By Bob Jones

Deep in the Central Ural Mountains of Russia are two deposits of rhodonite where solid pink to red lapidary material has been quarried since the 1790s. According to legend, before the modern discovery, the local natives noticed eagles picking up small pieces of red stone to put in their nests. The locals assumed this was for good luck, and so adopted the practice. They called the pink stone orletz, eagle stone, which is now hessonite.

Contrasting the rich red color in much of the Russian rhodonite are pleasing spidery veins and batches of black manganese oxide. They may have invaded the stone’s cracks and openings or are leftover molecules in the solution as this calcium manganese silicate rhodonite was forming.

The contrast of the pink to red silicate and black oxide adds a note of beauty to carvings and can challenge a good artist to incorporate the spiny veins into a design.

Russia’s Fondness for Rhodonite

Gertsmann collection

The Russians so highly prized rhodonite it sometimes rivaled malachite, especially for large carvings. Malachite, though found in multi-ton masses was always vuggy, and had to be sliced into smaller pieces requiring matching of its bands to achieve larger areas and patterns, such as a mosaic, to give it a solid appearance. Rhodonite, on the other hand, could be quarried in huge solid masses and large solid blocks, not unlike quarrying marble. These could be shaped and chiseled into all sorts of large solid red objects.

The discovery of two deposits at Maloe Sideinikovo and Borodulskoye in the Central Urals, not far from Ekaterinburg, now Yekaterinburg, gave rhodonite immediate recognition for its potential as a gemstone and carving stone. Today, visit any major museum, palace or cathedral in Russia, and you’ll see rhodonite used in every imaginable way along with other Russian gemstones like malachite and lapis. Because rhodonite occurs in huge solid masses, it is particularly suited for carving statues and as a massive decorative stone, even tombstones.

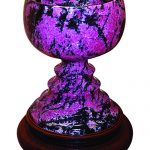

One of the finer examples of carved rhodonite is in the Hermitage, where one room has several free-standing huge bowls, tazzas, and vases. In the center of the hall is a gorgeous five-foot-high pedestal holding a nicely carved square bowl of blue lapis rivaled by an even larger carved pedestal of gray and white Kolyvan jasper holding a shallow bowl eleven feet across. This carving was so huge they had to remove a section of the wall to get it inside.

Also quite impressive is a choice example of Russian rhodonite on a four-foot-high pedestal with a six-foot diameter oval bowl laced with black spider-webbed manganese oxide. We were able to photograph such solid lapidary beauties but were not allowed cameras where the largest example or Uralian rhodonite sits.

During our excursion, we crossed the frozen Neva River and entered the famous Peter and Paul Fortress, built by Peter the Great, located directly across from the Hermitage Palace, St. Petersburg. All the czars and czarinas are entombed there within floor vaults of a royal chamber. To ensure these royals will never be disturbed placed atop each gravesite is a multiton block of shaped gemstone of Russian-dug material. The gemstones, each different from one another, include mottled gray and white Kolyvan jasper, white marble, and, most impressive, a seven-ton block of spider-webbed rhodonite, which sits on Czar Alexander’s grave.

These masses of rock were quarried long before modern mechanized equipment was available. With sheer manpower and horsepower, blocks of stone were hauled from the Urals to Saint Petersburg. I was told the Czar’s block of rhodonite weighed 55 tons when quarried. Taken to Ekaterinburg, now Yekaterinburg, it was cut to size at the royal lapidary works. From there, it was hauled to a barge by 90 horses and 50 men for transport to the Peter and Paul Fortress. This rich red-pink manganese oxide silicate gravestone is quite an impressive sight with its black spider web veining setting off the rich red rhodonite.

Russia’s more artful use of rhodonite was for huge carvings of statues and colorful stone objects. But because of its sometimes delicate pink color, it was incorporated into very delicate picturesque gem inlay work. You see it everywhere in Russia. For example, after Czar Alexander was killed with a bomb by a radical, the Cathedral of the Spilled Blood was built on the very spot he died. Inside the cathedral is an actual piece of the asphalt roadway on which his blood dropped. Over the front portal of the Cathedral of the Spilled Blood is a very colorful inlay scene featuring a variety of gemstone materials including pink rhodonite. The lovely scene is of Jesus Christ, with two attending angels.

Composition Characteristics

Rhodonite is one of those minerals that can chemically accept other elements in its structure. Elements including zinc, iron, magnesium, and calcium can replace manganese atoms in its structure. Of these, the element zinc is probably most interesting and best known to readers thanks to the now-defunct zinc mines of Franklin and Sterling Hill, New Jersey.

The Franklin deposit, which is in a metamorphosed limestone, has been the source of two other red to pink minerals with the invading elements listed above. They are the minerals bustamite and fowlerite, both varieties of rhodonite. Bustamite is a calcium manganese silicate. Fowlerite is a calcium-rich and zinc-rich manganese iron silicate. For the average collector, these pink minerals at the Franklin deposit present a challenge as they may resemble each other and rhodonite. It takes collecting experience to distinguish these red minerals from each other. The good red crystals are considered rhodonite, while the lighter colored examples are often called fowlerite. Only a chemist knows for certain.

The Franklin and Sterling Hill zinc deposits are unique, having yielded several hundred species, including at least 70 different fluorescent varieties. That the deposits are hydrothermal is no question, and they have been heavily metamorphosed in the ensuing hundreds of millions of years since forming. I believe that they may have started as black smokers.

Differing Formations in Different Deposits

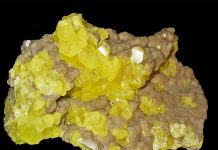

While rhodonite is spectacular as a carving and massive lapidary material, mineral

(Dr. Rob M. Lavinsky, The Arkenstone, www.arkenstone.com)

collectors prefer finely crystallized rhodonite. Some of the finest bladed rhodonite surfaced at the Huanzala mine, Huananuco Department, Peru, a few decades ago. Another much older source has been Broken Hill, New South Wales, Australia. These two sources are recognized as having produced some of the better-crystallized rhodonite specimens. They differ dramatically from each other, but both far exceed the rough, granular faced, crystallized rhodonite from Franklin.

Rhodonite forms in blocky monoclinic crystals that can be up to two inches long at the Franklin deposit, where they formed in enclosing calcite. The calcite is bound to the rhodonite and has been a problem to remove. Very few Franklin rhodonite specimens have come to light without rough granular prism faces and slightly rounded edges. One nice occurrence of Franklin rhodonite is the penchant for developing several crystals, in more or less, parallel groups or clusters, which can be quite attractive. Crystallized Franklin rhodonite is highly prized for various reasons, especially since the mines shut down about 50 years ago.

High in the Andes Mountains of Peru are the mines at Huazala, Hunanaco Department, Peru. Mineral collectors who venture to these cold and oxygen-poor climates often have a problem with high altitude sickness. When my son Bill, a water treatment specialist, visited gold mines in the Andes, he had to pass a physical before heading into these thin air reaches and was checked again upon his return to sea level.

In Peru, miners have long since adapted to the conditions found in 13,000 to 14,000 feet and higher. It is common practice for miners to chew cocoa leaves while working for the soothing effect it has dulling the discomfort they have. The rhodonite these tough miners produced is gorgeous. The color is a bright pink-red, and the crystals are best seen as lovely bladed clusters with no matrix showing. The blades can reach an inch on an edge and are tapered thin blades seldom up to an inch high. Some specimens are as much as six inches across with blades that are tightly clustered, in free-standing, almost rosette bunches. They are the finest of this type rhodonite ever mined, but few are seen today.

Rhodonite Deposits Carry Stories

An older source of superb crystallized rhodonite, the complete opposite of the bladed Peruvian specimens, are the crystals from Broken Hill, New South Wales, Australia. Here the crystals are thick, tabular, prismatic, gemmy, and deep red. They are most often found completely enveloped by silver-rich crystallized galena. Thankfully, galena suffers from complete perfect cleavage in three directions. Better yet, it did not actually fasten itself to the rhodonite crystals as calcite did at Franklin. So, the galena is easily removed, exposing the smooth-faced rhodonite crystals with a high luster, slightly rounded terminations but sharp prism faces.

The Broken Hill story is fascinating. The deposit is aptly named as it was first seen as a cluster of roughly fractured outcrops of weathered ore as if broken in some way. These outcrops later proved to be the best center of a boomerang-shaped deposit of silver, lead, and zinc ore. The “arms” of the boomerang extended into the earth to depth, and today Broken Hill is recognized as Australia’s largest and only continuously worked mine. Where else would you find a boomerang-shaped deposit, but in Australia!?

The deposit was initially discovered in 1883 by Charles Rasp, a cowboy riding the boundary of a sheep station. Luckily, he had found what we call horn silver, probably cerargyrite. His find later became the largest, most valuable silver-lead-zinc deposit in the world. He was honored in that the mineral from Broken Hill is named raspite. The halcyon days of rich mining are over, but the “line of lode”, as the major veins are named, produced some of the most gemmy red rhodonite crystals ever found. Jutting up from their galena nest, these crystals are highly prized. The crystals are never large, seldom over an inch in length, but occur in small attractive clusters. Single crystals are often slightly striated, well terminated, gemmy, and superb thumbnail size.

If you want to read an informative text on this very topic, Minerals of Broken Hill is a good reference. It can be obtained online, and I would recommend you check Rocks of Ages (http://rxofages.com). Among the authors is Howard Worner, whom I met at the Tucson Gem and Mineral Show in 1982, the same year this outstanding book was published. The reference is a bit on the more expensive side, but well worth the investment, as Howard was a mining engineer, who spent his career studying “the line of lode,” and its minerals.

While red rhodochrosite garners all the glory these days, rhodonite quietly enhances any collection. Be sure to watch for it at shows.