At Penn Dixie Fossil Park and Nature Preserve in Blasdell south of Buffalo just off Exit 56 on the New York State Thruway, the remains of a 380 million-year-old undersea world of Devonian brachiopod, crinoid and trilobite fossils are waiting to be found. Here time travel exists.

The 54-acre Penn Dixie Fossil Park (site of a former cement quarry that exposed multiple ancient layers of rock) earned the Guinness World Record™ in 2018 for the World’s Largest Fossil Dig (905 participating diggers) and a 2011 scientific study (published by the Geological Society of America, and authored by Dr. Renee M. Clary, Dept. of Geosciences, Mississippi State University and Dr. James Wandersee, Dept. of Educational Theory, Policy and Practice at Louisiana State University) ranked it the #1 fossil park in the U.S.

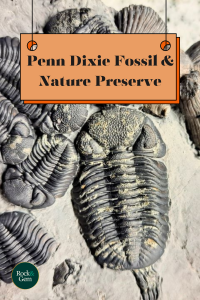

“Our trained staff and volunteers can guide your journey through the layers in search of fossils. Penn Dixie Fossil Park is famous for its trilobites – extinct arthropods that dominated the seas for 270 million years – but other fossils are just as plentiful if you know where to look.

“Visitors are welcome to keep any fossils they find, though we do ask for photos of really cool specimens, and offer help with collecting, tools for digging, and cards to help identify your fossils,” says Sydney Mecca, marketing and development coordinator for Hamburg Natural History Society/Penn Dixie.

Potato Bugs of the Ocean

Potato Bugs of the Ocean

What makes Penn Dixie Fossil Park the perfect family trip?

Its hands-on history recounts how North America and Europe, while still a single submerged land mass south of the equator, hosted reef ecosystems replete with brachiopods, horn corals, and those skittering and scavenging “potato bugs of the ocean,” trilobites.

“Our most sought-after fossils are trilobites,” Sydney says. The most commonly found at Penn Dixie are Eldredgeops rana (formerly Phacops rana), Greenops, and the more rare Bellacartwrightia.

Trilobites began appearing over 500 million years ago, at the beginning of the Cambrian Period, and were among the most successful marine forms of life, with more than 22,000 species described before their mass extinction at the end of the Permian Period. Their closest modern-day relative is the horseshoe crab.

Dig In

Dig In

“We have a lot of amateur collectors and families who come here for a fun way to spend a day. Of course, we get ‘doubters’ but then they start digging, and before they know it, they’re filling a bucket,” chuckles Sydney, whose work on-site during the season includes leading student field trips.

“We’re a big destination for the kiddos,” she says and seeing fossils through their eyes never gets old. “It’s fun watching second graders find an Eldredgeops rana. At first, they’ll say it looks like some kind of bug they already know about, and then I’ll tell them it’s actually 380 million years old (but I like how they’re thinking)!”

She also sees how amateurs of every age get excited over finding their own fossils.

“I know it sounds corny, but the best part of my job is the people. The camaraderie I see is amazing among people who start out as strangers but, by the end of the day, rocks and dirt have brought them together.”

The Nitty-Gritty

Penn Dixie Fossil Park opens for the season on the last weekend in April.

Its biggest event of the year is the first weekend in June: Dig With The Experts. This often-sold-out event (hint, reserve early) begins with an excavator coming into the quarry site to unearth fresh fossil hunting material.

The coveted opportunity to boldly dig where no man has dug before includes volunteer experts in geology and paleontology on hand to identify finds, plus digging experts, equipped with rock saws, to help hunters go deep in search of treasures.

Once “first dibs” at Dig With The Experts is over, the freshly overturned fossil sites are open to the general public for the rest of the season.

Among the programs free with park admission that kids and amateurs can find here are Fossils For Beginners, offered two Saturdays a month over the summer, with small group instruction with fossil experts and a short course on rock splitting, and Solar Sundays, when you can check out safe telescopic views of our largest fiery star.

Penn Dixie Fossil Park is looking at the stars while also spanning oceans.

“We have been building relationships with a few international organizations,” Sydney says of groups aspiring to their own fossil parks in Kashmir (India) and, most recently, Ukraine. “They are looking to do similar endeavors. We’re open to collaborating in ways that make sense. “

Rock & Ready

Rock & Ready

Speaking of solar, Sydney has some tips to keep a day of fossil hunting from turning into a meltdown, starting with, “Bring sunhats and sunglasses. Seriously!”

A common first-timer mistake is underestimating how a shale quarry reflects sunshine as fiercely as a parking lot. And if you’re bending forward all day, looking into the dirt, you better have protection or risk burning your neck.

“Don’t worry,” she says, “we keep lots of sunscreen on site.”

Shale and open-toed shoes also aren’t a wise combination.

“Of course, you can wear whatever you want, but shale is sharp.” And hard, so if you’re making contact with the ground all day, wear long pants and consider gardener’s kneepads and/or a camping chair.

Please keep Fido at home, too. Pets, other than service animals, are not allowed, and, with no shade in the parking lot, nowhere to safely keep one all day.

Hardcore fossil hunters are easy to spot by the shade tents they’ve packed and pitched, and by their coolers. Hydrating is important in the sun and heat, so bring lots of water, especially for kids. Penn Dixie has a paved trail to the main digging site, that’s easy to roll a cooler along, just past the check-in.

Give it a Tri-Lobite

Give it a Tri-Lobite

Penn Dixie is recognized as a global geological treasure but it’s not sitting on its ancient laurels. Over the next two years, the park and nature reserve hope to attain the next stages in a transformative evolution: a larger pavilion and ultimately, an educational visitors center. The International Union of Operating Engineers Local 17 has donated its labor and expertise to put in a bigger, better parking lot.

“It’s exciting to see tangible steps take place,” Sydney says.

Her favorite fossil, the snail-like gastropod, is a perfect symbol of Penn

Dixie’s past and future. Gastropods are among the oldest (540 million years) known fossils, yet those of today are nearly unchanged from their Cambrian ancestors.

“When I see the fossil of a shell, I can imagine the perfect little sea snail inside. Then I look around and realize terrestrial snails are here now. Theoretically, at Penn Dixie, you can find the same creature today as from 380 million years ago.” Time travel just got a little easier. Learn more about Penn Dixie Fossil Park & Nature Reserve and sign up for its newsletter at penndixie.org.

This story about Penn Dixie Fossil Park & Nature Reserve previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by L.A. Sokolowski.