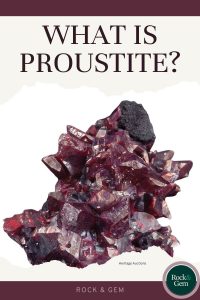

What is proustite? Commonly called “blood of the bull” or “ruby silver” scarlet proustite is a hard-to-find silver compound and a sulfosalt mineral.

Seldom-Seen Silver Compounds

The red color of proustite and pyrargyrite (both silver compounds) makes them the most appealing and eagerly sought silver species. Collectors are overjoyed when they obtain a specimen of either of these silver compounds since today’s silver mines rarely encounter such specimens. Many found in the early centuries of silver mining have long since ended up in museums or in private collections.

Of the two, proustite exhibits the richest red color and when found in quantity in Chanarcillo, Chile, was given the name Sangre de Torro, or Blood of the Bull. Pyrargyrite is a somewhat darker red color and is still occasionally found today in the silver mines of Mexico.

Finding Proustite in Mexico

Some 30 years ago, I was traveling in Mexico visiting silver mines including the mine at Fresnillo, Chihuahua, Mexico.

Prior to going underground, my party was escorted through the mill by an engineer. As we stood by the conveyor belt watching silver ore come from the depths, I asked the engineer if proustite or pyrargyrite crystals ever showed up on the conveyor belt.

He said they did and they would pick them up. I asked what he did with what he collected, expecting a positive answer. I almost fell on the belt when he said they save the red silver crystals so when the silver production numbers drop below expectations, they toss the collected red silver specimens on the belt to “sweeten” the production numbers. I never got over that comment!

Heat & Light Sensitive

Pyrargyrite is a silver antimony sulfide and proustite is a silver arsenic sulfide. Proustite has a Mohs-scale hardness of 2 to 2.5. Both species are rare, with pyrargyrite a little more common and a slightly darker shade of red.

Unfortunately, both these silver minerals are heat- and light-sensitive, tending to darken when exposed to strong light.

(ROB LAVINSKY, iROCKS, WIKIMEDIA COMMONS)

These external influences only hasten an inevitable internal change that gradually happens regardless of external influences. Research has shown that the darkening of these species can even happen regardless of careful protection from long exposure to light because of a slow, natural darkening process. This is because another mechanism is at work.

In the crystal structure of proustite and pyrargyrite, silver atoms are not locked in place. They tend to move, and that causes them to begin to form a second mineral internally within the red crystals. This movement is because of a thermal effect and it happens regardless of the external protection given the red silvers.

Thermal-Related Development

The thermal effect actually causes silver to develop another mineral, forming dark gray silver sulfide, acanthite. As this dark mineral becomes an integral part of the red crystal’s internal structure, it affects a slow color change, unlike so many minerals that change color only because of external influences like radioactivity, heat or light. Since the color change in proustite and pyrargyrite is an internal function causing the darkening of color, the internal change is permanent and cannot be reversed.

Proustite Popularity

I’ve been lucky enough to handle and own quite a few specimens of these two silver species. Of the two, proustite is my favorite for perhaps the oddest of reasons. Yes, it has the richest red color. Yes, it forms extremely attractive, tapering hexagonal crystals. True, the finer tapering crystals resemble red dog tooth calcites. But proustite is my favorite because of a single proustite specimen that has no crystals at all.

The specimen is about five inches across, two inches thick, and maybe three inches front to back. It has a grayish acanthite exterior “skin” and was composed internally of a solid mass of red proustite. No crystals – just a solid chunk of red proustite. It is half of what probably was a proustite nodule mined well over 100 years ago in Colorado.

In my dozens of years of collecting, this solid mass of proustite is the only such mass I’ve ever handled. I first saw it about 1948 when I joined the New Haven, Ct., Mineral Club and met collector Russ Jones. While visiting him, he brought out a piece of black velvet cloth wrapped around a rock. The rock turned out to be that solid mass of red proustite described above.

Inherited Treasures

Fast-forward to the 1990s when Russ’s health was so bad, he was close to death. I was in Arizona when I got a call from Russ’s lawyer, who informed me that Russ was in a nursing home and wanted me to put his collection in storage. He wanted me to do it because he had willed his collection to me!

The specimen was not from one of the world-famous silver mines like Kongsberg, Norway, Chanarcillo, Chile, or Saxony, Germany. It had been mined in the late 1800s in Colorado in a Fall River District mine, Clear Creek County west of Denver. Even when it was found, it was considered so unusual that it was actually put on display in a local library. At some point, a Denver mineral dealer, Mitch Gunnell, came into possession of it, and when he advertised it for sale, Russ Jones, who loved Colorado minerals, bought the piece for $200.

Where is Proustite Mined?

While some Colorado silver mines did produce proustite of note, the major sources of proustite are far better known in the collector world and include Germany’s Saxony and Harz Mountains, Joachimthal, Bohemia, and most important of all, Chanarcillo, Chile. Each of these localities yielded clusters of superb proustite crystal groups as well as fine single and small sprays of crystal clusters.

Keep in mind that these mines, except for Chanarcillo, were first discovered starting over 1,000 years ago. Specimens from these mines that you see today are old. They have been out of the ground for many hundreds of years in some cases, so lack the vibrant color they originally had.

One of the more important producers was the Dolores mine in Chanarcillo, Chile. Lucky is the collector who has a colorful Dolores Terera mine proustite.

An Accidental Discovery

The silver deposits of Chile were accidentally discovered by Juan Godoy in 1832. The silver species Godoy actually found was chlorargyrite, a silver chloride that is easily scratched with a fingernail and is usually a dull, waxy material. The chlorargyrite led him to the Chanarcillo silver veins and silver mining boom in the area from the 1830s to about 1890.

During the more productive years in Chanarcillo, miners had breached the supergene environment where proustite most often forms in quantity. The high heat and pressures of the supergene zone facilitate proustite formation.

(Heritage Auctions)

Specimens of proustite from Chile can be seen today in most museums as well as in private collections. I can recall visiting the Peabody Museum of Harvard in the 1980s and enjoying the lovely suite of proustite specimens well-protected in a wooden lidded box. You had to lift the lid to view the proustites. Today we now know such protection only delays but does not stop the slow darkening of proustite.

Though proustite specimens are rarely available today, collectors keep searching. To know better what you are looking for, I suggest you check the Terry Wallace article “Seeing Red: The Addictive Allure of Proustite.”

This story about what is proustite appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Bob Jones.