Microfossils were nestled within a pasture in rural New South Wales, Australia, where rolling fields meet endless skies and an unsuspecting farmer named Nigel McGrath found himself on the brink of a remarkable discovery. As he toiled to remove one of several large, heavy rocks that threatened to damage his farm equipment if left in place, he noticed the fossilized imprint of an ancient leaf. He spotted several more as he continued clearing the rocks from his field.

Word of his finds serendipitously reached a team of paleontologists who were traveling through the area on the way to a nearby Jurassic fossil site. Intrigued, the scientists stopped by the farmer’s field to examine the unwieldy rocks. Soon they learned that the fossils the farmer noticed on the outside of these rocks were just a small glimpse of the treasures the rocks contained.

“Since the discovery of this new, more exciting site, we’ve never been back to the Jurassic site we were initially traveling to” said Michael Frese, an associate professor at Australia’s University of Canberra who co-leads research at the new site.

Crowdsourcing a Geological Treasure Hunt

A small patch of the pasture is now regarded as a “Lagerstätte” – asite that yields exceptionally well-preserved fossils – and called McGraths Flat after the farm owner. The boulders that were previously seen as obnoxious obstacles hold the potential to unravel a chapter of Earth’s history.

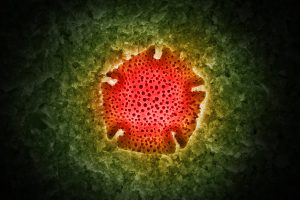

Finding the microfossils each rock contains doesn’t happen the way it’s usually depicted, with paleontologists delicately brushing around the edges of each newfound imprint. “The rocks really get pulverized during these digs,” said Tara Djokic, a researcher at the Australian Museum Research Institute in Sydney, who led a study at McGraths Flat. Many of the fossils are so small they can only be seen with a microscope. “You can use a chisel to split the rocks into tiny pieces and still find fascinating fossils.”

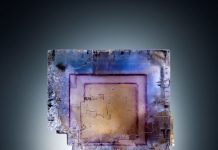

As part of the study, researchers used an electron microscope to automatically photograph the surface of several of the rocks, one small area at a time. It ran overnight and created a mosaic of 3,600 images. The team then repeated the process, ultimately yielding over 25,000 images.

Researchers set out to comb through them in search of different types of pollen and spores that hold clues about McGraths Flat’s past. But while microfossils are relatively common at this site, the team still had to sift through a lot of photos to find them.

So, they enlisted the help of citizen scientists. The project began during the pandemic when The Australian Museum was closed. A virtual fossil hunt provided the perfect opportunity to engage with the public while continuing meaningful research. The collaborative effort brought the wonders of microfossils and larger fossils directly into people’s homes.

“We released the images in bits and pieces like a Netflix series over the course of three and a half months,” Djokic said. “The citizen scientists saved us from looking at 20,000 blank photos by narrowing down the data set to just the 4,000 or so that contained interesting things.” Then they just had to filter through this smaller image set to find the highest quality specimens.

Microfossils: Secrets Entombed in Rusty Rocks

With the help of the amateur fossil hunters, the team identified 300 spores and pollen specimens to perform a detailed climate analysis of McGraths Flat’s distant past and determine the age of the fossils.

They did so using a process called biostratigraphy. Researchers compared the pollen and spores from the site to records from different locations. That allowed them to establish the age of the rocks at the site and create a timeline of the past environments and ecosystems that existed there.

Courtesy Michael Frese

They learned about the area’s past rainfall, the length of its seasons, and even the average temperature at different times of the year, all based on an analysis of long-dead plant material. The team even figured out the site’s longitude and latitude coordinates, which were slightly different from the location’s present position because of the movement of Earth’s tectonic plates.

It’s almost as if the land itself at McGraths Flat whispers tales of forgotten epochs. Those tales are still unfolding as scientists continue to find and analyze more fossils at the site. But already, they know the now pastoral site was once part of a prehistoric rainforest, dating back between 11 and 16 million years – roughly the middle of the Miocene epoch.

Partly because of the type of organisms found embedded in the rocks, including fish, aquatic insects and mollusks, scientists have painted McGraths Flat as the remnant of an oxbow lake formed in a bend of a meandering river that sliced its way through a lush jungle.

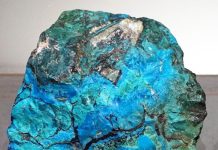

The stagnant lake offered the right conditions for organisms to be wellpreserved millions of years ago. Its limited oxygen circulation made it undesirable for scavengers, so the remains of plants and animals weren’t rapidly decomposed. Since the lake was situated near basalt – iron-rich volcanic rock – it was slowly but steadily injected with iron that washed into the lake when it rained.

That triggered a different sort of rain; little drops of iron fell from the surface of the lake to the bottom, enveloping the untouched remains of dead plants and animals suspended in the water as they fell.

“The specimens at this site are extremely well preserved because of this process, which encased organisms in an iron-rich mineral called goethite,” Frese said. “The discovery is a real boon to paleontology not only because of the wealth of information we can glean from this site but because it hints that additional sites like it are almost certainly to be found elsewhere.”

Microfossils Filling Gaps in the Fossil Record

Relatively few land-based deposits like the one at McGraths Flat are known, which has led to a bias in the fossil record on the side of marine ecosystems. This site offers a rare window into what was happening on the surface of the planet and at a time of environmental upheaval.

“During the era this site dates back to, the Middle Miocene, Earth’s temperature plummeted,” Djokic said. “If we can find more sites like it, it will help us decipher the way life on Earth responded to a rapid temperature shift; something that is increasingly relevant now because of climate change.”

Similar rusty red rocks are common in Australia, and in many other places around the world, too. Exploring more of them to find additional fossil sites could provide valuable insights into Earth’s history and unlock the secrets of bygone ecosystems, especially if scientists can construct a more detailed timeline.

“There was a wave of extinctions as a result of the climate changes in the Middle Miocene,” Frese said. “We’d like to know more about what happened before and after to piece together a more complete understanding of the evolution of life on Earth. How did plants and animals respond? Which species adapted successfully? Which died out? Are there any lessons we can learn to ease climate-related disruptions today?”

The Enduring Allure of the Past

Far more clues to Earth’s ancient past remain etched in the rocks scattered around the globe. Now, researchers have a human-validated data set that they could potentially use to train Artificial Intelligence (AI) to comb through enormous image sets in search of microfossils far more efficiently than humans could.

“That wasn’t the point of the citizen science project we led; we wanted to engage with the public,” Djokic said. “But perhaps a cooperative dynamic will emerge with citizen scientists helping to train AI to find fossils at different sites. They would remain an important part of the process because we need people who are more flexible in thinking than AI.”

And paleontologists are far from done with McGraths Flat. Ongoing analyses are helping scientists decipher additional mysteries preserved within the rocks.

The farmer’s simple act of moving rocks has transformed his field into a gateway to an ancient world that’s brimming with untold details about our planet and its inhabitants. Researchers at this site have uncovered fossilized flowers, spiders, fish, and even a bird feather, often preserved with such exquisite detail that they can see individual cells and smaller structures.

If all of this lay hidden in a remote corner of rural Australia, where the rhythm of nature intertwines with the pulse of human existence, what else may be out there just waiting to be discovered?

This story about microfossils previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story and photos by Ashley Balzer Vigil.