Platinum metal in just the past century has gone from rags to riches, overcoming its checkered past, finding many uses in everyday life, science and industry, gaining acceptance as a jewelry and investment metal, and at times even surpassing gold in value.

Throughout history, the precious metals gold and silver have been admired for their beauty, hoarded for their value, coveted for their workability, fashioned into jewelry, and coined as currency. But the story of platinum metal is much different. It was once cursed, discarded as worthless and used as a counterfeiting agent.

Platinum Metal

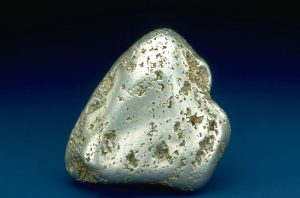

Platinum is a rare, silvery-white metal. Its specific gravity of 21.45 and Mohs scale of hardness of 4.0 make it somewhat more dense and much harder than gold. Although not as quite as inert as gold, it nevertheless does not oxidize, retaining its gleaming, white metallic luster and taking a superb polish. Platinum also has excellent electrical conductivity, corrosion resistance, and catalytic properties, plus a high melting point. Platinum is about as rare as gold but, unlike gold, it is rarely found in economic concentrations suitable for mining. Platinum occurs in some 20 minerals and is also found in nature, usually as silvery-gray grains and nuggets.

Johnson Matthey

Platina

In the early 1500s, Spain’s colonial gold miners, in what is now Colombia, found platinum in gold placers. They roundly cursed this discovery because the metal then had neither use nor value and was difficult to separate from gold. The Spanish named the metal platina, a derogatory term meaning “little silver” and the root of our English word “platinum.” In the early 1600s, Spanish mint workers at the future site of Bogotá, Colombia, dumped large amounts of worthless platina into rivers to create extraordinarily rich placer deposits that would end up being mined centuries later. In 1670, Spanish metallurgists found platina’s first practical use as an alloying agent to enhance the hardness and durability of bronze cannon.

In 1700, metallurgists learned that gold alloyed with platina changed very little in weight or color. Spanish mint workers subsequently began adulterating gold coins with platina and pocketing the displaced gold. To suppress this rampant counterfeiting, the Spanish Crown banned private possession of platina under penalty of death. But when counterfeiting continued, it began offering a bounty for all platina turned in, giving the metal its first formal valuation. The Crown later secretly debased its own gold coinage with platina, using these “special” issues to settle foreign debts.

Johnson Matthey

The Russian Experience

In 1824, Russian gold prospectors in the Ural Mountains discovered the rich Nizhne-Tagilsk platinum placers. The Russian government quickly monopolized platinum mining and refining, then began fabricating platinum jewelry which consumers promptly rejected as a cheap “silver imitation.” Determined to benefit from its platinum, the Russian government next issued legal-tender, platinum ruble coins. But by 1843, the number of circulating platinum rubles had far exceeded the official mint issues because European counterfeiters had been acquiring worthless Colombian platina and striking counterfeit rubles.

Wikimedia Commons

Coming of Age

During the 1850s, European scientists took advantage of platinum’s high melting point and chemical inertness to fabricate high-quality laboratory instruments and crucibles. Growing demand soon drove platinum’s price to $1.50 per troy ounce, higher than that of silver. By the 1890s, platinum’s extraordinary catalytic properties that accelerated many chemical reactions had made it the standard catalyst for acid manufacturing and petroleum “cracking.”

At the same time, platinum gained popularity as a jewelry metal when prestigious designers Louis Cartier, Charles Lewis Tiffany and Peter Carl Fabergé began combining platinum’s brilliant, white gleam with the glitter of diamonds and sapphires. By 1905, combined jewelry and industrial demand had driven platinum’s price above that of gold (then $20.67 per troy ounce) for the first time. Breaking the gold-price “barrier” earned platinum worldwide acceptance as a bona fide precious metal.

Industrial Platinum Metal

Platinum demand soared in the 1970s when federally mandated reductions in automotive exhaust emissions required new automobiles to be equipped with catalytic converters to break down noxious hydrocarbons and nitrous oxides. Today’s automotive converters contain about one-half a troy ounce of platinum in a ceramic honeycomb called “autocatalyst,” which is currently the biggest use of platinum. Eight million troy ounces of platinum are now mined each year, mostly in South Africa and Russia, with lesser amounts recovered in Canada and the United States. The United States’ production comes almost entirely from Montana’s underground Stillwater Mine.

Johnson Matthey

Jewelry Platinum Metal

About 1.5 million troy ounces of 85-to-95-percent pure platinum are made into jewelry each year. Platinum purity, expressed in parts per thousand, is stated in hallmarks similar to gold karat marks. A “Pt950” or “Plat950” hallmark indicates a composition of 95 percent platinum; the remaining five percent is usually copper or palladium which enhances workability. Platinum’s white gleam complements or contrasts nicely with both colorless and colored gemstones. Popular composite jewelry creations combine the rich yellow of gold with the gleaming white of platinum—a fitting combination for a metal that, in less than 120 years, has gone from rags to riches.

This story about platinum appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Steve Voynick.