What are the gemstones of the Bible? The Bible makes many general references to “precious stones” and “jewels,” most often as metaphors for such attributes as value, wealth, beauty, and durability. It also mentions 23 specific gem materials, among them 20 mineral gemstones and three biogenic gem materials like amber, coral and pearls.

Gemstones of the Bible – Sacred Breastplate

The Bible’s most celebrated – and debated – reference to gemstones regards the sacred breastplate of the high priest of the Israelites, also known as “Aaron’s breastplate” and the “breastplate of judgment.” Described in detail in the Old Testament’s Book of Exodus, this golden breastplate was set with 12 different gemstones arranged in four rows of three gemstones each. Each gemstone was identified in ancient Hebrew, the original language of the Old Testament.

But the text of the original Hebrew Bible and the meanings of many ancient Hebrew words are now largely lost. Our knowledge of the Old Testament as presented in the Bible’s many English versions is based on 2,500 years of scholarly interpretation of Greek, Aramaic, and Latin translations

Gemstones of the Bible – Debating Identities

Not surprisingly, the identities of the breastplate gemstones have become confused. Modern English versions of the Bible collectively offer more than 40 different identities for the 12 breastplate gemstones. Most are modern names of minerals, gemstones and mineral varieties, along with some archaic English names and several untranslated Greek and Latin names.

Adding to the confusion, modern artistic depictions of the breastplate often disregard the probable color and transparency of its gemstones. Many depict the gemstones as faceted, transparent gems, even though faceting as we know it today was not developed until about 1400 C.E. Before the first century B.C.E., most gemstones were opaque or translucent and were fashioned as cabochons.

For centuries, historians, theologians, and scholars have debated the identities of the breastplate gemstones and agree only on the general historical background of the breastplate itself. According to biblical scholars, the Old Testament was written over 1,000 years, roughly from 1400 to 400 B.C.E. The breastplate was created about 1450 B.C.E. during the time of Moses. The Book of Exodus, which contains the breastplate description, is based almost entirely on oral tradition and was written in stages between 600 and 400 B.C.E.

Gemstones of the Bible – Tricky Translations

Most interpretations and translations of the names of the breastplate gemstones were provided by scholars with little, if any, geological, gemological, mineralogical, or sometimes even historical, awareness. Their translations are based largely on tradition, limited gemstone knowledge, personal whim, or simple phonetics – sapphieros must mean “sapphire,” and topazos must means “topaz.”

But Dr. James A. Harrell, Professor Emeritus of Geology at the University of Toledo, has taken a different approach to identify breastplate gemstones. A specialist in the archaeological geology of Egypt and the Middle East, Harrell presents his ideas in a paper published in the Bulletin for Biblical Research and titled “Old Testament Gemstones: A Philological, Geological, and Archaeological Assessment of the Septuagint.”

The Septuagint is a third through first-century B.C.E. Greek translation of the original Hebrew Bible. The name “Septuagint” stems from the Latin septu gint, meaning “seventy” and refers to the number of Jewish scholars who worked on the translation. As a first-generation translation, the Septuagint is the most direct linguistic link to the identities of the breastplate gemstones.

Gemstones of the Bible – Breastplate Order

In his research, Harrell considered all Septuagint passages that mention gemstones and not just those related to the breastplate. He also consulted numerous other contemporaneous ancient texts that describe gemstones that are likely the same as those in the breastplate.

Historically, Harrell considered the gemstones that were known to be in use in the greater biblical region (southwestern Asia, Egypt, and the eastern Mediterranean) during the first millennium B.C.E. He also applied geological criteria to gemstone identification and drew upon his own field research and personal examination of ancient gemstones in museum collections.

As described in Exodus, the order of the breastplate gemstones progresses from right to left, as does ancient Hebrew writing. The first stone in each row, therefore, appears at the right and the third stone in each row at the left. In the following discussion, the stones are identified by the transliteration of their Septuagint Greek names that have so confused translators.

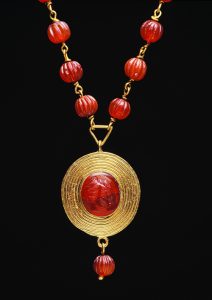

Sardion

Sardion is the first stone in row one of the breastplate. It has been translated as “carnelian,” “sard,” “sardonyx,” and “red jasper.” Archaeological recoveries indicate that carnelian and sard, both translucent forms of microcrystalline quartz, were the most common gemstones throughout the biblical region during the first millennium B.C.E. Carnelian is reddish; sard is brownish. Sardonyx is a brown-and-white-banded type of sard. Red jasper, an opaque form of microcrystalline quartz, also served as a gemstone, but not nearly to the extent of carnelian.

In his Naturalis Historia, the Roman scholar Pliny the Elder (Gaius Plinius Secundus, 23-79 C.E.) describes sardion as a widely used, “fiery, red gemstone.” As a gemstone for the breastplate, Harrell concludes that bright-red carnelian would certainly have been chosen over sard, sardonyx, or red jasper.

Topazos

Topazos is the second stone in row one of the breastplate. Topazos has been translated as “topaz,” “chrysolite,” “emerald,” and “peridot.”

Its earliest reference, written in the second century B.C.E., describes “a delightful, transparent stone similar to glass and with a wonderful golden appearance.” Another calls it “topazion Ethiopias,” meaning “topazos from Ethiopia.” During the biblical period, “Ethiopia” referred to Egypt’s Eastern Desert and nearby Red Sea islands.

Pliny writes that this stone came from the Red Sea island of Topazum (now Zabargad Island). He calls it the largest of the precious gemstones and the only one that is affected by an iron file – a description that indicates topazos is peridot, the gem variety of the olivine-group mineral forsterite (magnesium silicate). At Mohs 6.5, peridot is just soft enough to be scratched with an iron file, unlike the harder emerald and quartz gemstones. And the basalt formations of Zabargad Island, a classic peridot locality, have yielded very large peridot crystals.

Topaz, or basic aluminum fluorosilicate, is much harder than peridot and does not occur in basalt. Topaz was given its modern name in the 18th century when it was confused with the ancient topazos. Harrell is confident that the breastplate’s topazos is definitely peridot.

Smaragdos

Smaragdos is the third stone in row one of the breastplate. Smaragdos has been translated as “beryl,” “carbuncle,” “emerald,” “malachite,” and “turquoise.” In his On Stones, the Greek scholar Theophrastus (ca. 371 – ca. 287 B.C.E.) writes that smaragdos refers to a group of bluish and greenish stones and that it is “good for the eyes,” implying a cool, soothing color. He also mentions that blocks of smaragdos large enough to fashion into obelisks were common.

Emerald was not readily available until mines in Egypt’s Eastern Desert opened in the late first century B.C.E. At that time, smaragdos was also referred to as emerald, probably because of its similar green color. But the size of the smaragdos that Theophrastus describes certainly does not indicate emerald.

Some early descriptions of smaragdos would fit malachite. During the first millennium B.C.E., malachite was mined as the primary ore of copper on Cyprus and the Sinai Peninsula, and in Israel’s Timna Valley. Malachite was associated with such colorful, oxidized copper minerals as turquoise, azurite, and chrysocolla, which sometimes occurred in large, intermixed blocks.

Anthrax

Anthrax is the first stone in row two of the breastplate. Anthrax has been translated as “carbuncle,” “emerald,” “ruby,” “turquoise,” and “red garnet.” The Greek word anthrax refers both to hot embers and to a gemstone with a similar, glowing red color. Theophrastus describes it as “very rare and small, and carved into signets,” and compares its color when held against the sun to that of a glowing, red coal. He notes anthrax being “angular and containing hexagons.” Garnet group minerals, which crystallize in the cubic system, often occur as spheroids with hexagonal faces.

Pliny, who refers to anthrax as carbunculus, notes its “exceptional brilliance.” The substantial density of garnet-group minerals produces a high index of refraction and thus greater “brilliance” than many other red gemstones. Pliny also observes an amethyst-violet tone in the basic red color of anthrax. The almandine-pyrope garnet series, which has purplish-red colors, were the garnets mainly used in antiquity. Although garnet was occasionally found in the biblical region, most came from India after the third century B.C.E. Harrell concludes that the breastplate’s anthrax is red garnet, most likely a member of the almandine-pyrope garnet series.

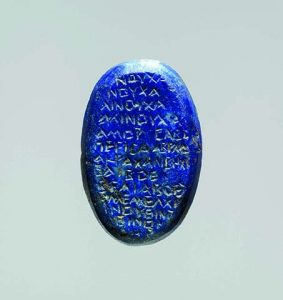

Sappheiros

Sappheirosis the second stone in row two of the breastplate.

Sappheiros, the origin of our modern word “sapphire,” has been almost universally translated in the Bible as “sapphire.” Yet sappheiros is actually lapis lazuli, a prized gemstone and a major trading commodity throughout the biblical period.

B.C.E.: Scholars agree that the

Septuagint’s sappheiros is lapis lazuli.

(Wikimedia

Commons)

Lapis lazuli is a metamorphic rock consisting of lazurite, calcite, pyrite, and other minerals. Lazurite, a basic sodium calcium aluminum sulfate chlorosilicate, is the primary mineral in lapis lazuli and the cause of its striking blue color. In top-quality lapis lazuli, pyrite appears as glittering, disseminated specks. Many ancient writers have compared the dark-blue color and glittering pyrite specks of sappheiros to a star-filled night sky.

Since 4000 B.C.E., the Sar-e-Sang mines in northeastern Afghanistan have produced the world’s finest lapis. The corundum gemstone we now know as sapphire was not available in the first millennium B.C.E. Had it been available, its extreme hardness would have made it very difficult to work.

There is no doubt that the breastplate’s sappheiros is not sapphire, but lapis lazuli.

Iaspis

Iaspis is the third stone in row two of the breastplate.

The Bible’s long list of iaspis translations include “beryl,” “diamond,” “rock crystal,” “emerald,” “jasper,” “onyx,” “moonstone,” “chrysoprase,” and “amazonite.” Theophrastus writes that iaspis was carved into seals, and groups it with smaragdos, implying that it has a bluish or greenish color.

Pliny describes it as “a highly prized stone,” translucent and with blue and green varieties. Although these descriptions are general, iaspis could be greenish microcrystalline quartz, perhaps a color variation of jasper. Iaspis is also the origin of the modern word “jasper.”

But another possibility is amazonite, the green-to-blue variety of microcline feldspar, which was mined in Egypt during the first millennium B.C.E. and saw limited use as a gemstone. However, Harrell believes that iaspis is more likely a greenish microcrystalline quartz, perhaps a form similar to chrysoprase.

Ligyrion

Ligyrion is the first stone in row three of the breastplate.

Although ancient literature consistently indicates that ligyrion is amber, a fossilized tree resin, it has also been translated as “zircon,” “tourmaline,” and “opal.” The ancient Greeks knew ligyrion as elektron and were aware of its electrostatic properties. Rubbing ligyrion with wool cloth produces a strong negative electrostatic charge that attracts feathers and other light, positively charged materials.

Theophrastus writes that elektron is found in Liguria, an area of northwestern Italy and southeastern France, where it is “dug from the earth” and “has the power of attraction.” Other writers use the words elektron and ligyrion interchangeably.

In his Naturalis Historia, Pliny notes the sources of ligyrion, which he calls sucinum, as Liguria and the “northern sea” – the latter referring to the Baltic Sea coast. The Baltic coast supplied the Roman Empire with large quantities of amber and remains the world’s most prolific amber source.

Some biblical historians have translated ligyrion as yellowish or brownish zircon; others as tourmaline, likely because of tourmaline’s electrostatic properties. But neither zircon nor the tourmaline-group minerals were used as gemstones during the first millennium B.C.E., whereas amber was common. Harrell believes that ligyrion is definitely amber.

Achates

Achates is the second stone in row three of the breastplate.

Achates has usually been translated as “agate,” which is almost certainly correct. In On Stones, Theophrastus discusses achates as “a handsome stone from the river Achetes in Sicily that fetches a high price.” The Achetes River (now the Drillo River) is the root of the English word “agate” and a classic agate locality.

Pliny describes different colors and patterns of achates, all of which fit agate. He also writes that achates “was once held in high esteem, but now enjoys none,” apparently indicating that formerly valuable translucent and opaque gemstones had fallen out of favor in Rome by the first century C.E. and had been replaced by transparent stones from India.

Amethystos

Amethystos is the third stone in row three of the breastplate. (row three, third stone)

amethystos is amethyst. (Steve Voynick)

The Greek word amethystos, the root of the English word “amethyst,” has been translated only as amethyst and has no conflicting identifications. Amethystos means “without drunkenness;” the stone was believed to prevent drunkenness or to alleviate its unpleasant aftereffects.

Theophrastus discusses amethystos as “transparent … with the color of red wine … and found by splitting certain rock.” This description fits amethyst, because red wine is actually purplish-red, and amethyst often occurs in geodes that must be “split.” Pliny describes the stone as “violet” and notes that it comes from Egypt, where the Abu Diyeiba mine produced amethyst throughout the first millennium B.C.E. The ancient descriptions of amethystos can only fit amethyst.

Chrysolithos

Chrysolithos is the first stone in the fourth row of the breastplate (fourth row, first stone). Chrysolithos has been variously translated as “topaz,” “beryl,” “citrine,” “peridot,” “chrysolite,” and “yellow chalcedony.” The Greek word chrysolithos means “golden stone.” The first-century BCE Greek historian Diodorus Siculus notes its “golden color” and also warns of a “false chrysos” produced by heating—a clear reference to the ancient process of heat-treating amethyst to produce citrine (golden quartz). Pliny describes chrysolithos as a “bright, golden, transparent stone” from Egypt, where amethyst was likely heat-treated to make citrine at the Abu Diyeiba amethyst mine.

Some historians suggest that chrysolithos is actually yellowish-green peridot, which was once called “chrysolite,” from the Red Sea island of Zabargad. But the breastplate would not have two peridot stones, even under different names. And no archeological evidence supports citrine’s use as a gemstone before the first century B.C.E.

Others suggest that chrysolithos could be transparent, yellow zircon, also called “jacinth” or “hyacinth.” Yet another suggestion is modern topaz (not to be confused with topazos or peridot). But all transparent, yellow stones recovered from biblical archaeological sites have proven to be citrine. And neither zircon nor topaz, nor any other transparent, yellow gemstone had significant uses during the first millennium B.C.E. Harrell concludes that chrysolithos is probably, but not positively, a yellow chalcedony.

Bēryllion

Bēryllion is the second stone in the fourth row of the breastplate (fourth row, second stone). Bēryllion has been translated as “beryl,” “emerald,” “aquamarine,” “jasper,” “chrysoprase,” and “onyx.” Several of Theophratus’ contemporaries refer to “sparkling little bēryllion” as a “cubic stone.” One mentions “Indian beryllon” as coming from India; another notes its color and shape as similar to those of smaragdos, an ancient synonym for emerald. Pliny notes that bēryllion and smaragdos both have hexagonal shapes, and colors like “the pure green of the sea.” While the “cubic stone” description does not crystallography fit beryl, Harrell suspects that the writer may have used “cubic” as a simple expression for beryl’s well-defined, rectilinear shape. Harrell concludes that bēryllion is probably, but not positively, the aquamarine variety of beryl.

Onchion

Onchion is the third stone in the fourth row of the breastplate (fourth row, third stone). Onchion has been translated as “beryl,” “agate,” “onyx,” and “jasper.” The Greek word onyx means “fingernail,” and the lunula (the crescent-shaped, whitish area at the base of a fingernail) resembles the white bands in onchion. Theophrastus describes onchion as “mixed in color, white and dark alternating,” while Pliny observes it to have “several bands of different colors combined with others that are milky white.” Onchion can be only agate or onyx, two closely related forms of translucent, microcrystalline quartz. Agate has wavy or curvy parallel laminations, while those of onyx are generally straight.

But only onyx was used for the cameo relief carvings that became popular during the late biblical period. As a cameo stone, onchion would have been easily differentiated from agate. India was a major source of onchion from 300 B.C.E onward, and numerous onyx cameo blanks have been found in the ruins of the ancient Egyptian Red Sea port of Berenike, which handled much of the Indian trade. Harrell is certain that onchion is onyx.

While not answering all questions about the identity of the breastplate gemstones, Harrell provides convincing identifications for many of the stones and narrows the possibilities for others. At the least, Harrell’s work provides fascinating insight into the gemstones that were actually in use during the biblical period.

This story about gemstones of the Bible previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story and photos by Steve Voynick.