Explore gem mining in Kenya with a third-generation African rough gemstone buyer named Vter Young. Vter (whose given name is Peter Ngumbi Musomba) spends much of his time traveling around the backcountry of Kenya in search of artisanal miners who eke out a living doing the back-breaking work of digging in the earth for any one of the many gemstone species Kenya and neighboring Tanzania are known for. Here’s a look at the scene through Vter’s eyes.

Gem Mining in Kenya and Tanzania

Geologically, eastern Kenya and adjacent parts of Tanzania consist of a suite of metamorphic rocks called the Mozambique Belt. They are the remnants of a time when Africa, Madagascar, Sri Lanka, and Antarctica were part of a supercontinent called Rodinia.

These rocks are old…really old. The Rodinia continent formed some 1.2 billion years ago and started to break up 700-800 million years ago. All of this geological activity with its resulting extreme heat and pressure at depth gave rise to a complex series of formations that are dominated by gneiss, reworked basement rocks, and pegmatites. Significant faulting allowed hydrothermal processes to enrich the rock formations and pegmatites giving rise to the suite of gemstone species that make east Africa such a magnet for miners and rough gemstone buyers.

The list of gemstone types found in Kenya and adjacent Tanzania is long. It includes several kinds of garnet, tanzanite, tourmaline, sapphires and others. The main gemstone bearing areas are found along a fault that extends from the Taita Hills in Kenya to the Umba Valley in northern Tanzania.

Artisanal Mining

The life of artisanal miners is tough and fraught with the boom-and-bust life cycle that was so much a part of the many gold rushes that occurred in North America.

Few miners actually own the land where they are mining, instead they strike some kind of business deal with landowners. Some give a percentage of what they find to the landowner, while others are provided with tools and food for a percentage of what they find. A lack of mechanization relegates most of the mining activity to hand tools. Sledges, chisels, picks, pry bars, wheelbarrows and shovels are utilized for most of the digging. Gloves, goggles, and work boots are a luxury most cannot afford. Better financed operations might have air compressors, rock drills, explosives and backhoes. The host rock which is dominated by gneiss and schist is tough and gets harder and more resistant with depth so many of the small-time mines tend to be rather shallow pits.

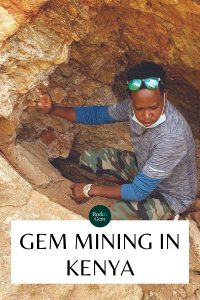

New areas are first explored by checking for signs of mineralization. If any traces of gemstone crystals are found on the surface, shallow pits are then dug to check the potential for starting a mine. Most of the mining operations are either worked by individuals or small teams. After exposing the metamorphic bedrock the miners often tunnel following gemstone trends in the decomposing rock. Most of these tunnels are not braced so cave-ins, dislodged boulders, and wall collapses are fairly common. Miners die each year as they pursue the elusive treasures. It is very dangerous work.

Traveling with Vter

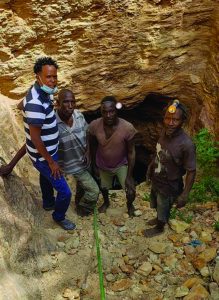

Vter crisscrosses much of the gemstone-bearing areas in eastern Kenya south of the city of Voi and then down into neighboring Tanzania. Vter said he spends extended periods of time based in Voi when on buying trips. The gem fields can be dangerous, so when Vter is in the field he is accompanied by a security manager named Michael and a driver named Philip who arranges all of the transportation. The roads he and his companions travel are often no more than dirt tracks that wind through the acacia-thorn bush. The monsoon season makes these roads impassable.

During an interview for this story, one of the mines Vter visited was a prospect that had been drilled and blasted through 80 feet of solid rock. Another 30 feet of overburden and loose rock above the shaft had first been removed with a track hoe. This mine was being funded by the landowner to the tune of $60,000 and counting. The steep incline into the mine was accessed via a rope.

As he looked down the audit he could hear the sharp staccato hammering of sledge on steel chisels from deep in the dark depths of the tunnel, lit only by flashlights secured to the sides of the miners’ heads. Months of backbreaking work had so far produced little in the way of gemstones. This is the life of miners everywhere. Do you keep digging and hope that a big find is close, or abandon the diggings and find someplace to start over?

The main gemstone rough Vter is interested in is tsavorite garnet. As miners follow mineralized trends in tsavorite-bearing gneiss, the garnets they encounter usually consist of masses of what looks like green aquarium gravel. As stated earlier, after the crystals initially formed at depth tectonic forces crushed them into smaller green glassy bits. This is why finding tsavorite rough larger than a carat is difficult. Once a mass is found it is carefully excavated and hauled to the surface where it is picked apart and sorted.

Miner James Gecago Solomon

A miner Vter buys rough from is James Gecago Solomon. James has been mining gemstones for 30 years and Vter has been his main buyer for the past six years. He is married with two kids and works by himself. During that time the largest tsavorite he has ever found was four grams which pencils out at 20 carats. James doesn’t own the land he mines on, nor does he have a claim. Instead, he has a working relationship with the landowner who is given 30% of what James gets for the tsavorite rough he finds. Day in and day out he toils to find enough rough to support his family. His weathered skin and calloused hands are a testament to his many years working under a hot Kenyan sun pursuing his fortune in the unforgiving gneiss bedrock that hides the green treasures.

Gem Mining in Kenya for the Long Term

Vter has been a rough gemstone buyer for the past 10 years. His family has been in the business for three generations, and Vter learned the business from his father John Ngumbi Mainga and grandfather. This long tradition has allowed his family to make deep connections with artisanal miners all over the gemstone-bearing areas. His family name recognition has afforded him great success in the cutthroat competition of seeking out good rough.

Vter periodically visits miners he keeps in contact with to see what they have been finding and follows up on rumors of large stones being found. He also deals with brokers who have bought rough from miners for resale. When dealing with miners, Vter says he assesses the quality of the rough they have found, offers a price he is willing to pay and then buys everything they have. He says he often pays more for parcels from the miners because they tend to undervalue their finds.

He says that brokers are harder to work with as their asking prices for parcels are usually high so he just makes an offer, they counter, and he says yes or no.

Selecting Rough to Purchase

Selecting the rough Vter would like to buy is a science in itself. Some sellers attempt to prey on inexperienced buyers by trying to pass off pieces of green glass or much less valuable green tourmaline. He said he prices rough by color, clarity, size, and potential yield. Ultimately the price he pays for a parcel will depend on the factors listed above. Because larger crystal pieces are rare they command higher prices.

The dance between sellers and competition between potential buyers can be quite intense at times.

Following Vter

Vter has a Facebook page at www.facebook.com/vter.young that he updates on an almost daily basis where he showcases his gemstone finds as both still photos and video. He also posts parcels of different kinds of gemstone rough he finds. He can be reached by email (vtersyoung@gmail.com) or on Instagram (www.instagram.com/vteryoung/).

This story about gem mining in Kenya previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe! Story by Jim Landon.