Story and Photos by Bruce McKay

Best intentions can be very effective, especially if you can keep to your goals, but some places and experiences can really put one’s resolve to the test.

Thinking back about my time in Quartzite, Arizona, in January of 2019, I’m reminded of the conversation I had with myself about keeping my purchases to a minimum. The fact is, I have more rock than I can cut in this lifetime, and since I don’t know if I’m going to be reborn as a lapidarist and I don’t know how to get the rocks I have in this life into the next, purchasing more may not be the wisest decision. Add to that, not all the rocks I have are the best quality, so if I find better specimens and add a pound to my pile, the lesser quality sinks to the bottom and out of sight. Sometimes it’s all about justifications as you wander the booths at the Quartzite Pow WoW.

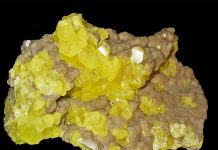

My rockhound logic softened the iron resolve not to purchase more rocks and allowed me to stop short in my tracks when I saw some of the most beautiful Variscite I have ever seen. There were huge slabs of lime green orbs mushed against each other into spiderweb patterns, and slabs cut from football-size chunks of material. A longtime fan of Variscite, I was smitten, looking at some of the finest I had ever seen.

The proprietor of the booth was Alan Chambers, partner with Rodney Frisby in the Vista Grande Mine outside of Mina, Nevada. We got to talking, and soon he invited me to come to visit the mine during summer. I slotted some time in early June and stopped by on the first leg of a cross country trip.

Making the Trek to Mina

Mina, Nevada is a town that I have driven through before and have no memory of, just a stretch of highway with a few buildings. Around 150 people still reside there, after the town dried up when the big mines closed. One of the nearby mines and once one of the largest silver producers in America, the Candelaria Mine, closed in 1990. Today, the space occupied by the mine since 1885, is now just a large pit with two ghost towns on its flanks. After the mine’s closure, one burger joint, one bar, a library that opens two days a week, and a Post Office is what remains of Mina’s downtown businesses. Upon reaching Alan Chamber’s mining compound on the outskirts of Mina, I was surprised by the amount of equipment. Huge graders, dump trucks, and drilling rigs were all over the place, looking like they had served many hours of mining duty. I thought this was a lot of equipment for mining variscite.

After an evening of great conversation, a delicious dinner, and a good night’s rest, Rodney, Alan, myself and two dogs took off for the mine in a pickup, hauling two all-terrain vehicles. Twenty miles down the highway, we turned down a gravel road and came to a stop in Columbus, Nevada. A ghost town left behind by a closed Borax mine, Columbus has just two buildings standing, but likely not for long. I think the next good snowpack could finish them off. On the way to the site, my guide miners pointed out various gold mines, turquoise mines, copper mines, mines everywhere. From downtown Columbus, my guides pointed to a mountainside nearby, indicating it was our destination, the Vista Grande Mine. Upon viewing the destination from afar, I saw a hillside formed from a bunch of brown rocks and not much else.

The area we were in, the Candelaria Mountains, has long been a prolific mining area, with miners recovering silver, gold, copper, iron, aluminum, tungsten, lead, borax, uranium, thorium, graphite, and mica, among others. As for the variscite and turquoise, which have been mined in this location since 1908, it occurs as veinlets along joints and fissures in limestone and shale. Variscite is a hydrated aluminum phosphate mineral colored by trace amounts of chromium. It is a cousin to turquoise, which is a hydrous copper-aluminum hydroxyl phosphate mineral colored by copper oxides. Once the lowly cousin to turquoise, variscite is now highly prized, and prices are climbing. In Dana’s Textbook of Mineralogy, it states, when found on islands and caves, variscite forms from phosphate provided by the decomposition of guano. I have licked Nevada variscite, and sincerely hope it did not come from a cave or island.

Prospecting Practices and Principles

In Columbus, we unloaded the ATV’s from the trailer and packed our gear into the storage boxes mounted fore and aft on each machine. Rodney grabbed one dog, Brownie, to be his passenger. Alan and I had the other pup, my standard poodle Wally, situated between us. We proceeded five miles, up across flats, heading uphill until we reached the backbone of a steep ridge, which drops off to both sides. Gouges on one side indicates where Alan once slid off the ridge while operating his backhoe, barely making it back up to the trail. That is where Alan told Wally and me to lean forward so we wouldn’t flip backward on the ATV.

Ultimately, we hopped off the ATVs about 100 yards from the Vista Grande Mine, and walked the rest of the way, making it to our destination safely.

Alan and Rodney love to prospect, and discovered this mine while explicitly looking for variscite. After depleting a nearby variscite mine, they were looking in similar geological rocks, wandering the hillsides, keeping an eye out for color: chips or veins of material. Alan spotted an old claim corner post with a band-aid box attached and figured he would check out what they had been digging.

Before digging into any area, Alan visits the Bureau of Land Management (BLM)

website to confirm the location of all legal claims in an area he and Rodney are prospecting. Then with a GPS unit in hand, the two miners know which land is open for exploration, claiming, and mining. If you are new to prospecting and digging, always be sure you know where the legal claims are, because a post in the ground with a note stating the area is someone’s claim doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a legal claim. For the claim to be legal, it has to be on file with the BLM, up to date information, and all yearly fees must be paid.

Near the old prospector’s corner post was a small exploratory cut dug into the hillside. The walls of the trench had a visible variscite vein in it, and Alan knew they were in the right location. The earlier prospector had probably been looking for turquoise, and when he only found the lowly variscite, he moved on. Alan called for Rodney, who began digging lower on the hillside, ultimately identifying the claim area they are now excavating.

Economic and Exploratory Mining

Some beautiful material has come out of the claim with the use of jackhammers and shovels. Still, the two knew they needed to move more of the mountain to mine economically, so they took an excavator up the steep ridge, and that is when they pulled out some of the football-sized chunks of gem variscite. With the excavator, they also dug a flat area to park the ATV’s and work the face of the hill. As I stood on the flat area looking around, I realized I was standing where those big pieces were brought to the surface, and I was ready to find one for myself!

Since I didn’t want to stand around while they worked, I became the water boy. As Rodney jackhammered, Alan shoveled the loosened rocks, and I sprayed water on anything that looked promising. When mining variscite, you must rinse off the rocks as you mine, or you may miss some good, dust-covered material and throw it into the mine dump. Alan and Rodney, like many miners, regularly look through their dump and they always find good pieces they missed earlier.

While we worked, an evening rain cleaned the face of the cut within the claim, revealing 15mm thick veins of variscite with black spiderwebbing. It looked just like the variscite that captured my heart back in the 1970s. We brought the jackhammer down, and Rodney carefully hammered around the veins to avoid pulverizing it. Unfortunately, with a jackhammer, sometimes you know you have hit the good stuff when good looking powder comes out of the hammer hole. Soon, we were pulling out some very nice material, and after we cleaned up all the visible variscite, we packed up and went home. As soon as they return to the mine compound, Rodney and Alan begin to cut the gems mined that day. Rodney uses a saw with thin blades to reduce waste and slabs everything, and then the two put the treasures into a pile they divide equally. While Rodney sells his through Facebook and Instagram as slabs, Alan cabs some and makes jewelry, along with selling some cabochons and slabs.

Alan then invited me to see some of his other mines, a turquoise mine he has with Rodney and gold mines he has himself. Every day I was able to go out and explore Mineral County as I had never expected. The county is around 4,500 feet elevation with mountain ranges rising above alluvial plains. The first mine we went to was a turquoise mine a few miles south of Mina, the Tower Mine. We crossed the alluvial plains and drove up to a rocky outcrop. I had seen some beautiful Turquoise from this mine, and I was ready to find a thick vein. We began to dig for turquoise while the dogs dug for prairie dogs. Our dogs had better luck, but we did find some nice quality good color rough that could yield two or three 2mm cabs.

Next on the list was a visit to Alan’s gold claim, the Red King Mine. Alan looks for free gold, which is gold that can be separated with a sluice box type operation. Alan is building a milling facility where gold can be recovered from the crushed rock out of his mines. The large mine companies use cyanide in huge heap leach piles to recover gold, but Alan is not interested in that type of mining. As we arrived at the mine, I saw yet again, a hillside of a bunch of reddish-brown rocks that were not indicative of anything important, in my estimation. However, Alan assured me that we could get a bucket of soil here and pan gold from it.

The next day we head to the Dinner Pail Mine. This gold mine dates back to the

1800s, and broken purple glass, old tin cans with lead dot seals, old horseshoes, and lots of fun garbage litter the hillside. Alan told me this mine got its name because there was so much gold that any hungry miner could go up there and get enough gold to buy dinner. We took pails full of dirt from the Dinner Pail mine and also the Red King mine to pan when we returned to the mining compound. Alan tried to show me how to pan correctly, but I struggled. I worried that I was tossing out gold with the swishes of the pan, but when I got to the bottom, sure enough, there was gold there! Tiny little specks but visible to the naked eye, from the panning of both locations.

As I left Mineral County and continued my trip, I left behind a beautiful country, wherein, apparently, everywhere you shovel a bucket of dirt, you get gold. Plus, if you know where to look, you can find some of the best variscite I have ever seen.

It is a place where I certainly can see beauty, but it seems I don’t quite have the miner’s eye needed to see where the treasures hide.