A psammophile knows that while rock and mineral collectors often seek the biggest crystal ever, true wonders exist at the microscopic level. A single teaspoon of sand from a beach, riverbed or desert dune can hold a world you never imagined when viewed through the lens of a microscope.

A whole community of fellow enthusiasts exists to exchange these tiny bits of amazing nature from around the world. You can join that community. But beware. Once you start, it’s all too easy to get hooked!

Psammophile Sand Collectors Defined

People who are fascinated by and who collect sand wherever they can are called psammophiles, or arenophiles. The term psammophile is derived from the Greek words psammo (sand) and phile (lover of). If you prefer Latin over Greek, you would be an arenophile.

True-blue sand lovers not only carry ziplock baggies to scoop up samples, they dump out shoes after a walk across a beach or desert dune to see what treasures they may have gathered.

What is Sand?

A heap of sand is a collection of microminerals and/or microfossils with a grain size residing between silt and gravel. Precisely, “very fine” sand has a grain size of 0.0625 to 0.125 mm, and “very coarse” sand has a grain size of up to 2+ mm.

Sand often starts from rocks that weather and decompose. Sand is generally divided into three basic types derived from different sources.

- Minerals in Beach Sand: These include quartz and feldspar weathered and eroded from igneous rocks such as granites or from metamorphic rocks like quartzite (which is ultimately derived from sedimentary sandstone formed from sand).

- Grains Eroded from Chemical Precipitates: In ocean or lake waters, certain chemical elements or compounds can precipitate out and form beds of sedimentary material such as limestone. A prime example is gypsum sand from White Sands, New Mexico. You’ll also find carbonate sands along tropical and subtropical beaches like Florida.

- Biogenic Grains: These include grains from tropical and subtropical beaches with tiny shells of foraminifera and fragments of shell, coral, urchins and other biological (“biogenic”) bits. Shells from these once-living organisms have been battered, ground against one another, and washed and sorted by waves down to the size of sand grains.

The Varied Nature of Sand

Sand that has been transported by water and/or wind and ends up along a beach or in an area of dunes is often “well sorted.” That means it consists of rounded grains of uniform size and composition.

This is the case with nearly pure white quartz sands found in dune areas around the Monterey Peninsula in California that were once mined to produce optical glass, or the luxuriously soft white carbonate beach sands in parts of Florida and the Caribbean.

Sand that has not been transported far (as along a stream or a dry wash in a mountain valley) most often has rough, angular grains of varied sizes and minerals. Such sands are considered to be “poorly sorted.”

The color of sand comes from the color of its constituent minerals. For example, White Sands National Monument in New Mexico holds fields of pure white sand composed of gypsum, whereas Papakōlea Beach in Hawaii has green sand due to the mineral olivine.

You can also find pink or red sands with abundant garnet grains or black sands containing a high amount of magnetite or other iron minerals.

Collecting Sand

Sand collecting is easy! You can collect from beaches along thousands of miles of coasts in the United States. You can collect from desert dunes, including “ancient” dunes such as the Sand Hills of Nebraska. You can collect along streams and rivers or the banks of lakes, whether small or large, like the Great Lakes including Lake Michigan beaches.

However, please take note. In some places, sand collecting is regulated or even illegal. Don’t collect in national parks, for instance, or on beaches where “no collecting” signs are posted.

This applies to a famous “green sand” locality in Hawaii and White Sands National Monument in New Mexico. However, I would point out that in areas around the White Sands National Monument, sands drift out beyond monument boundaries and across many a highway surrounding the off-limits region.

Just be thoroughly informed of off-limit boundaries before whipping out a plastic sandwich baggie and scooping up a sample!

Four Ways for a Psammophile to Examine Finds

If you truly wish to become a psammophile, you need to move beyond merely collecting samples and invest in ways to examine those samples. It’s hard to get an up-close view of sand with the naked eye. Fortunately, assorted options exist for budgets large and small. Here are just a few examples:

#1 A simple 10X loupe or other hand magnifying glass.

This is the classic, inexpensive old-school standby of all geologists, whether professional or amateur. Don’t leave home without it!

#2 A binocular dissecting microscope.

A binocular microscope is the way to go if you want a truly good look at just what sorts of grains are contained within your sand sample. As an added benefit, many of these microscopes come with adaptors that allow you to attach a camera to photograph your finds.

#3 A macro lens feature or attachment to a cell phone camera.

Forget investing in a binocular microscope! Many cell phones feature a camera, as well as a macro feature. If you don’t have a macro feature already built into your cell phone, you can purchase a macro lens attachment to fit over your cell phone camera lens. (Many of the photos I took in preparing this article were done with just such an attachment.)

#4 A USB digital microscope.

I’ve purchased a unit called the “Dino-Lite Pro Digital Microscope” with a cable that attaches to my computer. It allows me to see even closer than my cell phone macro lens while also allowing me to take digital photos of what I’m seeing. A cool aspect of this is that you can attach it to a laptop and a projector to illustrate a talk in real time.

Obtaining one of these or other similar optical devices is an absolute prerequisite for the true psammophile. You can collect sand without these instruments, but to truly see what you’ve collected and to see what it’s composed of, you need the help of good, high-resolution magnification.

Storing Your Finds is Easy!

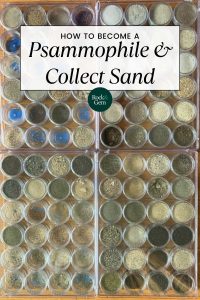

No doubt about it! When it comes to sand, you’ll experience no headaches regarding storage issues. Space requirements to house even a large and varied collection with hundreds of samples are minimal. How is this possible?

First, in collecting sand you don’t need to collect large quantities. Scooping just one or two tablespoons provides more than enough material from a locality to give you endless fun.

Second, individual samples can be stored in containers of relatively small and uniform size and shape, making it easy to stack and pack them in a flat or a box. Here are just a few examples of storage containers that psammophiles use.

- Film canisters

- Bead storage canisters from hobby and craft stores

- Test tubes with stoppers

- Plastic pill bottles

- Small glass bottles with snap-on or screw tops

It’s best to use hard plastic or glass containers like these, not ziplock-type baggies that can easily puncture or rip.

It’s important to affix labels to each of your containers with the very basic information as to what it is and where it came from. Additional info to consider might be the date of collection, who provided it (if traded) or anything else important to you.

Choose labels with adhesive on the back or glue your labels onto your containers. Pressure-sensitive plastic tapes like Scotch Tape tend to yellow over the years and come loose.

If you’re building a collection of your own, you just need small containers. If actively trading with fellow enthusiasts and collecting larger quantities, you can use leftover jelly, peanut butter, salsa, herb, or other jars kept from your groceries. Pay for the peanut butter. Get the jar for free!

Sharing Your Finds

Psammophiles are famously social. Once they stumble across fellow enthusiasts, they’re happy to exchange samples. Some even have goals of collecting from every U.S. state, continent, and/or nation on Earth and thus reach out to fellow collectors worldwide.

To further the exchange of interest and samples, enthusiasts formed the International Sand Collectors Society in 1969. It hosts an annual SandFest and publishes a quarterly newsletter, The Sand Paper.

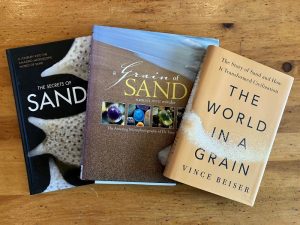

Sand Collecting Resources

There’s a lot more to sand than meets the eye in a hobby involving a lot of fun at little to no expense! |

This story about becoming a psammophile previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story and pictures by Jim-Brace Thompson.

good article