By Becky Solon

Those of us with artistic inclinations appreciate the natural sculptures of Mother Nature. As a jeweler and a lapidary artist, I have been using rock-tumbling techniques for several years in an effort to produce gemstones that preserve the natural features of chalcedony agate specimens.

It all started when I realized that it would take endless hours in front of my grinding wheels to remove weathered surfaces that had accumulated over eons of Earth’s history. The mechanical similarity of active rock tumbling to the slow cycles of water erosion made it clear that I could save myself a lot of effort, while duplicating nature’s work at an accelerated rate.

Exploring Tumble-Finishing Techniques

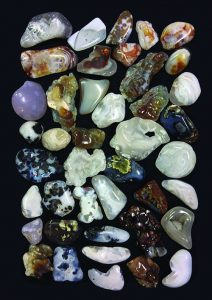

I soon found it helpful to take advantage of the benefits of rock tumbling to open windows into a concealed universe of nature’s agate master forms. Tumble-finishing techniques allowed me to determine the worthiness of my rough material for cabochons cutting. I have used this procedure to determine the best cross-sectional views for my cab-making projects. While involved in this process, I discovered the intricacy of these gemstones and wanted to conserve much more of the natural sculpture that was produced by the processes of gem and mineral formation. I also wanted to reveal the characteristics that made each specimen unique.

Since retiring to the awesome state of Arizona nine years ago, I’ve fulfilled my dream of joining a rock and gem club. The experience of rock collecting with a knowledgeable group reinforced my passion for preserving agates in their myriad natural forms. I purchased Riker display trays to organize my collection and carry specimens to meetings for show-and-tell discussions.

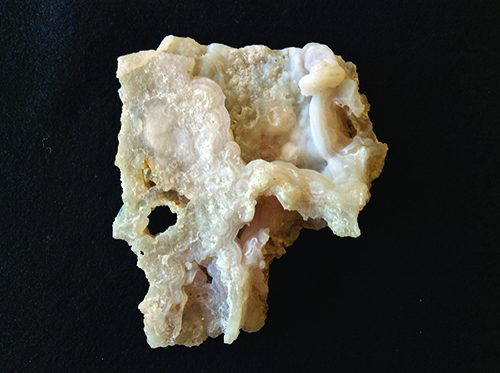

After participating in a number of club-sponsored field trips, I developed an interest in collecting chalcedony roses and rosettes and became increasingly fascinated with the complexity of their colors and formations. I started a specialty collection to showcase my finds. On frequent occasions, weathering had eroded intricate specimens out of their volcanic host rocks. Despite the quantity of collectible specimens, I did not hesitate to look for broken pieces that had their own potential use in small, cameo-size designs.

Trading for Chalcedony

A few years ago, I participated in a gem and mineral show and traded an Ajo, Arizona, copper mine specimen for a collection of chalcedony roses. Three years later, two retired club members gave me their chalcedony collections because they knew I had a passionate interest in studying the specimens. The translucent quality of many of the white, orange, pink and blue specimens and inclusions appealed to my cab-carving and gemstone-making mania. I keep my own collection of cabs for jewelry settings, but I continue to experiment with rock-tumbling procedures for my agate specimens, whose shapes and subtleties dictate special scrutiny and consideration.

Chalcedony is a semiprecious silica (aka silicon dioxide, SiO2) gem material in which the mineral occurs in several different crystal forms. These crystals are tightly intergrown and so small they cannot be seen without a microscope, a structure that is called “microcrystalline” or “cryptocrystalline”. The various colors in chalcedony are caused by mineral impurities.

Chalcedony’s surface appearance can be botryoidal or mammillary. It can occur in massive, stalactitic and nodular forms, fill amygdules, or form an outer layer around the crystalline centers of geodes.

Varieties of chalcedony include aventurine, carnelian, chrysoprase, heliotrope (bloodstone), and onyx. The term “agate” is reserved for chalcedony that exhibits distinct, multicolor banding. The fine distinctions among these varieties can be explored in detail in a mineral reference book.

New Horizons Inspire New Interests

Over these past few years of retirement in the rockhound haven of Arizona, my collection has more than quadrupled in size and now includes some self-collected specimens of colorful varieties of chalcedony agate. This exposure to new horizons led to my interest in fire agate. Its formation in cracks and openings caused by gas bubbles in solidifying lava gives the rough pieces a bubbly or botryoidal surface. These agates exhibit rainbow patterns of iridescent color that is caused by light diffraction. I studied the color effects of polished pieces with a hand-held microscope and saw what appeared to be tiny panoramas that expanded into canyon vistas.

Other botryoidal, dendritic and druzy curiosities caught my attention at a local agate prospecting site, all of which were too tempting to resist! I was glad that I took advantage of the opportunity, even though I had to hike uphill on steep rocky slopes for over a mile.

The work of collecting and inspecting field rocks, while hard, is often rewarding. Sorting is

an essential procedure of the often time-consuming activities of rock prospecting and processing, but if done correctly, it can save time and money, while going a long way toward ensuring successful mineral collecting results. Acquiring the good habit of carefully selecting worthy specimens in productive geological formations will save work and aggravation in the long run. Over collecting is a common habit among zealous rockhounds, and can lead to an accumulated pile that is too easily relegated to the yard as landscape décor.

When I’m focused on getting to the bottom of my mystery mounds, I routinely sort my specimens into one group to be tumble processed and another group to be preserved “as found”. Then I clean them all with a toothbrush and water gun to reveal hidden details. This step requires a considerable amount of patient work, repeated power washing, and close inspection to clean out the deepest whorls, crevices and cavities. It’s extremely important to eliminate undeserving specimens that should have been abandoned in situ as “leaverites”. So, of course, careful on-site inspection is a must to avoid overloading myself, the car, and the yard! And I try to avoid critical overtures from my spouse who knows “what’s best for me”!

Transforming Stones

There are always plenty of interesting rocks to analyze for special treatment. I discovered that I could transform intriguing specimens into viewing stones simply by grinding rough edges flat to form stable bases for unique tabletop displays. Using my imagination, I’ve created some interesting shaggy-dog sculptures using this procedure. My collection of naturally occurring stalactitic and stalagmitic minerals inspired these ideas and gave me more reasons to enjoy my rock-collecting obsession.

Above all, rock tumbling is especially useful for processing rock fragments that would otherwise be discarded or considered unattractive for other lapidary treatments. Tumble polishing can unveil the unseen drama of undulating gem colors and patterns. But one of the most important attributes to be preserved when tumbling chalcedony agates is the agate’s highly varied sculptural qualities, a complex and mysterious gem construction of great antiquity.

My lifelong interest in capturing the sculptural features of agates with a rotary-tumbling process was a result of another profound realization: that my efforts at rock carving, however painstaking, could never equal Mother Nature’s intricate formwork. My firm opinion is that the elegantly contoured convolutions of countless chalcedony remnants of past volcanic eras represent geochemical and weathering processes. For example, the exquisite contact points in the lava cavity’s matrix are artifacts of unparalleled beauty, above and beyond mere geofacts! The sculptural quality of every interior and exterior surface of these chalcedony artifacts is a feat of mineral formation and habit construction.

There are so many delicate details to admire and contemplate.

I consider myself to be a skillful lapidary artist and cab-making craftswoman, and regard this category of the lapidary arts to be a form of gem carving; however, I came to realize that brute strength is often needed for intricate and precise hard rock reduction. Even with the assistance of my Dremel diamond tools, such work loses its appeal when it involves physical tasks that are just too formidable and challenging for a practical, health-conscious woman like myself.

Refining Rotary Tumbling Processes

By comparison, my rotary tumbling procedures involve a highly engineered “perpetual motion” process that includes buffing, cleaning and polishing methods of my own derivation, using three barrel loads running simultaneously. The cardinal rule is that rocks of the same hardness should be run together in the same batch. I’ve discovered that the distinctive shapes of the respective chalcedony igneous materials maintain their integrity as long as the agates and other chalcedony minerals of the same hardness (approximately 7 on the Mohs Scale of Hardness).

Rocks that develop cracks should be set aside to be evaluated for possible work at the grinding wheel. If these rocks are intended for coarse tumbling in another starting batch, make sure that the damage is not extensive and that the agate is worth salvaging.

While cleaning rocks between grit changes, continue doing thorough inspections and removing the least desirable specimens. Periodic inspections at the halfway point of each grinding cycle help to ensure that rocks are not left in each grit size too long, altering their original sculptural characteristics.

Multiple cycles using my Lortone rotary rock tumblers have helped me develop consistent results for a uniform polish across the undulating topography that one encounters on many agate rock surfaces. The application of Arm & HammerTM 2X Concentrated Liquid Laundry Detergent, Clean Burst, is an essential step in my rock-tumbling operation. The discovery of this product was, in fact, a Eureka! moment. I’d found a solution to the problems involved in accomplishing effective rinsing, cleaning and burnishing/prepolishing phases after completing at least three grinding cycles at each silicon carbide grit size. (I’m using the term “burnishing” to mean a prepolishing phase.)

Drawing on Experimentation to Elevate Techniques

Years of experimentation with polishing compounds had proved much less reliable than the results achieved from the concentrated power of this detergent! I later learned that other liquid laundry detergents have proved effective for colleagues, who say that the chosen product just needs consistent application.

Many of Nature’s byproducts can be found relatively intact and undamaged, so I always collect well-preserved specimens. With the accumulated experience of over eight years of participating in field trips to agate-collecting areas, I look for sparkling crystal drusies, intricate, flowerlike surface features, nodular ovoids, tube-infused shapes, and bubble-embossed surfaces of botryoidal silica. Identifying the best collectible specimens is always the first step. Less interesting fragments can be set aside for tumble processing with a piecemeal batch as a second step at home.

I have experimented with other chalcedony specimens whose geometries are too complex to submit them to any more than a single fine-grit tumbling cycle. In these cases, I have used additional rinse cycles with my liquid detergent to polish near-perfect pieces for up to five days, sometimes running the same stones through successive iterations for optimal results. Using this procedure, I discovered that I could create some interesting etched-surface effects on my gemstones.

I could not succeed at this arduous and ambitious task without the assistance of my husband, Tom, in the painstaking work of cleaning out barrel loads of heavy rock sludge, which must be collected into plastic containers for safe disposal in trash bins. The process of draining the messy, mud-soaked stones into large colanders balanced atop 5-gallon buckets is a task he is accustomed to doing with good-natured generosity of his time. He has developed a keen eye for sorting promising specimens into graded batches.

Changing Fragments Into Usable Material

Lackluster fragments can be tumble ground to a smooth surface and evaluated for quality and continuing product improvement. There is hope here if you believe in reincarnation! If “junk” specimens are given the full treatment, and if periodic inspection indicates that these efforts will likely lead to praiseworthy results, these rocks may eventually be given a new life as gemstones.

In this article, I’ve chosen to discuss the sculptural potential of all specimens, whether they

are processed for 3-D polishing or preserved as field treasures. Although it’s true that the latter category represents an important portion of my mineral collection, I am equally proud of my tumbled gemstone collection. I’ve always recognized the value of transforming less-than-ideal field specimens into gemstones as a 3-D art form. Doing so achieves mineralogical preservation and can sometimes result in highly prized collectibles.

Thorough and exhaustive sorting of agate material is required while still working in the field, but the experience of collecting field specimens is just one of many adventures of discovery that extend to evaluating each agate for its intrinsic gemstone value. Because of the experience of viewing previously hidden features of specimens, I feel that I learn even more about mineralogy when I’ve completed a number of tumble-polished gemstones.

The challenge in my lapidary and jewelry work has been to utilize the best results of my tumble-polished stones for several types of jewelry elements: 1) stunning one-of-a-kind beads that I’ve created by drilling polished chalcedony roses and other field trip and beachcombing finds; 2) individual focal pendant pieces that can be framed in wire work, sheet metal, beads, or other media and worn as natural semipolished or highly polished agate sculptures; 3) multiple freeform pendant elements that are designed to be detachable interchangeable components using precious metal findings arranged in a combination of mirror-finished agate varieties that exhibit a range of colors; and 4) special, intact field specimens that include thin, druzy sprays and encrustations that may just need minimal refinement with my Dremel flexible shaft diamond bits or my Barranca diamond combination unit.

As a specialty category of mineral field finds, these collectibles make a separate “jewelry-grade” source of focal pieces for any number of settings and ingenious applications of metallic coating and electroplating technology, as seen on the internet, in jewelry supply catalogs, and in gem and mineral shows. This specific technology will not be discussed in this article.

Unique Views of Agate Offerings

A fifth category of my agate sculptures that can be enjoyed as miniature collectible showpieces and exhibits encompasses the viewing stones that I’ve enjoyed producing at smaller scales than those typically found on the internet. These curiosities have given me another outlet for enhancing complex agate formations, as previously discussed with regard to crafting chalcedony “carvings”. I like to think that my work on shaggy-dog displays can earn positive reactions.

My overall objective is to capture the gemstone concept by mastering the best possible tumble-finishing procedures and then enhancing the various features of these stones in my jewelry projects. My challenge is to find the best jewelry-making techniques that take advantage of the natural-looking sculptures produced by tumble polishing. I also strive to make settings for intact specimens that I want to preserve and display as wearable exhibits of nature’s creations.

Prior to retirement, I completed small, custom jewelry projects that entailed special cab work for colleagues and for my own use. Now, as a retiree with time to pursue my passions, I’ve combined my interests in metallurgy, mineralogy, and jewelry design to carve out a new career that is as fun as it is an educational adventure. Attending jewelry-making classes at a nearby college, I’m learning as much as possible about the techniques available to me as a metal worker. I’ve made jewelry pieces using sheet metal and wire in various gauges, and made use of my many handmade cabs.

I have also applied these new and improved skills to colorful geode nodules, chalcedony-infused fossil wood, petrified sponge, and agatized coral. I have a growing hoard of specimens that I like to combine with botryioidal chalcedony and other intriguing desert stones in my designs. Whether enjoyed as wearable or viewable sculptural art, these products of a lifelong hobby appeal to me because I appreciate the mysterious attributes of their genesis and evolution.

For several years now, I have been striving to combine my passion for showcasing the best products of my rock cutting, processing and polishing efforts. My experience affirms that chalcedony agates are best appreciated for their natural formations and attributes, which heighten my awareness of our planet’s natural history. Above all, the study of chalcedony agate mineralogy, an interest that is shared the world over by millions of hobbyists, has reinforced my desire for academic and artistic fulfillment.