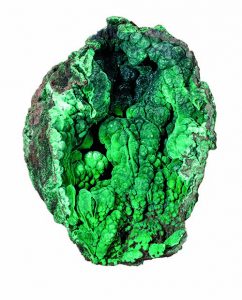

Malachite doesn’t occur in wonderful prismatic transparent crystals like most minerals. Its crystals are tiny, acicular or needle-like crystals clustered so tightly the mineral is found mainly as a solid banded pattern.

Malachite’s most redeeming feature is its green color, which varies from light green to almost black. When solid, It can take a high polish and is held in such high regard it is found in some of the many gorgeous works of art and royal homes. A case in point is the championship cup awarded to Team USA, winners of the Women’s World Cup soccer tournament. Take a close look at that impressive trophy. The base is made of, you guessed it, malachite!

Mining Malachite

At major shows and in museums, I’m sure you have admired the superb gem boxes, a fine lapidary art form designed by my friend Nicoli Medvedev. His creations are featured in many major museums and personal art collections.

The reason malachite has not been used more in works of art and in the decorative arts is its lack of availability. Our copper mines only produce limited amounts of malachite as a secondary mineral. Malachite simply was not found in overwhelming amounts, so access to this gorgeous mineral showing wonderful curving bands of varying green colors was severely limited.

Ural Mountain Mines

That changed dramatically in the 1800s, when a copper mine near Nizhny Tagil, within the Ural Mountains region, began producing lovely banded green malachite in huge (more or less) solid masses. Some of these pieces weighed several tons.

Russian royalty took full advantage of this amazing find, and the Russian art lapidary industry created significant quantities of amazing art objects using malachite. Now known as Russian malachite mosaic, gorgeous creations of malachite are displayed all over the world. Two of the most popular destinations are the malachite rooms in Saint Petersburg’s Hermitage Museum and the Castillo do Chapultepec in Mexico City.

Both rooms are done with Russian malachite. Add to that the hundreds of vases and art objects created with Russian malachite on display in dozens of mansions and official residences, including in Washington, D.C, all these beautiful green art objects are made of Russian malachite.

Plenty of Malachite

Such a remarkable use of malachite could only happen when mined in huge pieces in nearly limitless quantities. Now it has happened again. The vast Copper Basin of Central Africa that runs from Zambia to the Democratic Republic of the Congo is literally disgorging tons and tons of this gorgeous copper mineral. There are dozens of mines producing copper minerals today, much of it malachite. Go to any mineral show and you’ll see someone selling malachite in quantity. This has never happened in the nine-plus decades I’ve been alive. There is no question these really are the halcyon days of malachite when artists and collectors can take full advantage of the quantity and variety of malachite available.

Such a remarkable use of malachite could only happen when mined in huge pieces in nearly limitless quantities. Now it has happened again. The vast Copper Basin of Central Africa that runs from Zambia to the Democratic Republic of the Congo is literally disgorging tons and tons of this gorgeous copper mineral. There are dozens of mines producing copper minerals today, much of it malachite. Go to any mineral show and you’ll see someone selling malachite in quantity. This has never happened in the nine-plus decades I’ve been alive. There is no question these really are the halcyon days of malachite when artists and collectors can take full advantage of the quantity and variety of malachite available.

Malachite is a secondary copper mineral found in the upper oxidized zones of copper deposits. In this country, it was found mainly in deposits of copper porphyry or nearby hydrothermal deposits as a secondary ore. The quantity of malachite has always been limited and spotty and was found mainly as small seams and masses and mined in relatively small amounts. Such malachite never challenged the status of the Russian discoveries. In such small amounts, this has certainly limited the creative artist’s use of this lovely mineral.

Large Malachite Specimens

Why is it that in the last couple of decades I’ve seen large quantities of fine malachite specimens that are so big I can’t even lift them? During these last couple of decades, when I’ve gone to mineral shows, there have always been at least one or two dealers whose tables are loaded with dozens and dozens of malachite specimens in every form and size. For sale are big chunks of velvety malachite, heavy botryoidal specimens, along with dozens of attractive polished malachite specimens in every size, shape, and form. Where has all this wonderful green, often gemmy malachite, come from?

To answer that question, we have to go back more than 100 years when geologists and mineralogists were first prospecting in Central Africa. As this region slowly opened for exploration, hearty prospectors from Europe saw copper artifacts and copper ornaments adorning the locals. The discovery of copper deposits was at hand.

Among these adventurers were men like Frederick Burnham, who was exploring in what was then North Rhodesia now Zambia. As Burnham was prospecting in the very late 1800s, he made an accidental discovery of a copper deposit that gave its name to the entire region, Roan Antelope. Burnham started a copper mine, which he named Roan Antelope. He discovered the deposit when he shot a roan antelope, and while he retrieved the carcass, he came upon a copper deposit.

Called by Copper Deposits

Years later, another adventurer arrived in the region, Alfred Chester Beatty. Beatty was born in New York to a family that was well off. By age ten he had developed a love of minerals, so after college, he went to Colorado and worked the mines. He ended up in Cripple Creek and came away with a fortune and a case of miners’ lung disease. After becoming an English citizen, he went to what he later called the Roan Antelope Belt in Central Africa and invested in copper mines and increased his fortune, eventually building a beautiful museum in Dublin, Ireland.

Years later, another adventurer arrived in the region, Alfred Chester Beatty. Beatty was born in New York to a family that was well off. By age ten he had developed a love of minerals, so after college, he went to Colorado and worked the mines. He ended up in Cripple Creek and came away with a fortune and a case of miners’ lung disease. After becoming an English citizen, he went to what he later called the Roan Antelope Belt in Central Africa and invested in copper mines and increased his fortune, eventually building a beautiful museum in Dublin, Ireland.

Roan Antelope Belt

What Beatty called the Roan Antelope Belt others called the Copper Belt or Copper Basin. It proved to be phenomenally rich in copper deposits. Geologically, the area is the result of the Albertine Rift, a huge displacement of the earth’s crust that started over a half a billion years ago. Simply stated, the basin over the ensuing millions of years was slowly invaded by mineral-rich waters from the surrounding regions.

These waters deposited minerals in the layers of sedimentary sandstone and shale as what we call stratiform deposits, containing more or less horizontal zones of copper minerals.

Such deposits are completely different than the porphyry copper deposits and hydrothermal deposits we have in the U.S. The copper deposits are relatively shallow, subject to constant oxidation producing, in this case, huge tonnages of copper carbonate, malachite. How many tons? The nearly forty miles in the entire vast region from Zambia to the southern Democratic Republic of Congo report copper production of many tens of thousands of tons annually. How much of this is malachite? I have no idea but judging from what I’ve seen of the mineral market in recent years, we will enjoy malachite for years to come.

Changing Hands

The Roan Antelope Belt was first acquired mainly by Belgium in 1908 and was called the Belgium Congo. Deposits in the Katanga region in the southern part of the country were worked by Belgium. King Leopold II of Belgium loved minerals, and as the mines developed, he assembled a huge collection of representative specimens. Eventually, his collection was installed in the Royal Museum for Central Africa at Tervuren, Belgium. I had made arrangements to visit that Museum with my good friend Gilbert Gauthier, but before we could, Gilbert passed away.

As the country of the Congo changed hands again and again through wars and disputes, its name changed. The turmoil interfered with mining development to a great degree, so mineral specimen production was often limited, and the mineral market reflected this. You may remember the region was known as Zaire starting in 1971 but that only lasted until 1997 when the Democratic Republic of the Congo was formed. Now it seems mining in this region is going full tilt.

An Uncommon Sight

Gauthier worked in the region, and when he retired, he sold his mineral collection to dealer Scott Williams, with whom I’ve spent countless hours. Of all the great specimens in that collection, I helped unpack I remember one malachite in particular. This malachite was a stalactite, a fat short stalactite about eight inches high and about four inches thick. It was polished beautifully, showing light to dark bandings. As I marveled at this green beauty, Scott told me to grasp the top and lift, so I did. Surprise!

The whole top of the dome layer lifted off, and under it, the remaining rounded stalactite was also polished. The pieces fit together perfectly. This uncommon sight came to be during the formation of another mineral. Perhaps copper oxide had dusted over the end of the stalactite so when the next layer formed, the bonding between layers was weak and easily separated. I handled that piece perhaps 30 years ago, and it was my introduction to Congo malachite. Little did I know, miners were just beginning to hit zone after zone and mile after mile of malachite in just about every form imaginable.

There is actually no estimate of how much malachite has been mined here and what remains in the Copper Basin. Tonnage estimates just don’t give us a clear idea. Thousands and thousands of malachite specimens are pouring forth constantly. No wonder at every show I see tables loaded with huge quantities of lovely green specimens, many polished, many natural, many hand sized, and plenty of pieces measuring a foot and more across.

Honoring Family With Malachite Donation

To give you just one modest example of a Congo malachite, my family recently donated a  malachite specimen in the name of my late wife and mother of our children, to the University of Arizona Gem and Mineral Museum. My wife Alicia was a graduate of the university, class of 1949. She was also a member of Alpha Phi and a pilot who belonged to the University Flying Club. We thought she ought to be remembered in the new university museum, so we donated a gorgeous malachite as a memorial to her. You can see it when the Museum opens. You can’t miss it as it is no ordinary cabinet specimen of malachite. It stands about 30 inches high and over a foot across, and is very highly polished, to expose a whole suite of bands of varying green color with many classic malachite bull’s eyes. It also weighs in at a respectable 352 pounds.

malachite specimen in the name of my late wife and mother of our children, to the University of Arizona Gem and Mineral Museum. My wife Alicia was a graduate of the university, class of 1949. She was also a member of Alpha Phi and a pilot who belonged to the University Flying Club. We thought she ought to be remembered in the new university museum, so we donated a gorgeous malachite as a memorial to her. You can see it when the Museum opens. You can’t miss it as it is no ordinary cabinet specimen of malachite. It stands about 30 inches high and over a foot across, and is very highly polished, to expose a whole suite of bands of varying green color with many classic malachite bull’s eyes. It also weighs in at a respectable 352 pounds.

The Rice Northwest Gem and Mineral Museum, located in Hillsboro, Oregon, also has another of our donated malachite specimens. The modest 150-pound or so, all-natural, not polished specimen is the classic botryoidal form of malachite that varies from light to dark shades of green.

As you walk around mineral shows these days and come across a few tables loaded with beautiful green malachite, count your lucky stars, because like every mineral that comes from the earth, the supply is finite, though you may not believe it now. Take advantage of the availability of Central Africa’s largest and select malachite specimens that show this mineral’s forms and variety of color. It really is one of nature’s most beautiful minerals.

This story about malachite previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe! Story and photos by Bob Jones.