King Charles’s coronation jewels take center stage during his official ceremony. What could 350-million-year-old Devonian sediment have in common with the king’s coronation in London’s Westminster Abbey? Amid the glorious sparkle of world-famous faceted gems — set in not one but two ceremonial crowns worn that day — will be a rough-hewn but no less historic symbol of royal rule: A 335-pound, 26” x 16.7” x 10.5” oblong block of Old Red Sandstone, used for centuries in the coronation of monarchs, called The Coronation Stone or Stone of Destiny.

Of Scone and Sandstone

Old Red Sandstone (ORS) extends east across Great Britain, Ireland, and Norway, north to Greenland, and west along the eastern seaboard, sharing similarities in rock type and time of formation with the Catskill Delta of the United States, and as rock hunters might surmise, the red color found in much of its terrestrial rock is indeed evidence of iron oxide.

The Stone of Destiny, or Stone of Scone as originally known, was used for centuries in the coronation of Scottish monarchs until seized in 1296 from Scone Abbey during the English invasion led by Edward I. For the next 500 years, the carved sandstone block was used in the coronation of monarchs for England, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom until the British Government returned it three decades ago to Scotland for safekeeping (when not in use for coronations) with the Scottish Crown Jewels.

The return of this red sandstone block to Scotland was the subject of the 2008 film, Stone of Destiny, and in 2010 in The King’s Speech, Lionel (Geoffrey Rush) sits in the Coronation Chair and props his feet on the Stone of Destiny to provoke King George VI.

Last September, Historic Environment Scotland announced the Stone of Destiny could briefly return to Westminster Abbey for the coronation of Charles III. To slide beneath the seat of the freshly-restored and oil-consecrated Coronation Chair, or King Edward’s Chair, the oldest dated (1296) piece of English furniture made by a known artist (Walter of Durham) in the world, where its ancient red sandstone will bear witness to a new century’s congregation as they shout, “God Save the King.”

Saint Edwards Crown

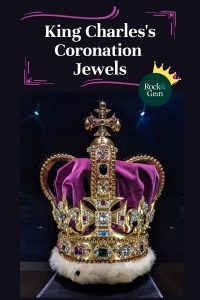

Speaking of Edwards, the centerpiece of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom, and the first of two crowns you’ll see during the coronation is Saint Edward’s Crown, commissioned in 1661 from Royal Goldsmith, Sir Robert Vyner, for Charles II, after the preceding 7.6-pound medieval Tudor Crown, set with 168 pearls, 58 rubies, 28 diamonds, 19 sapphires, and two emeralds, was broken up, by order of Olive Cromwell, during the English Civil War.

and later British monarchs, and one of the senior Crown Jewels of Britain, during a service to

celebrate the 60th anniversary of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II at Westminster Abbey

in London on June 4, 2013. AFP PHOTO / POOL / JACK HILL (Photo by JACK HILL / POOL

/ AFP) (Photo by JACK HILL/POOL/AFP via Getty Images)

Perhaps its commissioner should have taken a better hint from the fate of that earlier crown, for its valuables were sold or melted down after the abolition of the monarchy in 1649 by Parliament, and Charles II was convicted of treason and executed on January 30, 1649, outside the Banqueting House in Whitehall.

In May 2023, Charles III joins just six monarchs since his 1661 namesake was crowned with Saint Edward’s Crown, including James II (1685), William III (1689), George V (1911), George VI (1937), and his mother, Elizabeth II (1953).

The Archbishop will place Saint Edward’s Crown on his head during the investiture, when the sovereign is presented with items symbolic of his role, including the Sovereign’s Sceptre (justice and mercy) and Royal Orb (religious and moral authority).

Edward VII and Queen Victoria eschewed the weighty Saint Edward’s Crown for their coronations, in favor of the lighter, 1838 baroque Imperial State Crown (which also makes an appearance in this coronation). At nearly five pounds, Saint Edward’s Crown weighs the equivalent (as The Washington Post noted) of a gallon of ice cream or $100 worth of quarters. The solid gold crown has 444 precious and semi-precious stones, including 345 rose-cut aquamarines, 37 white topaz, 27 tourmalines, 12 rubies, seven amethysts, six sapphires, two jargoons, one garnet, one spinel, one carbuncle. Jargoons? Carbuncle? Also called jargon (from the Persian, zargun, “as gold”), jargoons are zircons (a mineral belonging to neosilicates) fine enough to cut as gemstones but lacking the preferred red “hyacinth” color. Golden jargoons can be mistaken for tourmaline, but their refractive indices (light bending ability) are higher.

Legend sometimes describes the carbuncle “like a firefly in the night” and when this deep red almandine gemstone is cut with a smooth, convex face (cabochon), that internal brilliance leaves the little question of why medieval texts described it as a stone with magical properties, including the ability to light up dark interiors. The 11th century Journey of Charlemagne describes, “Within it a golden column, and for light a carbuncle stone in its end, making it always a day when the day was gone.”

“It’s absolutely ravishing,” Anna Keay, author of The Crown Jewels and director of the Landmark Trust, said of this coronation piece in a media preview. “It’s this ancient object, the old gold with this lovely, enameled look, and the colors around each of the stones are really beautiful. “I think it stands apart from all the other things in the collection. Because it’s not about the bling, the big diamonds, it was made for an institution that still exists and it is still used for the same job (to coronate a British king or queen), which is incredibly rare.”

The Imperial State Crown

Toward the end of this coronation ceremony, the Saint Edward’s Crown will be replaced with the Imperial State Crown, set with a 317-carat diamond known as the Cullinan II or “Second Star of Africa,” that was cut from the largest diamond ever found and presented to Edward VII for his 66th birthday by the former British crown colony of Transvaal (now South Africa).

If these Crown Jewels look familiar, they should. The last time we saw the Imperial State Crown was atop Queen Elizabeth II’s coffin as she lay in state and its sparkle tells the stories of thousands of gemstones collected over centuries by British monarchs.

The Imperial State Crown has 2,901 gemstones, of which 2,868 are diamonds, plus 273 pearls, 17 sapphires — including the Saint Edward’s Sapphire and Stuart Sapphire — 11 emeralds, and five rubies, including the Black Prince’s Ruby.

Cullinan II – A cushion-cut brilliant diamond with 66 facets, weighing 317.4 carats and held in place by a yellow gold enclosure screwed to the front, below the Black Prince’s Ruby. Still dazzling in its imperfection, it bears a small chip at the girdle.

Saint Edward’s Sapphire –Set in the center of the crown’s top cross and believed worn as a ring by Saint Edward the Confessor, it was discovered in his tomb in 1163.

Stuart Sapphire – A 104-carat blue sapphire said to have belonged to Charles II and moved (1909) to the back of the crown to make room for Cullinan II.

Black Prince’s Ruby – This 170-carat irregular cabochon red spinel is also known as the “Great Imposter”(spinels have magnesium, which rubies lack). Among the oldest parts of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom, it dates to 1367 when it was worn by the Black Prince, Edward of Woodstock, and is said to have also deflected a fatal blow in battle meant for Henry V at Agincourt.

by the Imperial State Crown, in the House of Lords chamber, during the State Opening of

Parliament, at the Houses of Parliament, in London, on May 10, 2022. (Photo by Alastair

Grant / POOL / AFP) (Photo by ALASTAIR GRANT/POOL/AFP via Getty Images)

At 2.3 pounds, the Imperial State Crown is half the weight of its coronation cousin, but could still earn a good-natured quip from Her Majesty, who chose to wear it each year for her State Opening of Parliament.

“You can’t look down to read the speech,” she said about addressing Parliament while wearing it. “You have to take the speech up because if you did, your neck would break, it would fall off. There are some disadvantages to crowns, but otherwise, they’re quite important things.”

We may never be Royals but with a little shine to our stones (and maybe a marmalade sandwich in our Launer handbag), we can all write our destiny.

This story about the coronation of King Charles III is by LA Sokolowski. Click here to subscribe.