Editor’s Note: This is the second of a two-part series about examples of geotourism, specifically in Europe. To enjoy the first part, follow this link>>>

By Jim Brace-Thompson

Scotland is, quite literally, the land where modern geology began with a man named James Hutton (1726-1797) and his 1788 tome Theory of the Earth. Until then, the Bible was considered the ultimate source of knowledge in the Western world, and a bishop named James Ussher used it to develop a chronology. Following identifiable dates and extrapolating from generations noted in the Bible, beginning with Genesis, Ussher determined the exact date of Earth’s creation to be October 23, 4004 BC.

Enter James Hutton. Originally a farmer who witnessed first hand erosion processes as he tended his lands, Hutton believed the Earth to be far older. Rather than use the Bible as the ultimate source of Truth with a capital “T,” Hutton believed we should use scientific observation of the world. Following this line of thought, he observed beds of rock resting atop other beds of rock that had been upturned and eroded. Judging by rates of erosion he saw on his farm, he hypothesized that the Earth must be far older than Ussher’s date of 4004 BC. In fact, it had to be older by order of magnitude.

In gathering evidence for his theory, Hutton pointed to several spots, but one in particular has stood out in the annals of geological history: Siccar Point on Scotland’s eastern edge along the North Sea. Here, he identified the processes and cycles that shaped the Earth when he observed gray rocks that had been folded and pushed upright, eroded, then overlaid by horizontal beds of red sandstone.

The amount of time necessary for such a juncture involved, in Hutton’s words, “no vestige of a beginning—no prospect of an end.” John Playfair, who accompanied Hutton on a journey to Siccar Point and helped popularize his theory of the age of the Earth, famously wrote that “The mind seemed to grow giddy by looking so far into the abyss of time.” Thus, Siccar Point played a pivotal role in the history of modern geology. It has been said no geologist can properly die without first making a pilgrimage to this geological wonder.

Given that Nancy and I have entered our sixth decade on this good Earth, and our end is closer than our beginnings, we decided to make such a pilgrimage under Angus Miller’s guidance. He took four other hardy souls and us on a five-mile hike to observe Siccar Point from bluffs above the sea. Then we ventured down to the beach to see ancient Silurian beds of greywacke sandstone from the Iapetus Ocean (a precursor to the Atlantic Ocean) that had been turned vertical by tectonic earth forces. We saw where such beds had been broken up and turned into conglomerate mingled with red sandstone at yet another stop. Finally, we saw more-or-less horizontal beds of the Old Red Sandstone from the Devonian Period of Earth history. Truly, we reached out and touched “the abyss of time,” all thanks to a guided geotour courtesy of Miller and his GeoWalks.

At an increasing pace, others with geology background and scientific expertise are giving similar tours. During a subsequent visit to Scotland, Nancy and I found a flyer in Mr. Woods Fossils’ shop telling about Alistair McGowan’s “Hills of Hame” in Edinburgh (hillsofhame.com).

Through Hills of Hame, McGowan sponsors several educational walks, including ones through the Braids and Blackford Hill of southern Edinburgh, the northern Pentlands, and elsewhere. But what caught my eye was a genuinely unique “Pavement Paleontology” tour.

Nancy and I, along with our daughter and her family, signed up for the tour. It proved to be a two-hour walk through Old Town Edinburgh’s streets to see ancient fossil fish embedded in sidewalk paving stones, ammonites in decorative marble, and other fossils in building stones around the city. Like a true geowalk tour guide, McGowan included local history, for instance pointing out spots where Charles Darwin once took tutorials as a student at the University of Edinburgh and where the 19th century paleontologist and writer Hugh Miller once had his printing presses.

In May 2010, Rock & Gem’s own Bob Jones led an 11-day adventure by bus “arranged specifically for rockhounds and mineral enthusiasts.” The tour was entitled “A Rockhound’s Tour of England,” and Bob’s trip took folks to classic mineral localities within England. Stops in London, Derbyshire, Cheddar Gorge, and Cornwall included geologically significant areas, historically important mines, and mineral collections not normally accessible to the public. The trip even afforded opportunities to do some personal collecting. Although he didn’t call it a geotour, by combining areas of geological significance with a dose of history and culture, Bob’s jaunt certainly fit the definition!

Germany’s Admired Geosite

Just as Bob’s 2010 adventure fit the definition of a geotour, a specific geographic region we’ve visited perfectly fits the definition for a geosite. Before they were married and living in Scotland, my daughter Hannah and her then-boyfriend Peter lived in Germany, and during one trip to visit them, Nancy and I had the opportunity to travel to the fabled Idar-Oberstein region via Germany’s equally fabled autobahn. (With no federally mandated speed limit on that autobahn, hold onto your hat!)

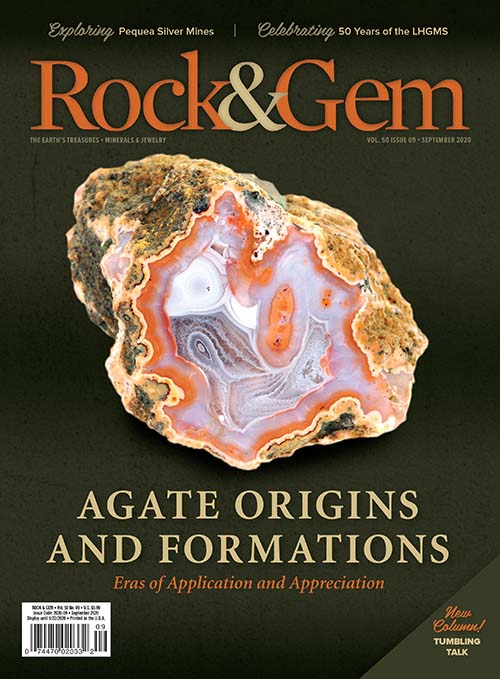

In numerous hand-dug mines and in little mills and lapidary workshops throughout the Idar-Oberstein region, agates had been plucked and worked since before Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue, first using locally sourced agates and then using agates sent from abroad by villagers who had migrated to Brazil.

The gemstone and jewelry industry remains a vital part of the local economy of Idar-Oberstein, and interesting historical spots abound. You can sign up for a guided tour through shafts of the Steinkaulenberg Edelstein (Gemstone) Mine, where agates once were strenuously hammered out by hand. You can visit the Historischen Weiherschleife, a reconstructed gemstone mill where agates were cut and polished using grinding stones 4.5 feet in diameter turned by water power from the river Nahe. And you can stroll through museums like the Deutsches Edelsteinmuseum (German Gemstone Museum) or the Museum Idar-Oberstein glorifying agates and all things lapidary-related.

Idar-Oberstein checks off all the boxes for a proper geosite. The region’s underlying geology and geography shaped its industry, with volcanic rock providing agates and amethyst, sedimentary deposits of sandstone providing immense grinding wheels, and a river providing hydro-power to run those wheels. In short, the region’s geology laid the base for the local economy and influenced a whole culture and way of life, which is now celebrated with tours (group or self-guided) supported by educational placards, visitor centers, and a map to the Deutsche Edelsteinstraße (German Gemstone Road) connecting major historical sites related to the local agate and gemstone craft. And, like a good geosite, the activities of geotourists help support the local economy.

Support For Geotourism

Since 2001, individual geotourists and operators of geotourism businesses have been assisted at an international level. The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) sponsors a collaborative initiative entitled UNESCO Global Geoparks. These efforts involve unified geographical areas hosting outstanding geological sites and landscapes of historical and international significance. A Global Geopark designation helps promote such regions by shining a spotlight on them.

From the beginning, buy-in for park status resides with local communities interested in protecting, enhancing, and promoting their unique geological heritage. And in the end, a Global Geopark should give back to that community via sustainable development that provides for an economic return to the people who live there, be they indigenous peoples, landowners, hotel and restaurant owners, independent operators who develop businesses as tour guides, staff for visitor and interpretative centers, and artisans, or those who provide other services and supplies. The active promotion of employment and regional economic development is especially important in rural and often isolated areas where tourism is a mainstay. Thus, a plan for sustainable employment opportunities is a prerequisite for obtaining Global Geopark status.

Further, via a Global Geoparks Network, individual regions that earn and maintain Global Geopark status enjoy the opportunity to cooperatively exchange best practices within a like-minded community around the world. This community currently includes 147 UNESCO Global Geoparks in 41 countries.

Not long after UNESCO, National Geographic similarly entered the picture, collaborating with destinations and experts worldwide under the banner of geotourism and developing resources to help individual travelers, travel professionals (tour guides, trip planners, travel agents), and local residents of tourist destinations. Their goal is to support authentic, sustainable tourism that is culturally and environmentally responsible.

In 2003, they sponsored a study conducted by the Travel Industry Association of America. Entitled Geotourism: The New Trend in Travel, it found that “55 million American travelers are inclined to exhibit geotourism attitudes and behaviors.” Someone involved with that study must have a sense of humor when you consider how they have divvied up the geotoursim market segments as geo-savvys, urban sophisticates, good citizens, traditionals, wishful thinkers, apathetics, outdoor sportsmen, and self-indulgents. I would hope I might fit within the first group—and certainly not the last!

Although I’d also be happy to be lumped in with the good citizens, i.e., “an older, but wiser set.” They concluded that “geotourism is an emerging trend that will endure.”

National Geographic subsequently developed a set of 13 “Geotourism Principles” that may be found in full on its website. In brief, these include such aspirational goals as respecting the integrity of a place, community involvement and benefit, tourist satisfaction, conservation of resources, and preserving and protecting the destination’s inherent character.

National Geographic works with communities to develop products that will promote and market their area based on local knowledge and needs, or “travel information from the people who live there.” These products include National Geographic Geotourism MapGuides: after soliciting places and themes most recommended by locals, National Geographic has developed and publishes a combination of printed maps, websites, and mobile apps for over 20 destinations worldwide.

Finally, geotourism is even getting incorporated into the academic curriculum as a respectable area of study. Many colleges and universities have long had degree programs in the hospitality industry (hotel, restaurant, and travel administration). Now, you can earn such a degree with a specific focus on geotourism.

Missouri State University pioneered the study when its Department of Geography, Geology, and Planning offered the first-of-its-kind Geotourism minor back in 2010. Others have jumped on board since. For instance, Eastern Michigan University now offers a bachelor’s degree in Geotourism within its Department of Geography and Geology, and Bristol Community College in Massachusetts offers a certificate program in Geotourism Destination Management.

In the June 2018 issue of the journal Geoscience, Rannveig Ólafsdóttir and Edita Tverijonaite of the University of Iceland published a literature review, noting “geotourism is one of the newest concepts within tourism studies today” and that its popularity has “grown rapidly over the past few decades.” They surveyed what has been published about this evolving industry and analyzed trends, concluding a need for a larger body of research focused less on ivory tower “models and methodology” and more on “actual impacts of geotourism…stakeholders and their complex interrelations…and the effects of geotourism on local communities and their well-being.”

From what I understand, no data has been or is systematically gathered to measure the economic impact of geotourism, either locally or as a whole.

In line with Rannveig and Edita’s review, this would seem to be a ripe topic for a dissertation for any student studying such fields as regional economics, geography, or tourism and the hospitality industry. If that’s you, hop to it!

Meanwhile, for the rest of us, stop reading about geotourism, put this article down, and get out there and do it! You’ll be glad you did.

Author: Jim Brace-Thompson

Jim began and oversees the AFMS Badge Program for kids, has been inducted into the National Rockhound & Lapidary Hall of Fame within their Education Category, and is the president-elect for the American Federation of Mineralogical Societies.

Jim began and oversees the AFMS Badge Program for kids, has been inducted into the National Rockhound & Lapidary Hall of Fame within their Education Category, and is the president-elect for the American Federation of Mineralogical Societies.

Contact him at jbraceth@roadrunner.com.

If you enjoyed what you’ve read here we invite you to consider signing up for the FREE Rock & Gem weekly newsletter. Learn more>>>

In addition, we invite you to consider subscribing to Rock & Gem magazine. The cost for a one-year U.S. subscription (12 issues) is $29.95. Learn more >>>