By Russ Kaniuth

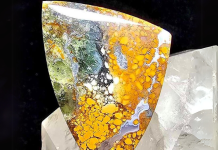

Stichtite is a warm, welcoming stone, with all its wonderful pink hues ranging from light pink and hot pink to lilac and deep purple. Although it’s mined in various places globally, it’s most known from the Stichtite Hill Mine on the island of Tasmania, in Australia’s southern region. In fact, the stone was named after the former manager of the Mine, Robert Carl Sticht.

This material is a carbonate of mainly chromium and magnesium and is relatively soft, falling around 2 on the Moh’s scale. You will often see this material combined with a bright lime green serpentine known as atlantisite, that comes from the same region. Atlantisite, appreciated for its bright contrasting colors, is extremely popular as well in the lapidary world.

Selecting the Right Slab

Shopping for this material can be challenging, as you need the most stable pieces to cut cabochons. Many times stabilization is required to cut it at all. The other option is to back the material and make a doublet, but that brings up the issue of matching colors or having a cab with an additional color backer. Atlantisite is no different; most of the time, it also needs to be stabilized or backed.

Once you are ready to cut slabs of stichtite, it’s always best to examine the material thoroughly for any visible fractures and even try and pull them apart gently by hand. It’s better to have it fall apart first, versus in the saw.

When you know what you are dealing with upfront, you can make a better game plan to cut it to maximize your material.

Cabbing this material can be somewhat tricky, and I wouldn’t advise it for a novice until after gaining experience cutting extremely soft materials as cabochons. Stichtite can grind away into nothing in seconds flat if you begin with a coarse grit wheel. I would suggest starting on a well used 220 grit steel wheel, and gently preform your cabochon, leaving extra space around the edges, as it will continue to sand off quickly as you proceed through the other grits. If I notice the material is exceedingly soft, I will preform gently on the 220 steel wheel and skip to the 600 grit soft resin wheel.

Usually, most people use a towel to dry the cabochon to check for scratches at this stage. However, since stichtite can be a porous stone and hold moisture and change/darken the color resulting in hidden imperfections, it’s best to use canned air to thoroughly dry it off to check for any remaining scratches before moving on. Once you reach the 1200 grit wheel stage, where jaspers and agates typically receive a polish, continue to use gentle pressure, as it will help remove material even at this fine grit due to the material’s softness.

Once you’ve run your routine and polish up to either 8000 or 14,000 grit, you should achieve a brilliant glossy polish with a semi-waxy feel to it. With that being the case, there’s no need to attempt any further polishing by using compounds.

Give it a few hours to completely dry to see the final color as it may change slightly once all the moisture has dried out of the stone. Then it will be ready to set into a wonderful and colorful piece of jewelry.

Author: Russ Kaniuth

The owner of Sunset Ridge Lapidary Arts and the founder and operator of the Cabs and Slabs Facebook group. See more of his work at https://www.facebook.com/SunsetRidgeLapidaryArts.

The owner of Sunset Ridge Lapidary Arts and the founder and operator of the Cabs and Slabs Facebook group. See more of his work at https://www.facebook.com/SunsetRidgeLapidaryArts.

If you enjoyed what you’ve read here we invite you to consider signing up for the FREE Rock & Gem weekly newsletter. Learn more>>>

In addition, we invite you to consider subscribing to Rock & Gem magazine. The cost for a one-year U.S. subscription (12 issues) is $29.95. Learn more >>>