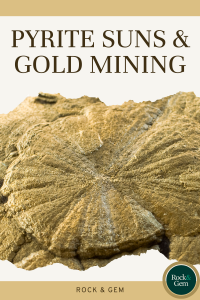

With their thin, flat, disk-like shapes, brassy color and bright metallic luster, “suns” are the most eye-catching and popular of all pyrite concretions. Concretions, a word derived from the Latin con, meaning “together,” and crescere, “to grow,” are growths of crystallizing minerals that have displaced sediments or filled pores in sedimentary rock. Concretions can be spherical, ovoidal, elongated, flattened, or irregular in shape and range in size from microscopic to several feet in diameter.

The Illinois Coal Fields

Suns are the rarest form of concretionary pyrite. Most pyrite-sun specimens, including the largest and finest, come from the vicinity of Sparta, Illinois, near the center of the vast Illinois Coal Basin. This basin of coal-rich, 300-million-year-old Pennsylvanian sediments covers central and southern Illinois and adjacent parts of Indiana and Kentucky. Since commercial mining began here in the mid-1800s, the Illinois Coal Basin has yielded more than nine billion tonnes of coal.

Near Sparta, the six-to-eight-foot-thick Herrin Coal Seam rests roughly 250 feet beneath the surface. Atop this coal seam is the Anna Shale, a massive layer of black, organic-rich, marine shale. The bituminous Herrin coal is rich in sulfur, while the Anna shale is rich in iron and sulfur. Under the heat and pressure of deep burial, the iron and sulfur combined into pyrite (iron disulfide) concretions that developed within shale laminations just above the shale-coal contact.

How Suns are Formed

Under most conditions, this pyrite would have formed roughly spherical nodules. But trapped under great pressure within the hard shale, the pyrite grew in the directions of least resistance — laterally within the horizontal laminations to form flat, disk-like suns.

Steve Voynick

Tiny pyrite suns, most only a fraction of an inch in diameter, are found in coal-shale environments worldwide. But pyrite suns from the Sparta-area mines are by far the most numerous, largest and best developed. Many are three to four inches in diameter; the largest are nearly eight inches in diameter.

The chemical stability of pyrite suns has long been debated. While some last indefinitely, others quickly display the unmistakable signs of pyrite oxidation — a sulfuric-acid odor and a slow crumbling into particles of iron hydroxides. According to the Illinois State Geological Survey, pyrite suns from the Sparta mines contain low amounts of marcasite, an orthorhombic polymorph of iron disulfide that oxidizes readily and likely accelerates the oxidation of the pyrite.

Sun Popularity

Sparta-area miners began collecting pyrite suns as novelty items in the 1800s. But not until the 1950s, when national interest in mineral collecting began growing rapidly, did strong commercial demand develop. Miners then began “high-grading” the suns. They carried them from the mines in their lunch buckets and sold them to mineral-specimen dealers.

Wikimedia Commons.

Iridescent pyrite suns became quite popular again during the 1990s. While suns occasionally exhibit natural iridescence, most that reached the market were treated with acid to artificially induce or to enhance iridescence. Unfortunately, treated iridescent suns show a much higher rate of oxidation than untreated specimens.

The Future of Pyrite Suns

The market supply of pyrite suns has always depended on coal mining. In the 1950s, Illinois had 27,000 coal miners and some 150 mines. Most were small, hands-on, underground operations that were ideal venues for collecting suns.

Coal mining has declined sharply as power plants moved away from coal, especially the Illinois Coal Basin’s high-sulfur coal. Today, only 2,700 Illinois miners work in 17 coal mines. Sparta’s Randolph County, where most pyrite suns are found, has only one underground and two surface mines. Because these mines are now highly mechanized, miners have few opportunities to collect pyrite suns.

Today, dealer supplies are still substantial and limited numbers of new specimens continue to come from the mines and shale-waste heaps. In the not-distant future, time may run out on both coal mining and the supply of pyrite suns.

This Rock Science column about pyrite suns and coal mining appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Steve Voynick.