By Steve Voynick

Despite its mundane petrological classification as a mudstone, pipestone has a lot going for it. Its great workability, exceedingly fine grain, and attractive reddish-brown colors make it a fine carving medium.

More importantly, pipestone, also known as argillite and catlinite, has an extraordinarily rich history and great cultural significance. Sacred to many Native Americans, it is a symbol of tribal traditions and religions. And pipestone, also celebrated in Anglo-American art and literature, is the raison d’être of the National Park Service’s Pipestone National Monument in Pipestone, Minnesota.

Technically, pipestone is argillite, a mudstone that has undergone varying degrees of metamorphic alteration. As a lithified mud or ooze, it consists primarily of microscopic silt particles roughly 0.0025 inches (0.06 millimeters) in size and even smaller clay particles only 0.0008 inches (0.002 millimeters) in size. These particles are mainly those of sericite, a group of fine-grained, micaceous clay minerals derived from the weathering of orthoclase and plagioclase feldspars. These minerals specifically include pyrophyllite and kaolinite (both basic aluminum silicates), diaspore (basic aluminum oxide), and muscovite (basic potassium aluminum silicate).

Because it is devoid of quartz, pipestone has an approximate hardness of only Mohs 2.5 and can be scratched with a fingernail. With a specific gravity of 2.65, it is as dense as quartz. Pipestone occurs in uniform masses with occasional bedding planes. Its colors are sometimes slightly mottled and range from gray, black, and green to reddish and reddish-brown. The latter two hues are caused by tiny particles of hematite, or iron oxide, and are the classic and most prized pipestone colors.

Pipestone occurs at several North American localities in varying grades and colors. Its premier and most storied sources are the small quarries near the aptly named town of Pipestone, the seat of Pipestone County, located in the far southwestern corner of Minnesota near the South Dakota line.

Pipestone and the Sioux Quartzite Connection

Pipestone occurs as thin strata within a massive formation of Sioux Quartzites, a 1.8-billion-year-old, metamorphosed sandstone. Tough and durable, Sioux Quartzite is a fine-grained, hard, flinty rock with yellow-to-reddish colors. Extremely erosion-resistant, it forms the bedrock over much of the Minnesota, South Dakota, and Iowa tri-state region.

Sioux Quartzite originated as quartz sand laid down by a large river-delta system. During this long deposition process, occasional decreased water flows carried smaller, quartz-deficient, silt- and-a clay-sized, micaceous particles that accumulated in thin strata. The thick layers of quartz sand later lithified into sandstone, while the thin strata of silt and clay particles lithified into mudstone.

Additional heat and pressure of deeper burial eventually metamorphosed (fused) the sandstone into quartzite, and partially altered the thin mudstone layers into argillite or pipestone. In more recent geological time, erosion and glaciation of the uppermost layers of the Sioux Quartzite exposed sections of the pipestone strata.

Pipestone was an ideal material for carving, and anthropologists believe that ceremonial smoking with carved, stone pipes had become part of Native American culture, particularly in the northern Great Plains, by 1500 BCE. It is not known when southwestern Minnesota’s pipestone outcrops first attracted attention as a pipe medium, but archaeological evidence suggests that quarrying was underway by 1000 BCE. Pipes and other artifacts fashioned from Minnesota pipestone recovered from Hopewell Culture mounds in Ohio suggest that pipestone had become a trading commodity by 200 BCE.

Tribal Significance

Pipestone has always had spiritual significance. It entered into the creation stories of various tribes, most of which attributed its reddish color to the spilled blood of warriors or buffalo. As pipestone and pipestone pipes became sacred, many tribes believed that the smoke from these pipes carried one’s prayers to the Great Spirit. Archaeological recoveries and Native American oral tradition both indicate that many tribes used the Minnesota quarries, even enemies who laid aside their weapons to quarry pipestone together in peace.

In his 1933 book “Land of the Spotted Eagle,” Lakota Sioux Chief Luther

Standing Bear explained the significance of pipestone. “All the meanings of moral duty, ethics, and religious and spiritual conceptions were symbolized in the pipe,” Standing Bear wrote. “It signified brotherhood, peace, and the perfection of [the Great Spirit], and to the Lakota the pipe stood for that which the Bible, church, state, and flag, all combined, represented in the mind of the White Man.”

Pipestone quarrying increased among Native Americans after Anglo contact made iron tools available in the late 1700s. By then, the Yankton Dakota Sioux controlled the quarries, and the Sioux, Ojibwe, and Pawnee had become master pipe carvers, and the simple tubes of earlier pipes had evolved into more complex elbow, disk, and T-shaped forms. Because of their appearance when connected to long stems, the T-shaped pipes became known as “calumets,” from the French chalameau, or “long flute.”

The growing numbers of Anglos arriving on the northern Plains saw that calumet pipes had ritualistic uses in every phase of war and peace, and were often smoked at treaty ceremonies. They began calling these pipes “peace pipes” and, in 1805, coined the word “pipestone” for the stone from which they were carved.

Until the early 1830s, the Native American peace-pipe tradition was known only to regional Anglo trappers, explorers, and traders. But in 1836, ethnographer, author, and artist George Catlin (1796-1872) visited the quarries. Catlin had previously befriended William Clark of the earlier Lewis and Clark expedition. Clark later became the federal Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Western Tribes and had amassed a large collection of peace pipes. Intrigued by Clark’s collection, Catlin was determined to visit the source of the pipestone.

Mining in Minnesota

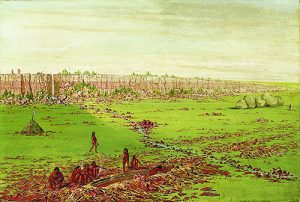

Catlin recorded his impression of the Minnesota pipestone quarries in one of his most famous paintings “Pipestone Quarries on the Coteau des Prairies (Pipestone Quarries on the Highland of the Prairies).” This oil-on-canvas landscape depicts Native Americans at the quarries and now hangs in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American Art in Washington, D.C. Catlin’s 1841 book “Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Conditions of the North American Indians” provided the first detailed, printed description of the pipestone quarries and their associated Native American legends.

Catlin also collected specimens of pipestone, which he erroneously believed were a “new form of steatite” (soapstone). A Boston mineralogist later described Catlin’s specimens as a “new mineral material,” which he named “catlinite” in Catlin’s honor. This name is still used today.

In 1847, many states, territories, cities, nations, and private groups were asked to contribute “memorial stones” for the construction of the Washington Monument in the nation’s capital. These stones were to represent in some way the contributors’ resources or heritage. Minnesota Territory (it became a state in 1858) provided a 2.5-foot-long pipestone slab which, along with 193 other memorial stones, was set into the monument’s interior walls where it can be seen today.

Inspired by Catlin’s paintings and writings, the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882) prominently mentioned the pipestone quarries and peace pipes in his 1855 epic poem “The Song of Hiawatha.” Part of this fictional account of an Ojibwe warrior opens with: “On the Mountains of the Prairie/On the Great Red Pipestone Quarry . . .’

In 1856, as “The Song of Hiawatha” gained national prominence, a federal treaty granted the Yankton Sioux “free and unrestricted access” to the “Great Red Pipestone Quarry” and a small tract of surrounding land. But from their South Dakota reservation, the Yankton had no direct control of the quarries. So others began quarrying the pipestone, including the Northwest Fur Company which, between 1864 and 1866, manufactured and traded 2,000 pipes.

Striving for Protection of Quarries

Meanwhile, the town of Pipestone, just a mile from the quarries, was platted in 1874 and quickly grew into a regional transportation and commercial hub. The town was built largely of quarried blocks of yellow and pink Sioux Quartzite. Much of its distinctive, original stone architecture still stands today.

In 1892, the federal government disregarded its treaty with the Yankton Sioux by illegally establishing the Pipestone Indian School on the quarry reservation, thereby passing de facto control of the sacred quarry to the Anglo school superintendent. The Yankton last worked the quarry in 1899, and all quarrying halted in 1911.

In the 1920s, the Yankton sued the government, claiming absolute title to the quarry land. In response, the government claimed that the treaty was merely an easement for limited use. In the end, the United States Supreme Court upheld the Yankton claim and awarded the tribe financial compensation. Ironically, accepting the compensation meant ceding the quarry land to the National Park Service.

In the 1930s, a Native American group, the Pipestone National Park Association, began urging the National Park Service to develop the site into a national monument to protect the quarries. And in 1937, as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal program, Congress established Pipestone National Monument. In 1947, the National Park Service implemented a permit system for quarrying pipestone that was open exclusively to registered members of Native American tribes.

Meanwhile, post-war automobile tourism was rapidly growing and Native American cultural and historical sites were becoming major points of interest. Capitalizing on the nearby pipestone quarries and the enduring popularity of Longfellow’s “The Song of Hiawatha,” Pipestone established a “Hiawatha Pageant” in 1949. A major regional attraction, this annual pageant, a reenactment of Longfellow’s poem, was performed continuously until 2008.

Migration Influences Pipestone Popularity

Also during the post-war years, numbers of Native Americans began migrating back to Pipestone to earn their livelihood by quarrying pipestone and selling pipes. In 1955, the Pipestone National Park Association, now the Pipestone Indian Shrine Association, opened a shop in the Pipestone National Monument Visitor Center and aided the national monument in developing educational and interpretive displays.

In the 1970s, many Native Americans joined the American Indian Movement to, among other goals, seek better control over their sacred sites, including Pipestone National Monument. In its early years, the national monument’s displays reflected a 1950s-era, Anglo perspective that presented certain stereotypical images that offended many Native Americans. These displays overemphasized the historical significance of George Catlin and other Anglo, rather than focusing on Native Americans themselves. In the 1990s, the National Park Service finally changed its visitor-center exhibits to more accurately depict Native Americans and their culture.

In 1996, a local group of Native Americans founded the Keepers of the Sacred Tradition of Pipemakers, a nonprofit organization not connected with the national monument. Its goal is educating the public about the past and present of the pipestone quarries and the pipe-making tradition. The Keepers collect and archive tales and lore related to pipestone and pipe making, present lectures and storytelling classes, and conduct hands-on pipe-making workshops and other activities. Its members have even traveled abroad to promote a better understanding of pipestone, pipe making, and other aspects of Native American culture.

Today, Pipestone National Monument manages 56 pipestone quarries on a permit basis. But with more than 100 applicants now on the waiting list, permit approval can take years.

Pipestone quarrying is the most underappreciated part of the pipe-making tradition. To many Native Americans, quarrying is a spiritual experience that provides direct connection with the Earth, the quartzite, and the pipestone itself. Quarrying is a slow, laborious process that, by federal regulation, can employ only simple tools such as sledgehammers, pry bars, wedges, and chisels. Today’s quarrying process is basically the same as it was centuries ago.

Time Needed to Expose Pipestone Layers

Depending on the particular quarry and the quantity of overburden

(Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

material that has already been removed, as many as six weeks can be needed to expose a small part of the pipestone layer. On average, six feet of soil and glacial debris lie atop a four-to-ten-foot-thick section of solid Sioux Quartzite—all of which must be removed to reach the pipestone.

Quarriers use picks, shovels, and wheelbarrows to remove the unconsolidated surface material. Then the real work begins with hammers, wedges, and chisels to exploit natural, vertical cracks and break apart blocks of quartzite, which are then hammered into smaller pieces and carried to the back of the quarry. This break-and-remove procedure must be repeated many times to expose the pipestone layer.

The pipestone layer, which is 10 to 18 inches in overall thickness, consists of thinner, multiple layers separated by bedding planes. Quarriers drive wedges into these horizontal bedding planes to separate the layers. Because the natural, vertical cracks in the overlying quartzite extend through the pipestone, it is removed in irregularly shaped pieces only a few inches thick and rarely more than one foot long.

With the quarries located in a bowl-shaped drainage, water from spring snowmelt and summer rain often fills the diggings with water. Most quarrying is done in summer and fall when groundwater problems are minimal.

Pipestone National Monument covers 282 acres and now welcomes 70,000 visitors per year. Its visitor center has a museum and cultural center which, from April through mid-October, presents interpretive programs and cultural demonstrations, the latter featuring Native American artisans who fashion pipes from pipestone. Hiking trails pass pipestone quarries that can be active in summer or fall. Visitors can purchase both rough pipestone and finished pipes at the national monument’s shop, which is operated by the Pipestone Indian Shrine Association.

Drawing Debate

The sale of pipestone and pipestone pipes is not without controversy. Some Native Americans believe that selling pipestone in any form to the public disregards the stone’s sanctity. Others believe that selling pipestone is acceptable, and point out that the sacred stone has been traded for centuries.

The manner in which pipes are displayed is also debated. Some believe that displaying “joined” pipes (pipes connected to the stem) is disrespectful to, and ignorant of, Native American culture. They consider joined pipes to be spiritually “awakened” and thus should be used only for prayer or ceremony. Others believe that displaying joined pipes does not compromise the pipes’ sanctity.

Meanwhile, the Yankton Sioux, citing its 1856 federal treaty and the questionable manner in which the National Park Service acquired the quarry land, continue to claim absolute title to the quarries and the land currently occupied by Pipestone National Monument.

So this particular variety of mudstone, whether known as pipestone, argillite, or catlinite, has quite a story behind it. Pipestone quarrying and the making and using of pipestone pipes are among the great Native American traditions. And they are alive and well in Pipestone, Minnesota, at Pipestone National Monument, and with the Keepers of the Sacred Tradition of Pipemakers.

For further information about Pipestone National Monument, visit www.nps.gov/pipe. The website for the Keepers of the Sacred Tradition of Pipemakers, which maintains a gift shop and gallery at 400 N. Hiawatha Avenue near the national monument, is www.pipekeepers.org.