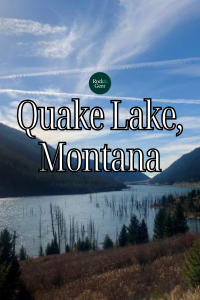

Quake Lake, Montana, and the earthquake that formed it created an indelible mark on the landscape and in the minds of those who lived through the event. It’s a lesson in the continually changing geology and the power of the seismic activity that lies beneath our feet.

Quake Lake, Montana: The Calm Before the Quake

August 17, 1959, was an idyllic, warm summer evening along the Madison River in Southwestern Montana west of Yellowstone National Park. There was a camaraderie among the campers basking in the picturesque setting and moonlit sky. Families became friends, dogs chased a black bear out of camp and up a nearby tree, and many enjoyed roasting marshmallows over their campfires at dark. Life couldn’t have been better… until 11:37 p.m.

A 7.3 magnitude earthquake hit the Hebgen Lake region causing the mountain at the mouth of the river, close to where it flowed toward the prairie, to break lose carrying roughly 50 million cubic yards of rock 100 mph hour down the slope partially burying Rock Creek campground as it flowed up the north side of the canyon. Hurricane-force winds ahead of the slide snapped trees that were four feet in diameter, tossed the enormous cars of the day, along with people and debris, and the blocked Madison River immediately began flooding the area.

Larry E. Morris, historian and author of the book, The 1959 Yellowstone Earthquake, quoted survivor S. B. Gilstad who rightly stated, “The roar sounded like the end of the world.”

The Nightmare Begins

And this was precisely the case for 19 people camped at the Rock Creek Campground who were instantly buried under 73 million metric tons of rumble. But for the over 250 people staying in the Madison River Canyon area, the initial quake was just the beginning of a harrowing ordeal.

Ellen Butler, Earthquake Lake Visitor Center manager and co-author of Images of America: Earthquake Lake, said this was a popular recreation spot during the summer.

“There were multiple resorts in the area. The Campfire Lodge is still there. Rock Creek Campground was over capacity so people were camping all over the place.”

Registered nurse Mildred “Tootie” Greene, along with her husband Ray and nine-year-old son Steve, were camped in their large tent near Rock Creek. “I looked out the tent flap and saw this wall of water, rocks, trees and whatever because it was a beautiful moonlit night,” she said during a video interview in 2001 at her home in Billings, Montana. “It was just like the ground was ocean waves. And the noise you can’t believe.”

Life & Death

While the quake that formed Quake Lake, Montana, itself lasted roughly one-half of a minute, jolting awake to this earth-changing event meant life or death decisions, along with life-altering realities, within seconds. Six members of the Bennett family from Idaho, including the parents, Irene and Pud, along with their children ranging from ages five to seventeen, were heading to Yellowstone when they stayed at Rock Creek for the night.

Within seconds after the quake, wind and water caught them. In Morris’ book, as well as reports from the University of Utah Seismograph Station, the last time Irene saw her husband, he was hanging on to a sapling with his feet off the ground “like a flag” before he was ripped away. Irene said the wind was so fierce it blew their car past her and she remembers seeing one of her children being blown away. She woke up naked, pinned underneath a tree along the bank. Only she and her 16 old son, Philip, survived.

When the Greene family finally extricated themselves and their son from their tent, they attempted to leave in their station wagon, but the car was centered high on a tree. And within moments, a teenage girl ran to them saying, “You can’t leave! My mother’s lost her arm!”

Courtesy US Forest Service Northern Region.

Myrtle Painter

The mother was Myrtle Painter who was camping with her three daughters and husband, despite having an ill feeling about the trip. In his book, Morris reports how she thoroughly cleaned their house before leaving and bought additional insurance. Even traveling through Yellowstone Park, she told her husband they needed to leave “before the whole place blows up.” Unfortunately, her premonition was correct.

After her family fell asleep, Myrtle went down to the river to wash her hair, but within moments the earthquake struck engulfing her in the wind and water. When her daughter, Carole, found her, she had suffered a nearly severed arm and collapsed lung. Greene assisted Myrtle, as well as over a dozen casualties throughout the night and the next morning, to an area on higher ground called Refuge Point. Although she was transported to the hospital, Myrtle succumbed to an infection from her injuries three days later.

“As the canyon began flooding, people went to higher ground,” explained Butler. “One of these places was called Refuge Point which is a few miles west of the dam (on Hebgen Lake).”

The Lake That Tilted

When the Quake Lake, Montana, earthquake hit, fault lines tore the earth creating over a dozen scarps nearly 20 feet high, and caused multiple seiches, which is the equivalent of a tidal wave in a lake, in Hebgen Lake.

“Hebgen Lake was sloshing back and forth,” said Butler. Four feet of water topped the dam, and there was serious concern about the dam failing.

To this day, there are still cabins visible after an easy 200-yard walk along the old road roughly halfway along Hebgen Lake on Hwy 287. At this point, “The Lake That Tilted” sign tells the story of the cabins for Hilgard Lodge that were destroyed by frequent seiches. Grace Miller, who was at least 70 years old at the time and operated the lodge for years, was jarred awake by the quake and kicked open her jammed cabin door only to find a five-foot wide gap between her and the earth. She and her malamute dog made the harrowing leap as the cabin slipped into the lake.

Aftershocks

After the quake, the formerly smooth road that ran alongside Hebgen Lake and the Madison River was cracked, crumbled and non-existent in many places, with the landslide completely blocking the passage to the west. “The campers were completely trapped in the canyon,” said Butler.

Throughout the night, aftershocks reaching 5.8-6.0 in magnitude rattled the nerves of survivors. Butler said, “There was quite a bit of activity throughout the night and into the next morning. People said that they could hear the rock slides all night, which was very scary.”

At daybreak, officials were better able to assess the situation. Butler said they sent smoke jumpers to assess injuries and bring medical aid, along with finding a way to evacuate survivors. Helicopters shuttled injured victims, and Butler said there was a road crew at Gallatin Canyon that immediately mobilized their equipment and started plowing a new path. They completed it by seven that evening.

“There were tons of locals,” she said. Everyone, ranging from Air Force personnel to nearby residents, pitched in to help.

In the end, Butler said 28 people perished in total with 19 presumed buried beneath the slide, which now is the location of the Earthquake Lake Visitor Center. Memorial Boulder holds a plaque listing the names of those lost at Quake Lake, Montana.

Courtesy US Forest Service Northern Region.

Seismic Activity

Although the 1959 earthquake at Quake Lake, Montana, seems like an apocalyptic event, it’s not out of the ordinary, at least on a geological scale for this region. “The Yellowstone area in general is very active. The visitor center has a functioning seismograph to see what’s going on in real-time,” said Butler who pointed out that toward the end of March 2023, there were 200 earthquakes over two to three days. All were below 2.0 in magnitude, but it’s fairly constant activity.

“The entire U.S. is stretching,” explained Michael Poland, geophysicist and scientist-in-charge at the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory in Vancouver, WA. He said when looking at a topographical map the north-to-south ranges with valleys in between them are the consequences of the land being stretched.

“As it stretches, it breaks apart. There are faults at the base of every mountain range. That’s why you get earthquakes,” he said. “It’s not really that abnormal. It’s just the way the West is.”

Even so, he said, “(The 1959 earthquake) was the largest earthquake in the Intermountain West that we recorded.”

Poland noted that the dramatic effect on the landscape, particularly the impressive scarps, was not only because of the significant magnitude of the earthquake, but because of its shallow nature. “That is typical with a shallow earthquake. When they’re shallow enough, they make it to the surface,” he said.

Rattling Yellowstone

Even though the major impact of the incident is visible at Quake Lake, Montana, the earthquake shook Yellowstone, as well. “This area was known for the seismic activity. Even in 1871, the Hayden Expedition had a camp called “Earthquake Camp,” said Poland. Yet, since there weren’t seismic records before 1959, it’s unsure how earlier events affected the hydrothermal features over the previous centuries.

“The real effect it had was the geysers started going bananas. Hundreds that had never before erupted had recorded eruptions going off. It’s like someone grabbed the old plumbing and shook it like crazy,” he said.

Old Faithful geyser went from erupting an average of every 61.8 minutes to 67.4 minutes by the end of 1959, and today it’s closer to 93 minutes between eruptions, possibly due to the 1959 quake. According to the USGS’ Caldera Chronicles, “At least 289 springs in the geyser basins of the Firehole River had erupted as geysers; of these, 160 were springs with no previous record of eruption.”

In the Upper Geyser Basin, Seismic Geyser started as a crack in the earth’s surface, gradually progressed to a fumarole, and by the early 1960s became a small geyser that eventually developed to consistent 50-foot high eruptions.

Photo by Amy Grisak

Quake Lake, Montana, Aftershocks Today

While the initial aftershocks stoked the fears of those in the Quake Lake, Montana, area after the 1959 earthquake, Poland said, “The University of Utah suggests we are still having aftershocks today.”

In 2017-2018 over 3000 small earthquakes were recorded from the same fault line region and went in the same direction as the original earthquake. “The length of time for the aftershocks to go on is proportional to the magnitude of the earthquake,” he said.

With the seismic activity in the Yellowstone region, earthquakes, even much smaller than the one in 1959 are a concern because, as Poland noted, one of the things that is not appreciated on the hazard-human timescale is what an earthquake of that magnitude can do, particularly since there is no good way to predict them.

“What is that thing that causes them to suddenly go? We know they’re being stressed, but how do you know that moment? We know the faults, we know their history, we know what they’re capable of. We can develop seismic hazard forecasts, but cannot predict earthquakes,” he said.

This story about Quake Lake, Montana, previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story and photos by Amy Grisak.