those to possess it to grow hair, treat male reproductive disorders and promote ocular health, he says. |

Preserving Sterling Hill

Meanwhile, in 1987, Dick and Bob Hauck bought the Sterling Hill site at a tax sale in order to establish the Sterling Hill Mining Museum.

The Museum opened to the public in 1990 and currently conducts tours of the restored mining site and permits rockhounds to peruse the mine dump located on site. In 1991, the site was listed on the New Jersey and National Registers of Historic Places.

Franklinite Fame?

Franklinite Fame?

Despite the role that the Franklin-Sterling Hill minerals have played in the region’s reputation and subsequent economy, attempts to designate Franklinite as the official mineral of the State of New Jersey have languished in the state’s legislature.

According to the New Jersey Legislature press office, the most current legislation, A3393, is under review by the State Assembly’s Environmental Committee. A twin bill S1727 was introduced into the State Senate. Both bills are pending.

Even so, the measure’s legislative success matters little to the collectors who continue to seek Franklinite and fluorescent rocks.

“Franklinite or Franklin minerals, in general, are very sought after and highly collected by a very small group of collectors and are worth only what people will spend on them,” says Ted Bayles.

“For myself and all the collectors that come in my shop, a rockologist (is) a person who has a passion for digging up Rare Minerals – it’s like finding history in the ground,” he explains. “Plus, it’s addictive and a massive adrenaline rush when you find something rare.”

This story about fluorescent rocks previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Pat Raia.