Marble rock has stood out through time even with the abundance of natural stone materials such as alabaster, travertine, granite, limestone and soapstone, that sculptors and architects have to use. For the last 2,500 years, marble rock has been chosen for many of the greatest works of sculpture and architecture, from the Parthenon of Classical Greece to Michelangelo’s Pietà and Washington D.C.’s Lincoln Memorial.

Durable yet soft enough to be workable, marble occurs in both solid and patterned colors from snow-white to a rainbow of soft pastels. With its fine grain, marble takes a gleaming polish and can be worked in great detail.

Because marble occurs in massive formations, it can be quarried as blocks suitable for the largest sculptures and most ambitious architectural applications. To many sculptors, marble’s most appealing quality is its slight translucency which imparts a subtle glow to the polished stone.

Marble Rock – Out of Limestone

For all its beauty, marble originates as drab limestone, a common sedimentary rock that forms through the accumulation of shells, coral and other organic materials. Limestone consists primarily of the calcareous carbonate minerals calcite (calcium carbonate) and/or dolomite (calcium magnesium carbonate).

Most limestone is dark gray in color; higher grades containing more than 70 percent carbonates have lighter-gray colors. With its dull luster and poor polishing qualities, limestone is not a particularly attractive rock. But because of its abundance and low cost, it is widely used for exterior building blocks. Its biggest use, however, is as the raw material for manufacturing Portland cement.

When subjected to metamorphic heat and pressure, high-grade limestone undergoes a dramatic change. It first takes on a plastic consistency as its fine-grained, crystalline structure is destroyed and many of its impurities driven off. Then, with reduced heat and pressure, this plastic mass recrystallizes as marble with a substantially higher carbonate content and a structure of interlocked grains of translucent calcite and/ or dolomite.

The Magic of Marble

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Marble rock is softer, denser and more durable than limestone. The purest marble, which forms only from high-grade limestone, consists almost entirely of carbonates: snow-white in color, it has a glittery, crystalline texture.

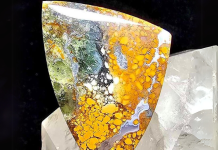

Most marble, however, contains varying amounts of accessory minerals that impart pale colors. Hematite (iron oxide) creates pale shades of red, pink, yellow, brown or green. Carbonaceous material produces gray or blackish colors. Uneven distribution of impurities before final solidification creates attractive “marbled” patterns of swirls and veins.

The slightly luminescent glow of fine marble is because of calcite’s low refractive index which enables light to penetrate the stone before scattering in all directions and reflecting back to the surface. These internal reflections produce the characteristic “waxy” look of fine marble and impart a warm, almost lifelike appearance to sculptures.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Marble of Classical Antiquity

Quarried from Mount Pentelicus near Attica and the island of Páros, marble rock was first used extensively in art and architecture in Classical Greece about 500 B.C. The Parthenon, the crowning architectural achievement of ancient Greece, was built around 440 B.C. The extensive use of white marble in the huge temple symbolized the wealth and power of Athens, the Grecian capital. Perhaps the best-known Grecian marble sculpture, created during the later Hellenistic Period, is the Venus de Milo, which is thought to represent Aphrodite, the Grecian goddess of love and beauty.

The Romans obtained marble rock from many sources, most notably the great quarries at Carrara in today’s northern Italy. Familiar examples of marble in Roman architecture are the 100-foot-high Trajan’s Column and the Column of Marcus Aurelius, both with highly detailed relief panels. Among the better-known Roman marble sculptures are a depiction of Mars, the Roman god of war, and the remarkably realistic busts of a succession of emperors.

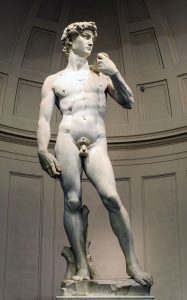

Thanks largely to the work of the great Italian sculptor and painter Michelangelo, marble sculptures regained popularity in Europe during the Renaissance. Of his many marble sculptures and relief panels, the Pietà and David are the most familiar. Michelangelo often visited Carrara to personally select the “perfect” blocks of marble in the exact sizes, shapes and colors that he needed for his work.

Courtesy of Steve Voynick

Colorado’s Yule Marble Rock

Yule marble, arguably the world’s finest white marble, comes from a remote quarry at an elevation of 9,300 feet in the Colorado Rockies. Its highest grade has a remarkable calcite content of 99.5 percent and a color described as “blinding white.”

First quarried in 1887, Yule marble soon attracted attention as the flooring of Colorado’s new State Capitol Building in Denver and experts equated its beauty, color and flawlessness with that of the finest Carrara marble. In 1912, the United States National Commission on the Fine Arts specified Yule marble for the 36 fluted columns, each 46 feet high and seven feet in diameter, of the Lincoln Memorial.

In 1928, after Yule marble was specified for the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, a 75-man crew spent a year quarrying a 124-ton block. When trimmed and polished, the block of “blinding-white” marble was emplaced at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia, in 1932.

The Yule Quarry closed in 1942, but reopened in 1992 and is operating today. Also still producing are several historic quarries in Greece and the famed quarries of Carrara, Italy — all testimony to the fact that fine marble, the beautiful rock that seemingly was magically transformed from common limestone, is still the preferred medium of master sculptors and architects around the world.

This story about marble rock and its uses appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Steve Voynick.