Non-zeolite minerals offer striking beauty and scientific intrigue in volcanic mineral collecting. Found in the same cavities and geologic settings, these minerals—like cavansite, apophyllite, prehnite, datolite, and pectolite—form vibrant clusters, gemmy nodules, and delicate coatings that captivate collectors. From the brilliant blues of Indian cavansite to the pastel greens of New Jersey prehnite, non-zeolite minerals bring variety and rarity to any collection.

Larimar: A Gem-Quality Form of the Non-Zeolite Mineral Pectolite

The gem world easily recognizes the lovely blue-and-white stone known as larimar—a relatively recent discovery in the realm of colored gemstones. This striking gem owes its soft blue color to trace amounts of copper ions. But larimar has a few surprises tied to its history and mineral identity.

One lesser-known detail is that larimar was rediscovered in 1974 by Miguel Méndez and Peace Corps volunteer Norm Rilling, who spotted ocean-tumbled pebbles in the surf along a Dominican Republic beach. However, the mineral was actually first found in the Dominican mountains in 1916 by Father Miguel Domingo Fuertes Loren. He applied for a mining permit to extract the blue stone, but the government denied his request, and the discovery faded from memory until its reappearance decades later. Rilling chose the name “larimar” by combining his daughter Larissa’s name with “mar,” the Spanish word for sea.

So why include a beautiful blue gemstone in an article on non-zeolite minerals? Larimar is actually a gem-quality variety of pectolite—a non-zeolite mineral commonly found in volcanic cavities alongside zeolites. In its more typical form, pectolite doesn’t resemble larimar at all. Instead, it appears as radiating fans of long, brittle, needle-like crystals that can reach several inches in length.

Pectolite’s normal crystal form of hard, needle-thin, very brittle, sharp, acicular crystals have an affinity to break off when they penetrate the skin. Without leather gloves, a collector will carry traces of these penetrating needles as a myriad of slivers. Pectolite is common in the New Jersey deposits in its acicular radiating crystal form, but is almost unknown in the very prolific and popular zeolite sources in India and the Northwest.

Cavansite: A Brilliant Blue Non-Zeolite Mineral from India and Oregon

Larimar isn’t the only non-zeolite mineral to make a recent splash in the minerals for collectors market. Another standout is the vivid blue mineral cavansite, which first appeared in Oregon at the Owyhee Dam site in Lake Owyhee State Park, Malheur County, and near Goble in Columbia County during the 1960s. Though discovered in 1961 by two rockhounds, cavansite wasn’t officially recognized as a new mineral until 1967.

Despite the presence of attractive crystals in Oregon, cavansite didn’t attract much attention until a major discovery in 1989 in India changed everything. Found in the Deccan Plateau’s volcanic rock at several quarries in the Wagholi complex and in the Lonavala quarry in Maharashtra, Indian cavansite quickly became a collector’s favorite. What made this find so exciting was not just the mineral’s rich blue color—deeper and more saturated than Oregon’s paler crystals—but also the sheer number of specimens unearthed.

Cavansite from India typically appears as radiating, deep-blue spherules up to an inch across, often displayed beautifully against white stilbite or apophyllite. These mineral associations created a stunning visual contrast and contributed to the gem’s popularity at the 1989 Tucson Gem and Mineral Show, where it was met with immediate enthusiasm. Dealers quickly sold out, and cavansite secured its place as one of the most desirable non-zeolite minerals on the market.

Though individual cavansite crystals are rare, they are orthorhombic and appear as slender, often wedge-shaped blades. The crystals usually form tight, radiating clusters rather than freestanding individuals. Occasionally, these clusters take on unusual worm-like shapes, adding to the mineral’s visual intrigue and collector appeal.

Apophyllite Becomes a Group Name, Not a Single Mineral

Apophyllite is another example of a mineral whose name has evolved significantly over time. Once considered a single mineral species, apophyllite is now recognized as a mineral group, thanks to its complex chemical variability. Early mineralogists referred to it simply as apophyllite, despite its intricate composition. Today, we understand that various metal ions can influence the chemistry of the mineral, leading to the classification of multiple distinct types.

Chemically, apophyllite is a mouthful—composed of potassium, calcium, silicate, fluoride, hydroxide, and water. The proportions of these constituents vary, which prompted scientists to refine the mineral’s classification. Using the dominant element as the distinguishing factor, three primary species were defined: natro-apophyllite (NaF), fluorapophyllite (KF), and hydroxyapophyllite (NaOH). This naming convention was accepted by the International Nomenclature Commission to provide clarity in the increasingly detailed world of mineral classification.

Apophyllite: Common Non-Zeolite Minerals in Volcanic Cavities

Parent Géry, Wikimedia Commons

Among minerals found in volcanic cavities, apophyllite is one of the most common non-zeolite minerals, second only to quartz and calcite. Its crystals typically form in the tetragonal system, resulting in a square cross-section that gives many crystals a cube-like appearance with modified corners. These more common varieties are often colorless to white, lacking the vivid hues collectors tend to prize.

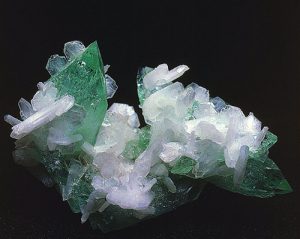

However, another highly sought-after form of apophyllite features green prismatic, pyramidal crystals, often doubly terminated and arranged in diverging clusters. These vibrant crystals owe their color to trace amounts of vanadium and can range from a delicate pale green to a rich, darker shade. The Deccan Traps of India are especially famous for producing this form, with quarries regularly yielding spectacular specimens.

Green Apophyllite and the Stunning Indian and U.S. Finds

Indian quarries have delivered some of the most dazzling green apophyllite crystals available to collectors. These specimens often feature diverging crystal clusters several inches across, with individual crystals sometimes exceeding an inch in length. Particularly eye-catching are the long, chain-like formations that wind across matrix surfaces—showy pieces that are instantly recognizable and highly prized.

Yet despite the popularity of Indian apophyllite, one of the most thrilling discoveries came from the United States. In the mid-1970s, quarry operations in Centerville, Fairfax County, Virginia, uncovered a wide seam filled with pale green prehnite. Growing on that prehnite were breathtaking apophyllite rosettes—perfectly formed tabular crystals up to four inches across. These sharp-edged clusters quickly captured the mineral world’s attention. Many were collected by volunteer rockhounds, and some of the finest specimens—including a standout piece—now reside in the Smithsonian Institution.

Prehnite: A Common Non-Zeolite Often Mistaken as a Zeolite

Of all the non-zeolite minerals, prehnite is certainly the mineral most often thought to be a zeolite because it is so common. It is found in ore veins and even sedimentary situations but is best known as a colorful companion to zeolites, which led to the misunderstanding.

Prehnite has an easily recognized form, as it is most often found as a green crystallized coating on matrix specimens. The mineral is orthorhombic, but most often forms as botryoidal crusts on matrix, suggesting it forms fairly early during crystal deposition. As such, it often hosts other minerals that form later. It is also commonly seen lining the walls of open vugs. The surface of prehnite is often very sparkly due to tiny crystal terminations.

In this country, prehnite is very common in New Jersey quarries like New Street and Prospect Park. It has also been found in quantities in New England. The most unusual types are pseudomorphs after anhydrite that look like fingers or in arrowhead shapes. Crystals of prehnite are also found with copper in the Keweenaw copper deposits.

Gem-Quality Datolite Nodules from Michigan

Another non-zeolite that shows up in the Keweenaw, Michigan deposits is datolite, but not in the glassy light green crystals found in ore deposits and trap quarries. The Michigan datolite is found as very lovely porcelain-like nodules that can be cut and polished. When cut, these nodules often have a very attractive interior ranging from stark white to brilliantly colorful due to impurities that can make them a very colorful green, yellow-orange, or even classic copper-colored or with delicate copper wires jutting into the interior. The most unusual nodules are the classics with small crystalline copper bits throughout the white porcelain mass. The contrast between reddish copper and white datolite is very attractive.

Crystallized datolite is found with zeolites as small, multi-faced glassy crystals in tight clusters on matrix. The largest datolite crystals measure up to two inches and came from the Lane quarry in Westfield, Mass. Most collectors have specimens from the New Jersey sites, including from a road cut at Fort Lee dug to connect to the George Washington Bridge. A similar road cut happened when Interstate 80 was cut into the Watchung Mountains in New Jersey.

Check out a close-up view of non-zeolite finds at the Roncari Quarry…

In the last couple of decades, we have been most fortunate as large, pale green datolite crystals in quantity have come from two working ore deposits, Charcas, San Luis Potosi, Mexico, and Daln’egorsk, Siberia. The Siberian crystals rank among the best and largest datolites ever found.

Non-Zeolite Minerals: Final Thoughts

With the steady flow of both zeolites and non-zeolite minerals—especially from the rich volcanic quarries of India—collectors today have the opportunity to build a diverse and visually stunning suite of specimens. From vivid cavansite to shimmering apophyllite and gemmy datolite, the variety and availability of these minerals show no signs of slowing. Whether you’re just starting out or expanding an advanced collection, non-zeolite minerals offer color, form, and scientific intrigue worthy of any display.

This article about non-zeolite minerals previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Story by Bob Jones. Click here to subscribe.