Gemstone setting is changing as faceting technology rises to meet the burgeoning creativity of gemstone artists. Jewelry makers are stepping up with new designs, demonstrating a completely revolutionary level of skill and talent.

Master jeweler Mark Farrell of Buffalo Craft Company in Spring Hill, Tennessee explains that traditionally faceted gemstones have five major components — the pavilion, girdle, crown, table and culet, which is the flat bottom of a cut gemstone. When gemstone setting, the stone is held in place at its widest part, the girdle, by a type of metal head or mount.

“The idea is that the seats are perfectly contoured and cut to conform both above (crown) and below (pavilion), the girdle. Most stone setting techniques utilize these three parts in some way, shape or form,” he says.

Unconventional Faceting Challenges

When it comes to concave or carved gemstones, the girdle and pavilion are often not flat, while in other situations the crown is recessed, making the conventional methods practically impossible.

Farrell also points out that in a traditional gemstone setting, the girdle is either faceted or ground to the same regular shape as the stone. This can be round, square, or pear-shaped depending on the piece. Yet, with the concave gemstones, the girdle is often altered or manipulated in some way and new techniques are required to set these dramatically unique gemstones.

“We’re fixturing them in place,” he says. “We’re building a piece to receive the stone. You have to manipulate the stone in a different capacity.”

“In an ideal situation, either the prongs or the bezel (the ring of metal holding the stone in place) would apply pressure evenly over the gemstone. This is why one of the most common settings is the four-prong head,” says Farrell. He explains that when there is a round stone, there are four metal pillars placed at the 1:30, 4:30, 7:30 and 10:30 locations on the stone to hold the gem within the piece.

When it comes to concave and carved gemstones, it’s not possible to follow this standard gemstone setting. “If the gem cutter and lapidarist can think about a stone differently, then so can the jeweler,” he says.

Creating a New Design

Creating a New Design

Farrell says the jeweler needs to find a way to “trap,” or hold the stone, rendering the gem immobile and in one position. Once in place, pressure is applied to specific points, physically keeping it tight and in position. Determining the best method to accomplish this task — all the while showcasing the gem — is the delicate balance of any jewelry artist.

“It’s important to pull apart and understand the ‘why’ of things to develop new ‘hows’ for new problems,” he says.

Farrell says, “Instead of worrying about where the setter now can’t grab the stone and apply pressure, look at it as an opportunity. There are now so many more places and options available. Remember as long as it holds the stone in place, and it stays tight, you’re golden.”

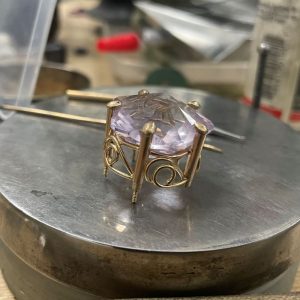

To put these concepts into practice, Farrell describes the setting he fabricated from scratch for the 18.7-carat Rose d’ France Amethyst, cut by lapidarist, Mark Oros. Originally designed by Marco Voltolini, Oros modified Voltolini’s Fiorello 80 design with ULTRA TEC’S Fantasy machine, as part of his faceted flower series.

“Mark did a really nice job with the Fantasy cut, building the design and geometry within the stone,” says Farrell. “It’s tricky when you have a bigger stone because the customer doesn’t want to cover the gemstone. Playing with these Fantasy cut gemstones makes you think differently and forces you to solve the problem in different ways. This is not a normal way of setting stones.”

Creating Form and Function

Creating Form and Function

To capture this eye-catching amethyst, best compliment the stone and create a sturdy elegant gemstone setting, Farrell says, “We utilized the smallest and deepest concave girdle cuts to set this stone. These 2mm diameter cuts were perfect for receiving a 2mm outside diameter tube. Though we did not grab our stone at the widest point of girdle, we did trap the stone, keeping it in one place. The five tubes lock into the girdle cuts on the stone almost like a gear would.”

Farrell’s gemstone setting work is created from raw materials specifically to fit the task. Here he used 24-karat gold and mixed it in a 58.5 to 41.5 percent ratio with an alloy before melting it together in the crucible, creating 14-karat gold, and then poured it into ingots with the precise measurements he required. Once cooled, the round ingots were put through the rolling mill until they were finished to the appropriate size.

“Our next issue that needed addressing was the pressure. How could we apply pressure effectively? Normally pressure is applied by a tool such as pliers or a prong pusher that smashes or moves the metal to its final position over the gem,” Farrell says.

No smashing was needed for this gemstone setting. He created a teardrop-shaped head on a prong to grasp the gemstone in a combination of beauty and function. The tubes were also individually poured and created. To finish the end with the teardrop, Farrell formed the teardrop shape, using the end of an Allen wrench as a mold, and tapped it on the end of the prong to shape the teardrop form.

“The (Allen wrench) punch makes the final desired result, and this way it’s structurally sound,” he points out.

Once the prongs with the teardrop ends were finished, it was a matter of strategically placing them to coordinate with the shape of the stone, and then securing them in place. The tubes were designed to hold the threaded prong tips that bolt in place with tiny, gold nuts, that were also custom-made, to screw onto the end of the threaded prong tip.

“People don’t understand that it is less about making something pretty, it’s about engineering it to fit,” he says. With these three pieces working together, it effectively applies the necessary pressure to keep the stone tightly in place.

He also notes, “Building the setting in this manner allows the top components of the design to be designed and fabricated then put in place, eliminating the possibility of damage to the stone.”

Pros & Cons of the Design

Pros & Cons of the Design

While this seems to work well, the use of screws holding the threaded prongs in the tubes does require certain considerations. On the positive side, Farrell says, “This setting style helps with the placement of the stone. Making the setting in two parts as the stone can be fully top loaded into place without moving any metal, instead of needing to find space to tip or maneuver the stone into its final position. It also eliminates the need to physically mash metal over the stone. The largest benefit of this method is the ability to remove the stone if repair work is ever needed.”

“On the other hand, the use of screws causes some hurdles,” he remarks. Making the mounting with five tiny prongs with long-threaded posts and five tiny bolts, all by hand, means that everything has a final correct placement. Each tiny screw has a corresponding tube, and each tube and screw are different. No two are the same. It is important to keep track and mark parts to keep everything straight.”

When assembling and securing the stone in this custom-made setting, there are a few additional issues to keep in mind. Farrell says, “It is also important to remember that while using screws you have a tremendous mechanical advantage. It is very easy to over-tighten screws in the fitting process. This can be devastating if the result is a smashed or broken stone.” He warns that this can happen very easily, particularly if a jeweler isn’t accustomed to working with this type of setting.

Pulling it All Together

Pulling it All Together

Once everything is constructed down to the smallest detail, the set amethyst is put into the laser welder, which tacks all the parts together so Farrell can finish soldering the piece in one sitting. He notes that Superglue is another option, although the laser welder is a huge benefit for its precision and time-saving capabilities.

For the Rose d’ France Amethyst, he says there were 35 solder seams. “I did the entire piece one at a time. It’s all about working clean,” he says. “The tolerances are straight and tight. Everything is the right size and the rest of it is built in place.”

“I’m making it up as I go,” Farrell laughs, but in reality, every step is carefully calculated to create an elegant effect with the judicious use of materials, resulting in a perfect example of artistic collaboration.

The end result is a dazzling pendant with an expertly cut gemstone that draws in the eye to the depths of an ice-like, purple flower accentuated by the fine gold metalwork that gracefully, yet firmly, cradles the piece. Working with unconventional gemstones such as this allows jewelers to think outside of the box and create an equally stunning setting.

To see the Rose d’ France Amethyst and follow Farrell’s work, go to his website at https://www.buffalocraftcompany.com/, or follow him on social media.

This story about gemstone setting previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Amy Grisak.