Potosi silver mine history is a story of fabulous wealth and royalty mingled with abject poverty and a drama still playing out today at the lofty elevation of 13,400 feet in the Andes Mountains of southern Bolivia.

“I am rich Potosí, treasure of the world, king of mountains and envy of kings.”

Although these words on the coat of arms that King of Spain Charles V granted to the city of Potosí in 1557 might seem pretentious, they were actually somewhat understated. By 1600, Potosí, the biggest city in Spain’s Viceroyalty of Peru, was indeed the “treasure of the world” and the “envy of kings.” As the richest silver deposit that would ever be discovered, Potosí would yield a monumental fortune that would impact the world socially, politically, and economically.

Cerro Rico

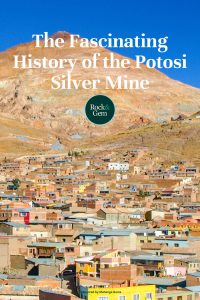

Potosi’s silver was emplaced within a reddish, cone-shaped mountain that the Spanish fittingly named Cerro Rico (Rich Mountain). This barren, 15,689-foot-high remnant of a 14-million-year-old volcanic dome was mineralized when superheated, silver-and-tin-rich hydrothermal solutions surged upward into the fractured dome.

Upon cooling, ore minerals precipitated in veins, with silver veins overlying those of tin. Because of its shape and low water table, Cerro Rico had an unusually large oxidation and enrichment zone where the original silver sulfide could alter into the silver-chloride mineral chlorargyrite.

This vein-hosted, polymetallic deposit, as geologists now describe it, consisted of a complex network of vertically oriented veins as thick as five feet. Many were extraordinarily rich and graded 40 percent silver by weight. A single ton of this ore, with a volume of just five cubic feet, contained as many as 12,000 troy ounces of silver.

Discovering Silver

When the Spanish learned of Cerro Rico in 1545, they couldn’t believe their good fortune. The ore was not only fantastically rich but extracting silver required only mining, crushing, and simple smelting in crude ceramic ovens.

This operation was nevertheless labor-intensive. The Spanish acquired workers through their “mita” system of recruiting indigenous people for forced labor on a rotational schedule. By 1560, with 3,200 laborers mining, crushing, and smelting ore, Potosí was shipping five million troy ounces of silver per year.

By then, however, the richest and most accessible ores were already gone and silver production had begun to decline sharply. Although enormous amounts of silver mineralization remained within Cerro Rico, it was too low in grade for direct smelting, and no method of large-scale concentration yet existed.

“A Match Made in Heaven”

But Spanish smelter workers in Mexico had just developed the so-called “patio process” by spreading crushed, low-grade silver ore on cobblestone patios (hence the name) and mixing it with mercury, salt, and copper sulfate. The ensuing chemical reaction reduced the ore to metallic silver which formed an amalgam with the mercury. Heating the amalgam then drove off the mercury, leaving behind metallic silver of high purity.

Cerro Rico’s low-grade ores were well-suited to this new recovery method. But the patio process required large amounts of mercury which, at the time, were obtainable only from distant Almadén, Spain.

Then in 1560, in one of history’s most fortuitous coincidences, Spanish prospectors at Huancavelica, 700 miles north of Potosí in present-day Peru, discovered large deposits of cinnabar, the only ore of mercury. The newly founded city of Huancavelica soon had a population of 30,000 residents, most working directly or indirectly to support cinnabar mining and the shipping of mercury.

Pack trains hauled the mercury over rough trails to Potosí where it dramatically extended the life and increased production of the Cerro Rico mines. One Spanish writer described the combination of Huancavelica mercury and Potosi silver as “a match made in heaven.”

“The Treasure of the World”

By 1650, Potosí, with a population of 160,000, was bigger than most major European cities. As the world’s largest industrial complex, Potosí had hundreds of tunnels and shafts, along with 22 artificial reservoirs that provided water power to 120 crushing mills, 60 amalgamation patios, and 6,000 ceramic kilns to heat amalgam and recover the silver.

The center of Potosí, a mix of cathedrals, villas, and imposing colonial architecture, was dominated by the Crown mint which converted silver into 16-pound ingots and millions of crudely shaped, eight-reales coins. These fabled “pieces of eight” quickly became the standard of exchange in world trade.

Between 1545 and 1810, Potosí alone accounted for more than one-third of the world’s silver production, making Spain the richest of all nations and bolstering the economies of Europe and much of Asia. Potosi silver facilitated the rapid expansion of international commerce, bankrolled wars that redefined national borders and was the basis for the development of a modern global economy.

Because of the corrupt Spanish mining system, rampant theft and smuggling, and lost or fraudulent records, historians can only estimate how much silver Potosi produced. The documented output stands at 765,000 troy ounces, but historians agree that the actual figure could approach two billion troy ounces (about 90,000 tonnes).

The Dark Side of Potosi

Conditions within the Cerro Rico mines were horrific. The combination of unventilated underground air—hot, humid, and laden with oil-lamp smoke and rock dust—and the cold, dry surface air meant pneumonia and other respiratory ailments were rampant. These factors, together with the extreme exertion required to break rock manually and haul heavy bags of ore up ladders of frayed rope and rotted wood, inflicted soaring mortality, injury, and sickness rates among the indigenous forced laborers.

Surface workers faced a different but no less deadly hazard—mercury. When ingested, absorbed, or inhaled in sufficient quantities, mercury, its vapors, and many of its compounds are toxic and can cause severe physical and mental debilitation, and even death. Each day, workers in the amalgamation patios and retorting operations were exposed to mercury on a massive scale. Thousands died or suffered severe debilitation because of what was then called “mercury sickness.”

The overall mortality count at Potosí will never be known, but conservative estimates of the deaths attributed directly to mining silver and retorting amalgam over 260 years are far over one million.

Potosi Today

In 1825, after 15 years of revolutionary struggle against Spanish oppression, the great liberator Simón Bolívar symbolically proclaimed South American freedom from a most fitting place—the summit of Cerro Rico. By then, Cerro Rico’s silver ore was pretty much depleted, although sporadic mining continued, mainly for tin.

The nationalized Bolivian mining company Corporación Minera de Bolivia mined tin at Cerro Rico until 1980. But after a tin market crash closed the big mine, hundreds of unemployed miners began to form loose cooperatives, lease sections of Cerro Rico from the government, and engage in unregulated, independent mining.

Today, an estimated 12,000 independent miners associated with 300 small cooperatives work in some 500 individual mines on Cerro Rico in conditions not unlike those of the colonial era. Miners rely on tobacco, alcohol, and coca leaves to get through the long, dark shifts. Accidents, often caused by the collapse of centuries-old tunnels, claim about 20 lives each year. Cerro Rico miners also use the supernatural to cope with their dismal working conditions. El Tío (the Uncle) is their Lord of the Underworld, and representations, fashioned from clay, wood, cardboard, or paper-mâché, are present in every mine. Miners believe that these garishly painted, demonic figures with their horns and bulging eyes if appeased with daily gifts of tobacco, alcohol, and coca leaves, will protect them from injury or death, and lead them to valuable minerals.

The Future of Potosi

After nearly five centuries of continuous mining, Cerro Rico, a relatively small mountain now honeycombed with more than 125 miles of tunnels and shafts, has become geologically unstable. A wide subsidence crater recently appeared near the summit as the mountain began collapsing into itself, triggering fears that a massive collapse could kill hundreds of miners.

In 1987, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) added Potosí and Cerro Rico to its list of World Heritage Sites. But because of its increasing geological instability, Cerro Rico has now been moved to the list of Endangered Heritage Sites.

Despite the mountain’s growing instability, miners find that guiding underground tour groups can be more profitable than mining the remaining ore. This is making Cerro Rico a trendy destination for adventure tourism, where visitors, equipped with rented rubber boots, hard hats, and cap lamps, can explore some of the world’s most historic underground mine workings—but only after leaving gifts for El Tío.

This story about Potosi silver mine history previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Steve Voynick.