What are concho pearls? These beautiful, natural, freshwater pearls are found inside opalescent Tampico mussel shells at the bottom of rivers and lakes near San Angelo, Texas.

Against the backdrop of the windswept plains of West Texas—where thousands of cows and sheep roam freely, where incessantly running oil rigs and windmills dot the landscape, and thousands of acres of flat farmland give way to the Hill Country and to fertile valleys and rivers—nature creates something extraordinary: pearls.

The Appeal of Concho Pearls

If the term “freshwater pearls” brings visions of the cheap cultured pearls from China that are sold at gem shows, you must recalibrate your thoughts. These are extremely rare and extremely expensive, natural freshwater pearls.

The warm, glowing colors of the Concho pearls range from soft pink to lavender to purple. Most of them are small and rounded, while others come in irregular shapes. The round ones are the rarest, especially those that are 6 mm or more in diameter, which is considered large. Thousands of pearls were harvested in the 1960s through 1980s, but because of over-harvesting and drought, today they are true rarities.

What are Concho Pearls?

San Angelo is a city with a little more than 100,000 residents and is the Tom Green County seat. San Angelo is located in Concho Valley, at the confluence of three rivers: the North Concho, the Middle Concho, and the South Concho. The convergence creates the Concho River, which becomes a tributary of the Colorado River farther east.

The Spanish word concho, or concha, means “shell.” In the 17th century, Spanish explorers named the Concho River (River of Shells) because of its abundance of freshwater mussel shells. They considered the pearls a treasure and sent several expeditions to the area. It was found, however, that the yield of quality pearls—approximately one in 100 shells—was not profitable.

How Pearls are Formed

Pearls are organic gems that are found inside saltwater or freshwater mollusk shells. Pearls begin to form when an irritant, like a grain of sand, enters the mollusk. Over time, the grain becomes covered with nanometer-thin, crystalline layers of calcium carbonate, called nacre, which is secreted by the animal. The longer the shell stays in the water, the more layers of nacre cover the pearls. The thicker the nacre layer is, the better the luster of the pearl.

In ancient times, natural pearls were the only ones available. In nature, however, this only happens in one in about 10,000 shells, according to the American Gem Trade Association.

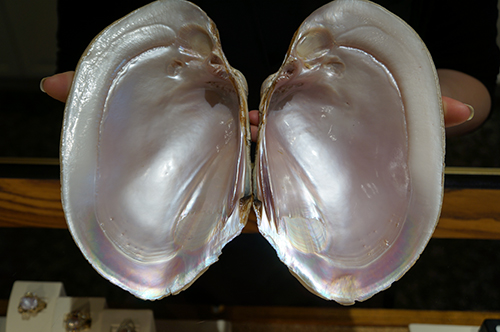

Tampico Mussel Shells

The natural Concho pearls are mostly found inside the shell of the Tampico pearly mussel (Cyrtonaias tampicoensis). These are freshwater bivalve (two-shelled) mollusks belonging to the family Unionidae, and they commonly burrow in the sandy or muddy bottoms of streams and lakes. At least 12 varieties of these shells inhabit the Concho rivers and surrounding lakes. Those who collect them have to dive 20 to 40 feet into murky, often snake-infested water during the hot summer months, or walk in three to four feet of water, feel for the shells with their feet, roll them left and right, and then pick them up. Not an easy job!

Pearl production has dropped dramatically during recent decades because of drought, poor quality of water due to pollution, chemicals and siltation, reduced water levels due to river dams and irrigation, and excessive overharvesting. Compared to 2,000 or 3,000 pearls recovered annually in the 1970s and 1980s, fewer than 300 pearls are now being found per year.

A Drop In Pearl Production

“The poorer the quality of water, the better the quality of the pearls”, and that “the deeper the water the shells are found in, the lighter the colors of the pearls; in the shallower water, the colors of the pearls are deeper,” says Mark Priest, of Legend Jewelers.

The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department saw an increase in diving permits with 500 permits issued in 1980. Thousands of pearls were harvested and hoarded for later use. Many of the jewelry stores rely now on that old stockpile.

Today, there are only seven permit holders in the state of Texas, with a moratorium on new licenses for the Texas commercial freshwater mussel fishery. Only handpicking is allowed—no dredges or brails. The mussel shell population is closely monitored by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

What are Concho Pearls? – A Harvesting History

Priest pointed out the dangers presented by the presence of venomous water moccasins and snapping turtles in the waters of the surrounding rivers and lakes of San Angelo. These hazards should deter any amateur, recreational or illegal divers. Also, diving in murky waters, with boaters possibly speeding over their heads, can be hazardous.

It is strictly illegal to go pearl-hounding in the water. Collect these natural gems only at the San Angelo jewelry stores!

In the late 1970s, a Tennessee shell company was harvesting hundreds of tons of shells, which were eventually sent to Japan for its cultured pearl industry. Shell divers were paid only for the shells but were allowed to collect the pearls for their own profit. Five large American companies bought millions of shells for 20 cents per pound and sold them to Japan for about $1 per pound.

Around the beginning of the 20th century, the Japanese discovered how to cultivate pearls, by skillfully inserting a small piece of mother-of-pearl cut into a bead or a piece of the mantle tissue into the mollusk shell. That begins the cultured pearl formation. In 1912, Japan became interested in the North American shells.

Most of the Tampico pearly mussels around San Angelo were found in Lake Nasworthy, just a few miles south of the city, and at O.C. Fisher Lake. Both are the result of dams on the Concho rivers. The Concho riverbed is rich in limestone, which formed from the accumulated shells of ancient mussels over the millennia.

What are Concho Pearls? – Size and Shape

Less than 10% of the shells have pearls inside them, and many of the pearls have imperfections or are attached to the shell. Pearl shapes are described as round, baroque, wing, petal, “turtleback” and “biscuit.” The majority of Concho pearls are tiny and almost worthless. Many pearls are spherical on the top and have a flat bottom, similar to mabé pearls; the latter, however, are pearls attached to the host shell that is cut off with a piece of the shell on the bottom.

The average size of Concho pearls is under 3 mm. One in a thousand may bring a high gem value. Concho pearls over 6 mm in diameter are considered extremely rare, and pearls over 10 mm may be worth thousands of dollars. We were fortunate to see some of these wonders in San Angelo.

Pearls take the same color as the mother-of-pearl that lines the inside of the shell. Concho pearls vary in color from yellowish-brown and peach to more common lavender, pink and purple hues. Soft pink is the most common color. The most highly valued are the intense-purple pearls, as well as some rare green and silvery-green.

Grading Concho Pearls

Concho pearls are graded in a similar way as other natural or freshwater pearls. The pearl’s luster and orient (the reflection of light through the multiple layers of nacre), color, size and shape are the main criteria.

Rounds are most highly valued, but some irregular pearls—especially if they display a figure or wing shape than can be incorporated into unique jewelry—may be sought after.

Although surface quality is a value factor, ring growths and blemishes on the Concho pearls are acceptable and may make the pearl of greater interest. The Concho pearls are uniform throughout and are therefore more durable compared to cultured pearls that only have a thin layer of nacre over a bead.

Lapidaries also cut the iridescent mother-of-pearl into freeform pieces and set them into jewelry. Please remember that when you cut any type of shell, you should wear a dust mask and run the machines with a lot of water in order to avoid inhaling any toxic dust.

Legend Jewelers advises customers to care for their Concho pearls the same way they would care for any other pearls: Keep them free of dirt, hand lotions, perfumes, cosmetics and perspiration, store them away separately, and keep them away from pool chemicals.

Storied Pearl Culturing

A 20th-century renaissance in cultured pearls began in 1968 when prominent businessman-turned-goldsmith Bart W. Mann and business partner Jack A. Morgan spent six months fishing for pearls in a lake north of San Angelo. Even though pearls occurred in only about one out of eight shells, by the time they finished their hunt, they had accumulated a staggering 6,000 pearls! According to Priest, Bart Mann Originals assembled the only strand of matched, perfectly round pearls in the early 1980s, after 17 years of collecting.

Mann taught himself how to cast gold in the late 1950s. He experimented with casting flowers and lizards, then started creating beautiful jewelry featuring the Concho pearls. Much of his jewelry featured the images of sea life, like starfish, seahorses and shells, and was set with one or more Concho pearls. He later created some very complex, detailed sculptural gem scenes, and goblets and chalices inspired by natural forms and the Renaissance Italian master goldsmith Benvenutto Cellini. Mann incorporated American gemstones and high-grade sapphires, as well as Concho pearls, into all of his artwork.

In 1969, Mann and Morgan opened a jewelry store in downtown San Angelo, Bart Mann Originals, and sold Mann’s unique jewelry.

A GIA graduate gemologist, Priest joined Morgan in 1975. In 1995, he left Morgan and opened Legend Jewelers, which is currently located in San Angelo’s downtown area, near the Concho River.

Mann passed away in 1974, and some of his masterpieces have been donated to the Fine Arts Museum in San Angelo. Some of these, including some incredible goblets, are pictured in the book Imagination in Gold (1965).

This story about what are concho pearls previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe! Story and Photos by Helen Serras-Herman