Fluorite, an often beautiful mineral, is found in collections of all levels. Many collectors have started with fluorite, finding it more accessible and affordable than many minerals. On the other hand, many a collector, as they and their collection have grown and matured, have made an equal effort to add fluorites. For some of us, it’s hard to stop (picture me looking innocent here). So, let’s begin our exploration into this most wonderful mineral.

Oh, and did I mention it can be really stunningly cool, too?

The Basics

To create context and really help the interest factor, here are some fluorite basics that won’t make you groan with boredom.

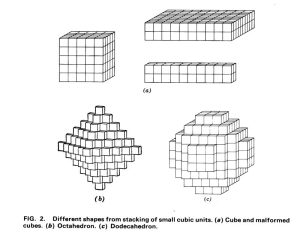

The composition of fluorite is CaF2, and it grows within the isometric (cubic) crystal system—basically, it tends to grow in cubes.

However, tinker with the temperature as it grows and the cubes (made up of molecular unit cells that compose the fluorite), can begin to shift as they grow and repeat.

You can find fluorite crystals that look like cubes, octahedrons, dodecahedrons and many crystals combining these shapes. Fascinating and attractive all at the same time, the variations can number in the hundreds (better get some more display cabinets).

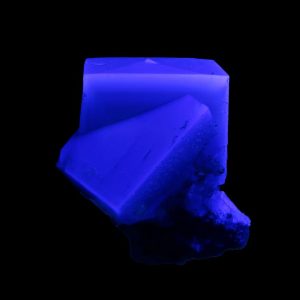

Also, fluorite has perfect cleavage. Looking at the a, b and c axes, fluorite will cleave along the (1,1,1) plane. In the isometric system, that means it will cleave in an octahedron.

If you really get good at it, it’s waste not, want not. Even these can be gorgeous and worth collecting. What a deal!

A Gangue Mineral

Fluorite is often referred to as a ‘gangue’ mineral, which by definition implies it is a waste accessory to ores during mining. Often it grows in hydrothermal veins, but it can grow in many other underground environments, even pegmatites. And in these two sentences lie the secrets to our success. Under the circumstances of being just an ‘accessory’ mineral, fluorite tends to be more common and for that reason, as I said before, more affordable. Also, when you see pictures of fluorites in place or on specimens, more often than not you are actually seeing the fluorite, hopefully well-crystallized. But why?

If you think about the fluids in a hydrothermal vein cooling down with the different minerals growing out of the solution, and the fact that you can actually see the fluorite crystals, they must be growing late. Yes! Fluorite is a low-temperature mineral that grows between 60 to 160°C. Lucky for us!

As an example, I’ve been fortunate enough to collect underground at the Blanchard Mine in New Mexico (Just over the mountain and a full day’s walk to the Trinity Site, by the way. Very neat, but please don’t do that). Going into the Sunshine #1 adit (underground passageway), you can walk back into the tunnel, scramble up the rocks, and looking up you can see long tubes. Extending up into the mountain, these tubes are completely lined with minerals like fluorite and galena. As I said, late-stage growth.

Courtesy The Arkenstone

A Glowing Bonus

A final ‘basic’ is that many fluorites are fluorescent. Under either shortwave or longwave UV light, many fluorites will glow brilliantly.

It could be from trace elements in the mineral or possibly even organic material, but the effect can be amazing. By the way, the term ‘fluorescence’ is actually derived from the English fluorite’s mineral name and not the other way around.

A World Tour

We are fortunate that fluorite is a relatively common mineral that leans toward the beauty end of the collectible mineral spectrum. That means there are lots of localities worldwide that have produced quality specimens, and hopefully, there will be more to come. Here are a few areas and a few examples.

Africa has produced its share of great fluorites, many notable ones from Morocco, Namibia and South Africa. The fine green South African octahedrons are markedly different from Namibian fluorites. Many of these are dominantly green, with great variations in colors and patterns within them.

Asia, with China and Russia in particular, has produced a wide variety of fluorites from a wide variety of locations. Dalnegorsk in Russia is known for its water-clear and green fluorites. China and Mongolia have produced many great fluorites with numerous and attractive habits.

The Asian subcontinent, as well, has produced outstanding fluorites, particularly from Pakistan and India. Pakistani fluorites can be pink with hints of green, and they are often associated with great minerals like aquamarines. Indian fluorites can be golden or tinted red and they tend to be spherical. Combinations there, as well as singles, can be mind-blowing.

Europe, with its long history of mining and collecting, has produced many many great fluorites. Spain, Germany, England, Switzerland and France are but a few countries that leap to mind. English fluorites, Switzerland/France (Alps) have their world-class and highly-coveted pinks, Spain has multiple colors and France its gold and blues (separately or together).

North America is home to many famous fluorite locations, be they in Canada, Mexico, or the U.S. To even try to list colors and localities would take a book, but just focusing on those alone could surely make a superb collection. There are many wonderful fluorites to be had and there are even some rare and desired fluorites from Mexico that actually fluoresce red.

In South America. Peru is long famous for its pink with green fluorites, and it is now producing high-class greens. Brazil is even getting into the act with a recent find of lovely, medium-blue fluorites.

Photo credits: Joe Budd, Jeff Scovil, Robert Mosley, The Arkenstone, Laszlo Kupi

Finally, Fluorite

So where does the mineral name ‘fluorite’ actually come from, if not from its characteristic fluorescence? It comes from the Latin word ‘Fluere,’ which means ‘to flow.’

One of the first uses of fluorite was as a flux in making steel, aiding the process by helping the molten material flow, and helping purify it at the same time. Fluorite is also used to make glass, enamels, and hydrofluoric acid (please do not use that at home).

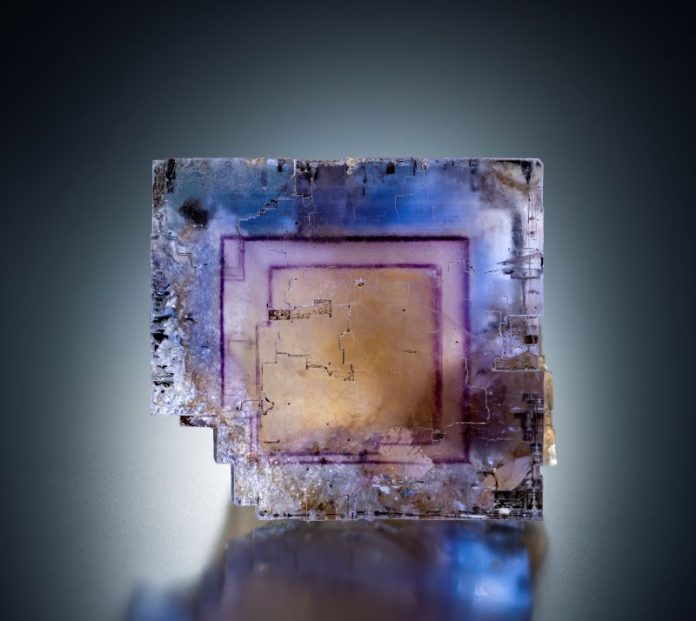

And nobody asked about color? Well, as with many other things, including minerals, trace elements can act as chromophores and cause coloration. For fluorites, some examples include samarium which produces green, oxygen which produces yellow and calcium which produces purple.

Even hydrocarbons can get into the act. But there is a wrinkle. The family of fluorite chromophores can also include some molecules that are aniline dyes, which are akin to amino acids. When it comes to the hydrocarbons and the anilines, the first thing that comes to mind is that ‘anything organic can break down.’ Indeed, some fluorites, even those with simple chromophores, can and will fade in light. This can be true for some other minerals, as well. It’s best to keep minerals in an environment that is relatively UV-free. But when you enjoy your fluorites, oh my, the colors! My license plate says FLRITE. What would yours say?

This story about fluorite previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Jeff Starr.