Emerald, a variety of beryl, is the birthstone by month for May, symbolizing spring and new life. In the ancient Tibetan calendar, it was the stone for January. But the stone in question is not green, it’s red, and the issue under debate is whether red beryl can really be called red emerald.

Emeralds in History

Tradition has long referred to the green variety of beryl as emerald. The Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE) called it by the Ancient Greek word smaragdos, which is translated as “green gem.” The Egyptians treasured it and were mining it as early as 1500 B.C. in the littoral zone between the Nile River and the Red Sea.

In 1893, Presbyterian researcher George Easton published his Illustrated Biblical Dictionary, in which he claims the actual meaning of smaragdos is “live coal.” Think about that. A live coal is certainly not green—it is red! So, what makes a green beryl an emerald?

Beryl Colors

First of all, each color variety of gem beryl is given a special name. All the gem beryls owe their color to impurities that act as chromophores, replacing the element aluminum in beryl’s chemical formula, Be3Al2(SiO3)6. The designations 2+ and 3+ refer to the degree of oxidation, or loss of oxygen atoms, in a chemical compound.

Light-blue aquamarine gets its color from the electrons of the Fe2+ form of the transition metal element iron. The red wavelengths of light entering the crystal excite the iron electrons, causing them to shift. This makes the complementary blue wavelengths more dominant, and we see the fine blue color. The darker shade of blue in maxixe is caused by the chromophore Fe3+.

Greenish-yellow heliodor and golden-yellow golden beryl get their lovely color when oxygen and iron (Fe2+ or Fe3+ respectively) are present in trace amounts. These trace elements use light energy to shift or transfer back and forth, and in so doing, cause the yellow to orange wavelengths of light to become visibly dominant.

Pink morganite was named in honor of banker, J.P. Morgan, an avid collector of fine gems. The pink shade is due to a trace of the transition metal element manganese, in the form Mn2+. The octahedral arrangement of the manganese determines the amount of energy these electrons need to shift. As light enters a pink beryl crystal, enough of the blue wavelengths are absorbed for the manganese electrons to shift, allowing some red wavelength energies to reflect.

Even colorless goshenite, named after its type locality, Goshen, Massachusetts, contains trace impurities that inhibit color.

Emerald Green & Red?

This brings us to the green variety of beryl we call emerald, a rare and valuable gem. Tradition insists that green beryl is an emerald only when the color of the crystal is caused by a trace amount of the transition metal element chromium (Cr3+) acting as a chromophore in the atomic structure. In rare cases, emerald’s chromophore impurity is a trace of vanadium.

This leaves us with red beryl to explain. This variety gets its fine red color from the manganese form Mn3+. This difference in the oxidation state is the reason for the difference in color between red beryl and pink morganite. Therefore, referring to these two varieties by the same name, morganite, is not appropriate.

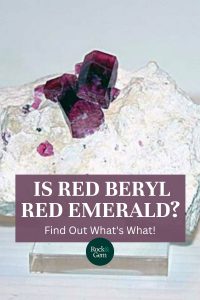

While blue, green, yellow and varicolored beryl is found all over the world, gem-quality red beryl occurs only in the Ruby Violet Claims in the Wah Wah Mountains of Utah. These crystals are extremely limited in size, and rarely can be cut into stones over five carats. Other colored gem beryl crystals have been found in enormous crystal sizes, weighing hundreds of carats, and in a great number of locations. When you consider that most gem beryl varieties have special names, don’t you think gem red beryl should be so honored?

Why don’t we call it “utahite”, since it is found only in that state? Why don’t we call it “wahwahite” after the mountains in which it is found? Unfortunately, these names fail to stir the imagination of gem lovers. Wouldn’t it be more reasonable to recognize red beryl as a very special beryl gem and call it “red emerald”? It is actually rarer than green emerald or any other gem beryl!

The Red Emerald Suite Treasure

Let’s examine the argument for using the term “red emerald.” Seth Rozendaal’s 15-page book, The Red Emerald Suite Treasure, outlines his quest to rename the red beryl of Utah. It is generously illustrated with color photographs of fine red beryl jewelry professionally designed and made to highlight the marvelous gem.

Is it an impossible task to rename red beryl since tradition concerning the chemical composition and color of emerald is so firmly entrenched? What if tradition were not enough to limit our thinking? Why can’t red beryl have a special name?

(David Rozendaal photo)

The Case for Red Emerald

Seth’s arguments in support of the term “red emerald” for Utah beryl crystals are rational, even persuasive. Red beryl of gem quality and in significant quantity has only been known for a few decades, so it has not developed any traditions. Its small crystal size and limited supply has not attracted the same attention that other gem beryl enjoys. Given time, it should.

In Asia, it is paired with green emerald to represent the yin-yang of Chinese philosophy. This pairing lends credence to the idea of the name “emerald” being applied to both red and green beryl.

Seth’s justification for the change is well expressed: “[W]e have not yet invented another title which resonates more resoundingly within the soul of human history to the awesome scarcity and prestige of this breathtaking gemstone.”

Surely, the best argument for honoring these rare red beryl crystals with the name “red emerald” lies in the beautifully created Red Emerald Suite Treasure jewelry.

This story about red beryl appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Bob Jones.