Baltic amber in northern Europe is known as “sunstone” and “solar stone” for its golden, sun-like glow. It is also known as “Baltic gold” for its huge economic impact — an impact represented by 60,000 tons mined during the region’s mining history, with half of that mined in the past 100 years.

Today, tens of thousands of people work in the regional amber industry. Amber is the area’s iconic souvenir, and museums that showcase amber are significant tourist attractions. With the recent emergence of Ukraine as a major source of amber, northern Europe’s amber output is soaring. Average grades of amber now sell for several hundred dollars per pound, and regional production is estimated at 1,000 tons per year—a historic high.

But there are two sides to amber mining in northern Europe. With few alternative employment opportunities and lured by record amber prices, some 20,000 Kaliningrad Russians and Ukrainians now work as independent amber miners. And virtually all are unlicensed and unregulated. While amber mining provides a living for thousands and has boosted production to record levels, it has also brought environmental devastation, economic chaos, corruption, violence, protection racketeering, black-marketeering, and rampant smuggling.

But there are two sides to amber mining in northern Europe. With few alternative employment opportunities and lured by record amber prices, some 20,000 Kaliningrad Russians and Ukrainians now work as independent amber miners. And virtually all are unlicensed and unregulated. While amber mining provides a living for thousands and has boosted production to record levels, it has also brought environmental devastation, economic chaos, corruption, violence, protection racketeering, black-marketeering, and rampant smuggling.

The complex origin of northern Europe’s amber rush is rooted in the geology, occurrence, and history of amber and the centuries-old reverence for amber. In recent years, regional economics and politics are among the drivers of the amber rush. Amber is a fossilized tree resin — a valid definition — if the meaning of the word “fossilized” is expanded. While most fossils are created through such physical processes as a mineral replacement and sedimentary impression, amber formation is an entirely different molecular polymerization process.

Baltic Amber – Fossilized Tree Resin

Due to the lack of a crystal structure and definite composition, amber is classified as an organic non-mineral, a natural substance of origin that is neither a mineral nor a mineraloid (a noncrystalline, mineral-like material). Chemically, amber is an oxygenated hydrocarbon with a variable composition that consists roughly of 80 percent carbon, 10 percent oxygen, 9 percent hydrogen, and traces of sulfur and phosphorus.

Amber originates as the resin that various tree species exude as a defense mechanism against fungal or insect attacks. Resins are complex hydrocarbons consisting of organic acids, sugars, esters, and terpenes, the latter being the key to the formation of amber.

Newly exuded, soft, sticky tree resin begins the long process of fossilization almost immediately when its most volatile terpenes begin to evaporate. Then the less-volatile terpenes slowly polymerize, linking together into long molecular chains to homogenize and harden the resin. Atmospheric oxygen prevents further fossilization, however, as the surface of the resin oxidizes, it cracks, and sloughs off as fine particles and the resin mass begin to disintegrate.

But to become amber, further change must occur within an anaerobic environment. In long-term burial conditions devoid of free oxygen, resin first turns into copal, a partially polymerized resin with an amber-like color and general appearance. Although sometimes sold as amber, copal is soft and chemically unstable. Chemically stable amber only develops when copal remains anaerobically buried for millions of years, resulting in the remaining terpenes eventually polymerizing completely.

Baltic Amber Properties

Amber is opaque to transparent with a resinous luster. Its colors are usually in the brown-gold-yellow-orange range; less common are white, red, green, blue, and black. Its Mohs hardness of only 2.0-2.5 makes it eminently workable. Amber’s relatively low refractive index of 1.539-1.545 roughly equals that of quartz. But unlike transparent gemstones, amber does not depend upon refraction (bending) of light for its eye-catching appearance, but rather upon the transmission and reflection of light.

Lack of density is one of amber’s most distinctive physical properties. With a specific gravity of 1.05-1.10, it is only a bit denser than freshwater (specific gravity of 1.0). Amber, therefore, sinks in freshwater but floats in salty water. One cubic inch of amber weighs only about a half-ounce (14 grams). Amber’s low density explains both its occurrence on Baltic beaches and the methods used to mine it.

properties. With a specific gravity of 1.05-1.10, it is only a bit denser than freshwater (specific gravity of 1.0). Amber, therefore, sinks in freshwater but floats in salty water. One cubic inch of amber weighs only about a half-ounce (14 grams). Amber’s low density explains both its occurrence on Baltic beaches and the methods used to mine it.

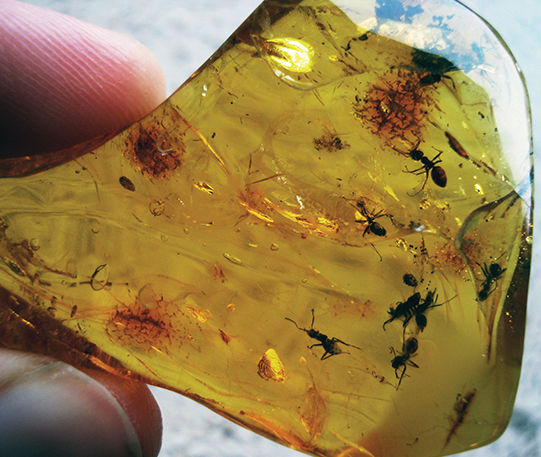

Amber is known for its inclusions of small plant and animal life forms. When exuded tree resin traps and covers these life forms, its hygroscopic sugars draw away water to desiccate and preserve these life forms in remarkable detail.

How Baltic Amber was Formed

Some 44 million years ago, in a much warmer Eocene Epoch climate at what is now the Baltic Sea, a dense conifer forest exuded large amounts of resin in conditions favorable to amber development. Much of this amber became concentrated in a 5-to-20-foot-thick, sedimentary layer of “blue earth.” Concentrations of glauconite minerals cause the layer’s distinctive, grayish-blue color. Glauconite minerals are a series of complex basic potassium aluminosilicates. On average, each cubic meter of blue earth contains four pounds of amber.

This amber-rich blue earth remained buried until the Pleistocene Epoch Ice Age glaciers scoured out the depression now occupied by the Baltic Sea. Some 15 million years ago, when sections of this layer became exposed on the sea bottom, amber washed from the sediments. Because of the Baltic Sea’s low salt content, this amber did not float, but “rolled” with the current along the sea bottom.

Large amounts of it ended up on the beaches of what are now Kaliningrad, Russia, and adjacent Poland and Lithuania. In late Paleolithic times, amber must have covered these beaches. Archaeological evidence indicates that as early as 13000 BCE, Baltic “beach amber” was being fashioned into simple ornaments, making it the first gem material to be collected and worked.

Baltic Amber – Evolution of Amber Mining

By 3500 BCE, Baltic amber was being widely traded and had already reached the Mediterranean region. Beads of Baltic amber appear within the 3,300-year-old funerary mask of the Egyptian ruler Tutankhamen. By Roman times, a network of trade routes called the “Amber Road” linked the Baltic Coast and Rome, with Baltic amber becoming a popular choice to trade for Roman silver, glass, and iron.

In 1308 CE, when most amber was being made into rosary beads and religious icons, the Teutonic Order, a German religious-military group, took control of the Baltic Coast, monopolizing the amber trade and establishing amber-craft guilds. By 1500, two new methods of amber collecting were in use: One was the use of nets to gather amber that had become attached to floating seaweed; the other involved inland digging into the blue-earth layer. By then, the Polish city of Gadask had become the center of the amber trade.

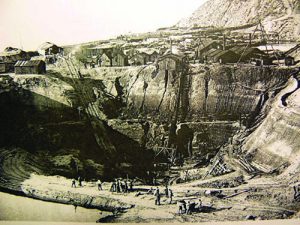

Systematic amber mining evolved in 1780 with the development of a 100-foot-deep open pit at Königsberg, Germany (now Kaliningrad, Russia). Large-scale, mechanical mining began in the 1870s. By 1926, Königsberg boasted a state-controlled amber-manufacturing facility, 2,000 people working in the amber industry, and a large open pit that produced 300 tons of amber per year. About 10 percent of this amber was used to make fine jewelry and decorative items. Another 30 percent, mostly medium-grade material, was heated and pressed into blocks for the manufacture of electrical insulators and other industrial products. The remaining low-grade amber served as fuel or was powdered and made into lacquers and enamels.

Systematic amber mining evolved in 1780 with the development of a 100-foot-deep open pit at Königsberg, Germany (now Kaliningrad, Russia). Large-scale, mechanical mining began in the 1870s. By 1926, Königsberg boasted a state-controlled amber-manufacturing facility, 2,000 people working in the amber industry, and a large open pit that produced 300 tons of amber per year. About 10 percent of this amber was used to make fine jewelry and decorative items. Another 30 percent, mostly medium-grade material, was heated and pressed into blocks for the manufacture of electrical insulators and other industrial products. The remaining low-grade amber served as fuel or was powdered and made into lacquers and enamels.

Amber mining halted during World War II, an era that also brought the demise of the fabled “Amber Room,” a showcase palace room made of amber. King Friedrich I of Prussia began creating the Amber Room in 1701 at the Charlottenburg Palace in Berlin, Germany. In 1716, it was disassembled and moved to Saint Petersburg, Russia, as a gift to Peter the Great, czar of the Russian Empire. When reassembled, the walls of the Amber Room contained six tons of fine, thinly sectioned amber, along with quantities of gold leaf and gems. During World War II, the invading German army moved the Amber Room from Saint Petersburg to Königsberg, Germany, where it disappeared amid the Allied bombing raids of 1945. Its fate remains a mystery.

Following the war, Königsberg became part of the Soviet Union and was renamed Kaliningrad. The Soviet Union then closely controlled the amber trade through its Kaliningrad Amber Combine, which operated the 200-foot-deep Primorsky open-pit mine, along with a sizeable amber-manufacturing facility. The open-pit, in which draglines exposed the blue-earth layer and high-pressure water jets freed the amber, yielded about 300 tons of amber per year. Because of omnipresent Soviet state surveillance and harsh penalties, the output of unlicensed amber mining was negligible.

The events that would radically alter amber mining in northern Europe began in 1991 with the collapse of the Soviet Union left Kaliningrad as a Russian enclave bordered by Poland and Lithuania’s independent nations. Although citizens of these former Soviet states enjoyed greater personal freedom, subsequent economic chaos created rampant unemployment, particularly in Kaliningrad.

Jurassic Appeal Drives Amber Interest

Then, in 1993, the blockbuster movie Jurassic Park, based on the premise of modern-day dinosaurs being cloned from amber-preserved DNA, focused worldwide attention on amber. Many people who previously knew little about amber now wanted to own some. Meanwhile, China had emerged as a significant economic power with a vast, new consumer class eager to acquire luxury items, including amber jewelry and carvings.

As Chinese buying drove amber prices upward in the 2000s, demand exceeded the Kaliningrad Amber Combine capacity. When a black market contingent began buying amber, thousands of Kaliningrad’s unemployed citizens became “black diggers” — independent, unlicensed miners. They collected amber on the beaches, dove for it in the Baltic Sea, or dug for it on land.

With black-market middlemen paying Euros and U.S. dollars, illegal mining boomed. But the business was beset with crime and violence, and both the police and freelance protection racketeers demanded bribes. Nevertheless, with hard work and a little luck, Kaliningrad’s black diggers could earn $1,000 per month, equivalent to an upper-class income in economically depressed Kaliningrad.

Apart from bribes, black diggers had few expenses. Offshore divers needed only SCUBA or hookah gear and a dinghy; land diggers got by with picks, shovels, hoses, and salvaged automotive water pumps and engines. Miners would dig shallow shafts through soft sediments to reach the blue-earth layer, make a water mud, then pump it out to recover the amber, which floated atop the mud. Nor did black diggers have any environmental expenses; with the conclusion of mining, they simply walked away from the barren, mud-covered wastelands.

In 2014, when Kaliningrad’s black diggers were collectively matching the entire production of the Kaliningrad Amber Combine, a new player appeared in the amber industry 400 miles to the south—Ukraine. Amber occurrences had long been known to exist in Ukraine, particularly in the northwest, where amber was found on the surface after rains or collected during road-construction projects or agricultural plowing. But unlike the Baltic States, Ukraine had never developed an amber culture or industry. While Ukrainians occasionally carved amber, they used it primarily as a fuel. Amber mining, what little there was of it, was entirely unregulated.

the entire production of the Kaliningrad Amber Combine, a new player appeared in the amber industry 400 miles to the south—Ukraine. Amber occurrences had long been known to exist in Ukraine, particularly in the northwest, where amber was found on the surface after rains or collected during road-construction projects or agricultural plowing. But unlike the Baltic States, Ukraine had never developed an amber culture or industry. While Ukrainians occasionally carved amber, they used it primarily as a fuel. Amber mining, what little there was of it, was entirely unregulated.

After the 1991 Soviet collapse, a newly independent Ukraine, desperate to boost its dismal economy and create jobs, tried to replicate the Kaliningrad amber experience by opening a state-owned, open-pit mine and an amber-working facility. But, mired in inefficiency and corruption, the venture made little progress. By 2000, as amber prices continued to rise, Ukrainians began mining amber illegally and smuggling it to sell in Poland.

Then, as amber prices hit historic highs in 2014, Ukraine was rocked by political protests and a military invasion by Russian. As unemployment soared, thousands of Ukrainians took up picks, shovels, hoses, and salvaged automotive engines and water pumps to become illegal amber miners.

Emergence of Unlicensed Ukrainian Mining

By 2016, more than 10,000 unlicensed miners were digging up the pine and birch forests of northwestern Ukraine—aptly referred to as the “Wild West”—and finding far more amber than anyone expected. Unable to stop the growing rush, the police instead began selling “protection” services.

The annual income of many Ukrainian amber miners is now estimated at $8,000—four times the nation’s average yearly income. Another enticement for miners is the chance of hitting it big. In April 2019, a team of eight miners sank a crudely timbered shaft 12 feet deep. After a week of dreary, dirty, and dangerous work, they recovered 35 pounds of top-quality amber that they sold to middlemen-smugglers for $50,000.

Meanwhile, Ukraine’s state-controlled amber “industry” could not compete with the black market. Its official mine production in 2018 was a mere one ton, not enough to satisfy its own manufacturing needs. Mine and production-site managers had sold part of the state-owned amber on the black market.

Ukraine’s annual amber production is unknown, but the government’s State Service of Geology and Subsoil pegs it at about 300 tons with a black-market wholesale value of $50 million. The service also estimates that the Ukrainian government loses $50,000 per day in tax revenues. An even more significant loss results from the environmental damage to the expanses of forest and farmland that have been devastated by uncontrolled mining, along with the social costs due to crime and violence.

About 30,000 northern Europeans now work in the regional amber industry, mostly as illegal miners. Some work for the state combines or as middlemen, craftsmen, and retailers while others still run the smuggling networks. Illegal Kaliningrad amber is smuggled into Poland and Lithuania, while most Ukrainian amber is smuggled into Poland. European border checkpoints seize an estimated 50 tons of illegal Russian and Ukrainian amber each year.

At least 80 percent of northern Europe’s amber ends up in China. Chinese buyers want only raw amber that craftsmen fashion into styles preferred by Chinese consumers—a policy that undermines the state-controlled amber-manufacturing facilities in Kaliningrad and Ukraine. Meanwhile, Poland recovers only five tons of amber annually, mostly from beaches. Yet, the Polish city of Gdask on the Baltic coast remains the center of the international amber trade—where Chinese and other wholesale buyers sort through huge piles of smuggled amber.

This story about Baltic amber previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe! Story by Steve Voynick.